How Yuppies Shaped Modern-Day Boston

How the 'young urban professionals' of the 1980s created the city as we know it.

Illustration by Mark Matcho

One day a few months ago, I happened to be in the South End when I started noticing, in a way that I never have before, some of the storefronts and businesses I was passing by as I walked along a particular stretch of Tremont Street. There was the beautiful office of an über-high-end design firm. An upscale running-shoe shop. An inviting “facial spa.” A restaurant serving an intriguing combination of pizza and Middle Eastern food. A swanky doggy-care business. A dentist whose sign noted they also do Botox. It was right after I passed the wrinkle-removing dentist’s place that a thought leaped into my head:

Yuppies did this. 1980s yuppies.

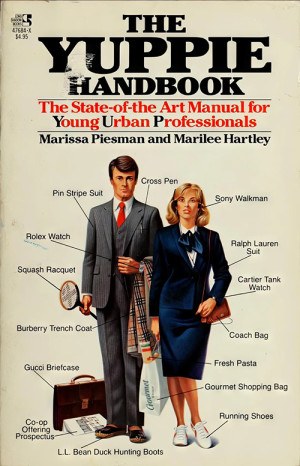

Haven’t heard that term in a while? Yeah, it’s been a minute. Yuppies, of course, were the elite, well-educated slice of the baby-boomer generation, a group of high achievers who became one of the defining cultural forces of the 1980s. The word “yuppie” was a spin on “young urban professional”—although that utilitarian phrase hardly does justice to what yuppies were all about. In fact, it was yuppies’ other characteristics that really defined them: Their preoccupation with money and career success. Their sophisticated lifestyles. Their affection for look-at-me status symbols like BMWs, Rolex watches, renovated brownstones, and memberships at upmarket health clubs.

I’ve spent the past several years writing a book about yuppies (Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation—published this month). It tells the story of who they were, where they came from, and why they mattered. My central takeaway: Despite generally being loathed by the population at large, yuppies largely created the world we live in today.

There may be no better example than Boston. The city we know now—a city of brainy, cosmopolitan people with great skin and pampered pups, but also a city of rampant gentrification, widening income inequality, and unaffordable housing—was basically born in the 1980s. And its proud parents were those Young Urban Professionals so many of us loved to hate.

The story of Boston yuppies in the 1980s actually begins in the ’70s, a decade that wasn’t the easiest for the city. For two decades, Boston had been in transition, with its industrial base thinning out and a multitude of middle- and working-class families taking flight to the suburbs. In 1950, Boston’s population was roughly 800,000. By 1970, it was less than 650,000.

But there was, it turned out, a secret weapon for pushing back against the encroaching darkness: tens of thousands of idealistic baby boomers who’d come to Boston to go to school, then made the unlikely decision to stay after they graduated. And not just stay—but actually live in the city that so many other people were abandoning. Why? For starters, it was cheap. Rents in a lot of neighborhoods were just a few hundred bucks a month, and if you wanted to buy a place, you could find something for $30,000—maybe even less. It was also convenient as hell: The new graduates were taking jobs in fields like law, finance, and marketing, so getting to their downtown offices on the T was a snap. Maybe most significantly, it all just felt cool, bohemian, and a little dangerous—the antithesis of the vanilla suburban upbringings so many of the young transplants had had.

Soon, they began trickling into various Boston neighborhoods—Beacon Hill, Dorchester, Charlestown, the Back Bay. In the working-class South End, the number of residents with a college degree jumped nearly 200 percent between 1970 and 1980. The boomer arrivistes didn’t come alone, either, but brought with them a new sophistication about how to live. Raised on TV dinners and mass-market merchandisers like Sears, they couldn’t resist palate-busting new restaurants such as Harvest (which opened in Cambridge in 1975) or the array of funky new boutiques that were opening around town. Meanwhile, in contrast to their Camel-smoking, martini-swilling parents, they were determined to be fit, flocking to the new health clubs that were also cropping up (no fewer than eight debuted in Boston between 1978 and 1982). “I’d say we were more concerned about intellectual things,” a young Back Bay resident told a representative from Boston’s Parkman Center for Urban Affairs, which hosted a conference in the late ’70s about the trend of young professionals settling down in Boston and other cities. “We want to have seen the latest films. We want to know what people are reading.” Another participant was even more blunt: “We’re more interesting,” she said, comparing herself and her fellow so-called urban pioneers with their peers in the suburbs.

It would be nearly a decade before America at large would start rolling its eyes at the smugness of what were, by then, known as yuppies, but working-class Bostonians seemed to take the measure of the new group pretty quickly. “They just don’t care about the neighborhood,” South End resident Estelle Gibeau told a Boston Globe reporter in 1981. Gibeau, who was 54, lived in a $15-a-week boarding house on Tremont Street and made ends meet with food stamps. “They’re hotty-totty, snooty. Mustn’t fraternize with the lower classes.”

Alas, the new neighbors didn’t have such warm feelings about longtime residents like Gibeau. A young South Ender who’d turned a rundown $27,000 brownstone into a showplace once featured in a magazine story listed for the Globe the types of people he saw hanging around his adopted neighborhood: “Derelict, alcoholic men, waiters in tacky restaurants and bag ladies,” he said. “They don’t really live. They just sort of come home.”

The man’s name? He wouldn’t let the Globe publish it. It seems the last time he’d been in the press—in that magazine’s interior design feature—people had thrown rocks through his window.

If you’re wondering where the word “yuppie” came from, the truth is no one really knows. The term first appeared in print in the spring of 1980 in Chicago Magazine. But when I rang up the writer who used it, veteran journalist Dan Rottenberg, he told me he hadn’t coined “yuppie”; it was just in the air around Chicago in those days.

As it happened, the Boston area would play a role in helping to popularize the word. In 1984, just as yuppies were beginning to emerge as a particular cultural type, writers Marissa Piesman and Marilee Hartley published a tongue-in-cheek paperback called The Yuppie Handbook: The State-of-the-Art Manual for Young Urban Professionals. (The book was one of many that aped the tone and format of the mega-successful Official Preppy Handbook, published in 1980.) Piesman and Hartley both lived in New York, but part of the inspiration for their book came from the three years Piesman spent going to law school at Northeastern in the mid-1970s amid a sea of young Boston professionals. It was there, she’d later remember, that she saw firsthand the priorities and obsessions of the new tribe (including their passion for exotic Szechuan food at Joyce Chen Small Eating Place on Mass. Ave. in Cambridge).

The Yuppie Handbook was a hit, but what turned yuppieness into a full-fledged phenomenon was the 1984 New Hampshire Democratic primary, in which dark horse Colorado Senator Gary Hart shocked the political establishment by beating frontrunner Walter Mondale. Hart, still in his 40s, positioned himself as a new kind of Democrat, one who envisioned a more modern American economy built not around manufacturing but around technology and other knowledge industries. Hart’s base, the media quickly concluded, was the increasingly affluent, college-educated yuppies everyone was talking about. Hart ultimately lost the nomination, but a tsunami of stories about yuppies followed, and by December, Newsweek was dubbing 1984 the “Year of the Yuppie.”

The Yuppie Handbook was a hit, but what turned yuppieness into a full-fledged phenomenon was the 1984 New Hampshire Democratic primary, in which dark horse Colorado Senator Gary Hart shocked the political establishment by beating frontrunner Walter Mondale. Hart, still in his 40s, positioned himself as a new kind of Democrat, one who envisioned a more modern American economy built not around manufacturing but around technology and other knowledge industries. Hart’s base, the media quickly concluded, was the increasingly affluent, college-educated yuppies everyone was talking about. Hart ultimately lost the nomination, but a tsunami of stories about yuppies followed, and by December, Newsweek was dubbing 1984 the “Year of the Yuppie.”

By that point, Boston itself increasingly reflected yuppie tastes, values, and lifestyles. That February, shiny, sprawling Copley Place opened—a $500 million ode to high-end consumerism with two luxury hotels, Boston’s first Neiman Marcus, and nearly 100 extravagant shops. Upscale food was showing up everywhere, including at outposts of J. Bildner & Sons, a yuppie-focused gourmet store that not only offered a fresh-pasta bar but would also deliver your dinner, along with a video of choice for your VCR. “Yuppies have enough money, but they don’t have enough time,” the store’s 30-year-old owner explained. Meanwhile, “ambition” and “achievement” were the watchwords everywhere, from the office to the gym. “It’s another embodiment of the American way of getting ahead,” the exercise physiologist at fitness hot spot Back Bay Racquet Club told the Globe. “[Club members] are not accumulating dollars in the office. They’re trying to accumulate weight plates on a Nautilus machine.” At the Women’s Athletic Club, the promotional materials described the exclusive, all-female facility as one for “socializing, exercising, and making contacts.” About 75 percent of the members, the club’s director boasted to this magazine, had not just bachelor’s degrees but graduate degrees.

It was easy to mock yuppies, but in fact, they understood better than anybody what was happening in America. In the decades after World War II, the country had seen a shared prosperity, with all income groups watching their paychecks rise equally. But the ’80s were different: An economic and cultural divide was forming between people with college degrees and people who never went past high school. In Boston, the foundation was being laid for the economy we know today, one built around finance, tech, healthcare, and higher ed. Those fields offered great paychecks for people with great credentials, but for everyone else, it was a struggle. The manufacturing jobs that had once allowed less-educated workers to join the middle class were disappearing ever more quickly, replaced by service-industry jobs that often paid far less. Meanwhile, the people who had money were driving up the cost of everything, including the cost of living. “I’m totally infatuated with the world of real estate,” a mid-twenties Bostonian told Newsweek in its “Year of the Yuppie” cover story. “It makes me feel smart, and it gives me more control over my life.” Who could blame her? She was looking at a fat $30,000 profit when she sold her Boston condo.

This past winter, a new upscale food hall opened in Boston. Or I should say another upscale food hall—the city already has at least half a dozen of them. The crowded marketplace didn’t deter Michelin-star-winning chef John Fraser from creating the Lineup—targeted at downtown office workers who want to “elevate their lunch breaks,” as one media outlet put it—inside the Winthrop Center. I stopped by for lunch one day not long after the Lineup opened, and as I enjoyed my quite delicious veggie burrito (with fried avocado and spicy salsa verde), I couldn’t help thinking about how many yuppie tastes and obsessions from 40 years ago are now mainstream. Yes, I mean the eclectic, adventurous food options Bostonians have these days, but also the scores of gyms and fitness studios that exist all over town and a luxury retail scene that includes everything from Chanel and Burberry to Dior, Tiffany & Co., and Golden Goose. You want hoity-toity, friend, you can find it in Boston.

Of course, officially, the phenomenon that gave rise to all that 1980s yuppieness came to an end on October 19, 1987, the day the stock market crashed, losing nearly 23 percent of its value in a single, terrifying session. Yuppie traders could be seen weeping inside the New York Stock Exchange, while outside, a crowd gathered, with one man screaming, “It’s all over for the yuppies! Down with MBAs!” Across America, yuppie jokes started making the rounds. (“What’s the difference between a pigeon and a yuppie? A pigeon can still make a deposit on a Porsche.”) Meanwhile, the media began proclaiming that something fundamental had shifted—the ambition and excess that yuppies had personified was coming to an end. Heading into the ’90s, America would once again be a kinder, gentler, less materialistic place.

The truth was that the broader shift yuppies had been part of over the previous decade was so entrenched that nothing was going to turn it around.

They were partly right. The word “yuppie” did start to fade from the language. And in Boston, at least some of the young professionals who’d originally gentrified city neighborhoods had, by the late ’80s, decamped for the suburbs, where their yuppie tendencies were undercut by having to drive a minivan. And yet, to paraphrase Mark Twain: Reports of the yuppies’ death were greatly exaggerated. The truth was that the broader shift yuppies had been part of over the previous decade—of a city (and country) becoming defined not by its middle class but by a well-educated elite—was so entrenched that nothing was going to turn it around. There was no putting the stain-whitening, smile-brightening yuppie toothpaste back in the tube.

Indeed, look around Boston today, 40 years after the “Year of the Yuppie,” and what you see is a place largely built by, for, and in the image of those 1980s young urban professionals. Education? Massachusetts is America’s most educated state, and Boston one of its most educated cities; one in five Bay Staters has a graduate or professional degree—nearly double the national average. The economy? Boston’s is now dominated by those knowledge industries that Gary Hart loved so much. Money? Boston has a high median income—nearly $90,000 a year—and there’s so much affluence at the top of the economic pyramid that real estate developers can’t seem to put up ultra-luxury condos fast enough.

This version of Boston is beautiful, beguiling, intoxicating—if you can afford to be part of it. The problem is most Bostonians can’t. Six years ago, the Boston Foundation’s research center, Boston Indicators, put out a well-regarded paper titled “Boston’s Booming…But for Whom?” that spelled out the extent of the area’s have/have-not problem. The report was filled with eye-opening statistics, but one set that jumped out to me was about wages. Between 1979—basically the dawn of the yuppie era—and 2017, the top 5 percent of Massachusetts residents had an inflation-adjusted wage increase of 52 percent—twice what workers in the middle saw and more than seven times what the poorest state residents got. That’s a long way from the all-boats-rising prosperity of the post-war years.

As a practical matter, we all know such inequality is most visible in the realm that ’80s yuppies were so enamored of: the ever-rising real estate market. The median home price, including condos and single-families, in the city of Boston is around $800,000, a cost that the vast majority of locals can’t come close to swinging. In fact, in a recent Redfin analysis, just 4.7 percent of listings on the market were deemed to be “affordable” to the average Bostonian.

Yet that’s the reality of the city that now exists. Of course, maybe the greatest irony of yuppie-created Boston is that even those who’ve “made it” financially still move through their days with a fair amount of anxiety. No matter how much money you have, there’s somebody down the street who has more. For the post–baby boomer generations in Boston—Gen X, millennials, Gen Z—the challenge of affording a house, supporting a family, and saving for retirement can feel Herculean. And even if you do feel comfortable, there’s the foreboding sense that your own kids will never be able to climb as high as you did, let alone higher. And so the achievement ethos yuppies embraced in the ’80s is alive and well in Boston-area high schools, with parents pushing their kids to get into the Best College Possible to even have a shot at a decent life.

The day I was walking around the South End, I found the Tremont Street building where Estelle Gibeau once lived. It’s no longer called a boarding house, of course, and some of the units inside—where Estelle once paid $15 a week—are now worth a million bucks a piece. What a difference four decades make.

As for Estelle herself, I did a Google search but couldn’t find anything more about her life or her death. What would she think of Boston now? Honestly, I think she’d be astonished by it. How could she not be? The condos. The restaurants. The shops. The money. Those snooty people weren’t much for fraternizing with the masses, but they built one hell of a town.

First published in the print edition of the June 2024 issue with the headline, “The Patron Saints of Modern-Day Boston.”