My Dad’s Last Day in Court

Watching a parent’s mind slip away from dementia is difficult in any circumstance. It’s even harder when your father is a lifelong lawyer who insists he has one final case to win.

Photo by Ethan Gulley

The earliest signs of my father’s cognitive slip dovetailed with his retirement. He’d somehow managed to keep it together for his clients until his very last day practicing personal injury law, and thankfully, none of them suffered because of his condition. When the day came for my mom and I to help Dad shutter his office on Congress Street in Boston, crating and cataloging his case files, we were both emotional. Not just because of the years of sweat equity that this mountain of paperwork represented, but also because of the faint unease we were feeling over Dad’s occasional loss of words.

We didn’t discuss this aloud that day, nor during the first year of his retirement. To do so would have made it seem real, and frankly, we weren’t ready for that. After all, while his mild tremors were expected in someone who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease some years before, his mental decline, the neurologist said, was statistically rare. What’s more, Dad functioned reasonably well that first year. He kept busy volunteering at the VA Medical Center in Jamaica Plain, where he doled out bottles of water and ambushed patients with dad jokes. His favorite: “A termite walks into a pub and asks, ‘Is the bar tender here?’” He invariably supplied his own “yuk-yuks” lest the punchline fail to land quick enough. Even when his delivery of these jokes started sounding rehearsed, as though he was clinging to a script, Mom and I told ourselves that maybe Dad’s behavioral shift was a temporary manifestation of stress triggered by his newfound retirement.

That hopeful theory was debunked after a brain specialist administered a series of tests that determined Dad’s cognitive deficit was indeed real. And while some medications could purportedly help improve acuity, there were no reliable methods of predicting his decline or halting its progression.

The full weight of this diagnosis didn’t hit me for a few days. I was in Manhattan, where I’d moved after college for a job as a financial journalist and later to pursue screenwriting. As I clacked away at my keyboard one morning, I was suddenly floored by the notion that every day would entail readjusting to Dad’s evolving new normal.

In the weeks that followed, even as my dad had many lucid days, I felt as though I was freefalling in preemptive grief and then felt guilty over my childish inability to stay strong for my dad. I started coming home to Boston a lot more often. Burned forever in my psyche are the blue abstract-patterned seat covers on the Fung Wah bus, which semi-reliably delivered me from Canal Street in Manhattan to South Station in Boston for $10 each way until the company shuttered. It was not a bad deal while it lasted.

On one of these visits, about a year after closing his office, I landed in Hull, where our family had summered for generations. Thanks to the punishing August heat wave that greeted my arrival, I slept in the cooler room with the cross-breeze. That’s where Mom shook me awake one morning. “Dad says he’s due in court today,” she said, sounding calmer than her hectic expression gave away. “He says he’s scheduled for trial, so I’m taking him into Boston. Coffee’s made.”

“Um…I’m sorry, you’re doing WHAT?” I responded. I was still groggy, but that wasn’t the only reason it took a moment to register.

“He mentioned something about this last night. I thought he was kidding. But now I’m not so sure.”

That’s the funny thing about the mercurial nature of his condition. Some days, he was credible. Other days, less so. Still, he’d been retired for more than a year—a fact I reminded Mom of as if she weren’t acutely aware.

“Well, yes, I know he’s retired, honey,” she said. “But he’s not taking ‘no’ for an answer. Look, if I don’t take him, he’ll drive himself, and I won’t let that happen, okay?”

Just then, Dad blustered in.

“Guys, let’s went!” he commanded, defaulting to one of his pet phrases.

I eyeballed the briefcase in his hand. I could tell by the way he swung it that it was empty. And in that moment, I went in for what I thought would be an easy remedial lay-up.

“Dad, I’m pretty sure you don’t have a trial today,” I asserted.

“And just how would you know that?” he challenged.

“I know because…because the courthouse called. They said your case was settled. Don’t you remember?”

I suddenly felt queasy. Did I really just try to gaslight the man who told me when I was young that all he ever expected from me was to earn good grades and tell the truth?

“Who’d you talk to? From the courthouse. I need a name!” he insisted.

“Um…Susan. Her name was Susan.”

Somehow, the specificity of that fictitious moniker tasted acrid as it rolled off my tongue. Whether or not he believed me hardly mattered.

“Oh yeah? What was her last name?” Dad asked.

I briefly considered doubling down with yet more invention. But I simply couldn’t.

“I forgot to ask,” was all I could muster.

“Let me tell you something,” he fumed. “If someone left a message for you, I’d have taken it correctly!”

And he would have, too. He was nothing if not responsible. And although he was in high dudgeon on that frantic morning, his baseline persona was that of lovable goofball. He once wore a dashiki to synagogue—just because. Mom was naturally horrified until the positive reviews came trickling in.

What else can I say about Dad? He jogged for exercise before that was even a thing. He was a virtuoso on the piano, with an uncanny ability to re-create any song after hearing it once. Festive dinner-party singalongs were a matter of course. He loved courtroom movies like My Cousin Vinny and The Verdict. But To Kill a Mockingbird was his hands-down favorite. He shared Atticus Finch’s progressive ideals but was too humble to ever compare himself to that lawyer.

Don’t get me wrong—life with Dad was not Leave It to Beaver. We bickered constantly, like it was our job. But that was mainly due to garden-variety friction between a son and his exasperatingly doting father—all the more reason I wish I exhibited more patience during the era of his decline. Then again, Mom held enough patience for us all.

“Okay,” she reassuringly said that fateful morning. “Let’s get you to court.”

Andrew, Sharon, and Leslie Bloomenthal on Newbury Street years ago. / Courtesy Andrew Bloomenthal

As the three of us barreled the minivan down Route 3A—Mom driving, Dad riding shotgun, me perched behind him—Mom and I traded uncertain glances in the rear-view mirror. Our thought bubbles screamed, Just what the holy fuck are we doing? but offered no answers. Other times, we actively stifled laughter over the sheer absurdity of the situation. I mean, it wasn’t exactly unfunny.

Somewhere in Quincy, Mom inventoried Dad’s T-shirt and denim shorts—hardly appropriate courtroom attire for the man who once donned three-piece suits and meticulously blew out his helmet of rusty red hair each morning. After veering off the road and pulling into the nearest Goodwill thrift store, it took Mom mere minutes to harvest a dress shirt, khaki pants, and a perfectly fitting size 38 Pierre Balmain blazer. At the very least, Dad looked the part as we pulled into Boston’s Moakley federal courthouse parking lot some 20 minutes later.

By then, the temperature had surged past 100 degrees outside—this during an era when such extreme weather was considered remarkable. But in that moment, our frustration was dominated by the complete lack of available parking spaces and Dad’s growing agitation with every fruitless pass around the property. Our only solution was to double park by the courthouse entrance, with one of us staying behind with the vehicle. Deciding which one of us would escort Dad inside was a no-brainer. After all, Mom had already done more than her share of heavy lifting.

Standing outside the car, I straightened Dad’s lapel. “Ready, old man?” I asked.

“Let’s do it.”

A gush of cold air welcomed us as we stepped inside the courthouse—two men without a plan. A guard instructed me to surrender my cell phone to a lady in a blue blazer behind the front desk. I opened my mouth to explain my unique need for keeping it handy before realizing how this security mandate offered me the perfect alibi to conduct some much-needed recon, away from Dad’s listening ears. After Blazer Lady deposited my phone into the beehive of cubbies behind her and handed me the corresponding chit, I asked her to check if my dad had a case that morning. Although I hadn’t any reason to expect another outcome, I was no less despondent to learn her search came up empty.

I didn’t have the heart to tell him he had no case on the docket. Not when my earlier attempt to quell his confusion went so poorly. Besides, his altered brain invented this return-to-work scenario for a reason. Leaning into his fantasy was the only humane path forward.

“So, Dad, it looks like we have some time to breathe before your trial begins,” I improvised. “Wanna peek in on another case while we wait?”

He endorsed this plan with a smile, oblivious that it was a mere stall tactic.

Our randomly chosen courtroom was packed, save for two serendipitously vacant seats, front-row center. As we slid into the pew, I immediately recognized the shackled defendant sitting just feet in front of us. This infamous murderer made national headlines a few years back and had re-entered the news cycle during his latest appeal. I had seen an item about him on TV the night before. There he was in the flesh—just one more unexpected wrinkle in an already surreal day.

Dad sat mesmerized as the killer’s attorney went to work, arguing how his client would have surely walked free had certain exculpatory evidence been allowed. I shifted my gaze to the judge. His stoic face gave away nothing, but somehow, I could tell he was cataloging every word. Watching him gave me an idea.

“Hey Dad, I gotta go take a leak,” I whispered.

“Do your thing,” he whispered back.

I found my way to an administrative office and approached the clerk behind the glass.

“Can I help you?” he said, smiling gently.

And that was it. Those four small words unleashed a deluge. Through halted breaths, I explained how my dad—a once prominent attorney—now suffers from Parkinson’s-related dementia. How the man who once frequented these halls is back on the scene for a phantom case. And how I couldn’t disabuse him of this notion—even if I tried.

The clerk nodded as I continued.

“…And so, I was wondering: Is there any way a judge can talk to him in chambers? You know—maybe give him an ‘attaboy’ for his contribution?”

After my pitch ended, the clerk sat silent for several moments—long enough for me to suddenly feel utterly humiliated. Did I really just ask this unsuspecting civil servant to broker a kumbaya moment between my dad and a federal judge—any judge’ll do?

“You know what? Scratch that,” I said before turning and walking away.

“Young man, come back here, please,” the clerk said before telling me his plan.

Back inside the courtroom, I sidled up to Dad and whispered into his ear: “Dad, come with me. Someone wants to talk to you.”

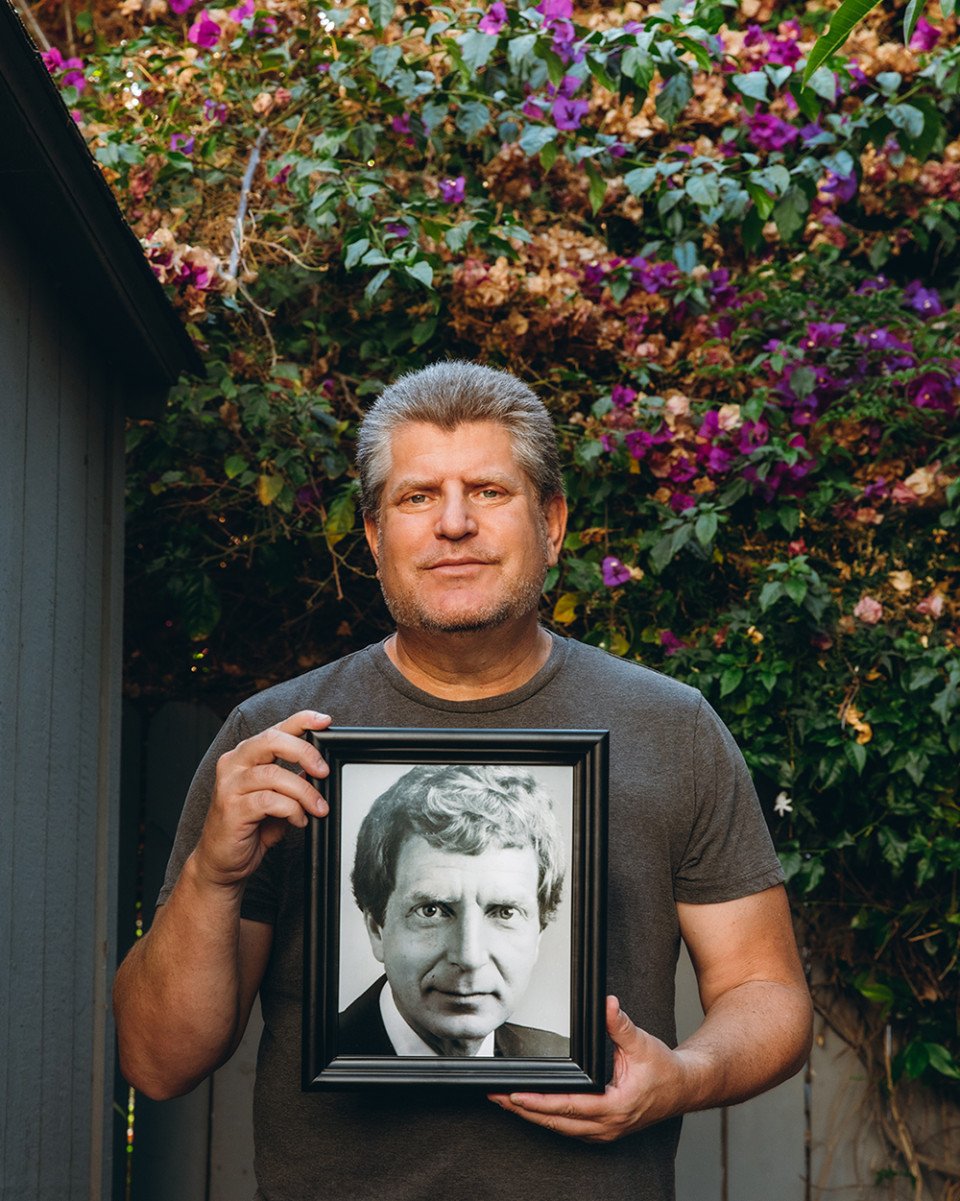

The author, holding a photo of his father. / Photo by Ethan Gulley

As I led my dad toward him, the clerk lit up, his eyes widening theatrically.

“Counsel! It’s great to see you again!” he gushed.

“And you as well!” Dad replied. Whether there was true recognition on either side of that counter was irrelevant.

“Counsel, I just wanted to tell you that today’s your lucky day.”

“Oh, really?”

“Very much. Because I just spoke to the judge. And he told me that your case has been resolved in your favor.”

“It…it has?” Dad said through a widening smile.

“Oh, yes. And His Honor also told me he’s never seen such airtight pretrial motions in his entire career on the bench!”

Dad beamed for several moments before his critical brain intervened—even then.

“Wait a minute. But what about…”

“An appeal? Can’t happen. You won. And if I may add, it’s been an honor sharing these halls with you over the years,” said the clerk without a hint of condescension. Although his patchwork legalese might not have held up to later scrutiny, at that moment, it was good enough for Dad, who extended his hand.

“The honor is mine.”

Leaning against the minivan—sweat dripping from her forehead—Mom did a bona fide double take when she saw us levitating toward her, twin smiles plastered across our faces.

“What the hell happened in there, you guys?” she asked as we got closer.

“Sharon, we won!” Dad gushed.

She looked at me, tacitly soliciting further explanation.

“Tell you later,” I volunteered. “There’s something I need to do first.”

Back inside the courthouse, I advanced to the clerk for the third time that day.

“Sir, I don’t know how I can possibly—”

“Say no more,” he interrupted. “You know, my father went through something similar. It won’t be easy, but you’ll get through it. He’s lucky to have you.”

The intervening years were indeed hard, filled with difficult decisions like seizing my dad’s car keys and his autonomy in one fell swoop. But there were also bright spots. Dad could still tickle the ivories, to name one. Even if his fingers were slightly hesitant on the piano keys, it didn’t hinder singalongs one bit. Dad also got to meet Luis, my far better half, and the two of them got on like gangbusters. Can’t put a price on that.

When Dad’s physical struggles eventually required intervention, we placed him in an assisted living facility located within walking distance from Mom’s Brookline apartment, giving her the well-earned opportunity to trade in her role as de facto caretaker for one she much preferred: loving wife. As such, she damn sure secured the coveted corner apartment at the far end of the dementia floor with a double exposure that let in more sunlight than all the other units. The revolving door of friends popping by lent even more warmth to the space. And high on the wall hung a charcoal sketch of our old house in Sudbury, positioned next to the aspirational words Mom stenciled beneath the molding. Live. Breathe. Dream. Still, the room’s focal point belonged to the engraved nameplate sitting on the coffee table—the same one that lived on Dad’s office desk for more than four decades: “Leslie Bloomenthal: Attorney at Law.”

Before my dad’s passing, he regarded his nameplate often, especially when reminiscing about the magical day he kicked butt in court one last time.

On September 5, 2015, Dad died. He was 75. But in the years before his passing, he regarded his nameplate often, especially when reminiscing about the magical day he kicked butt in court one last time. Because in his mind, it really happened. And that’s as valid as anything.

First published in the print edition of the August 2024 issue with the headline, “My Dad’s Last Day in Court.”