The Fractured, Surprising, and Sobering Truth About Kids and Smartphones

A special report on our Tiktok-scrolling, Snapchat-loving, sleep-deprived teens—and what caregivers need to know to keep kids safe.

Photo by Getty Images

So I nudged him to text his friends (nobody calls one another anymore, Mom) about going to the mall. Honestly, I would’ve driven them to Canobie Lake Park if it meant a couple of phone-free hours—anything to conjure some real-world interaction. And so there I was, idling in the parking lot with a kernel of optimism. At last, he and his friends were actually socializing in person instead of gaming virtually or exchanging pointless Snapchats from the depths of their suburban basements.

After I waited for a few minutes, four gangly boys plopped into my SUV. And in heartbreaking unison, each of them pulled out their phone, put their head down, and went silent for the 15-minute car ride home. I thought to myself: What have we done?

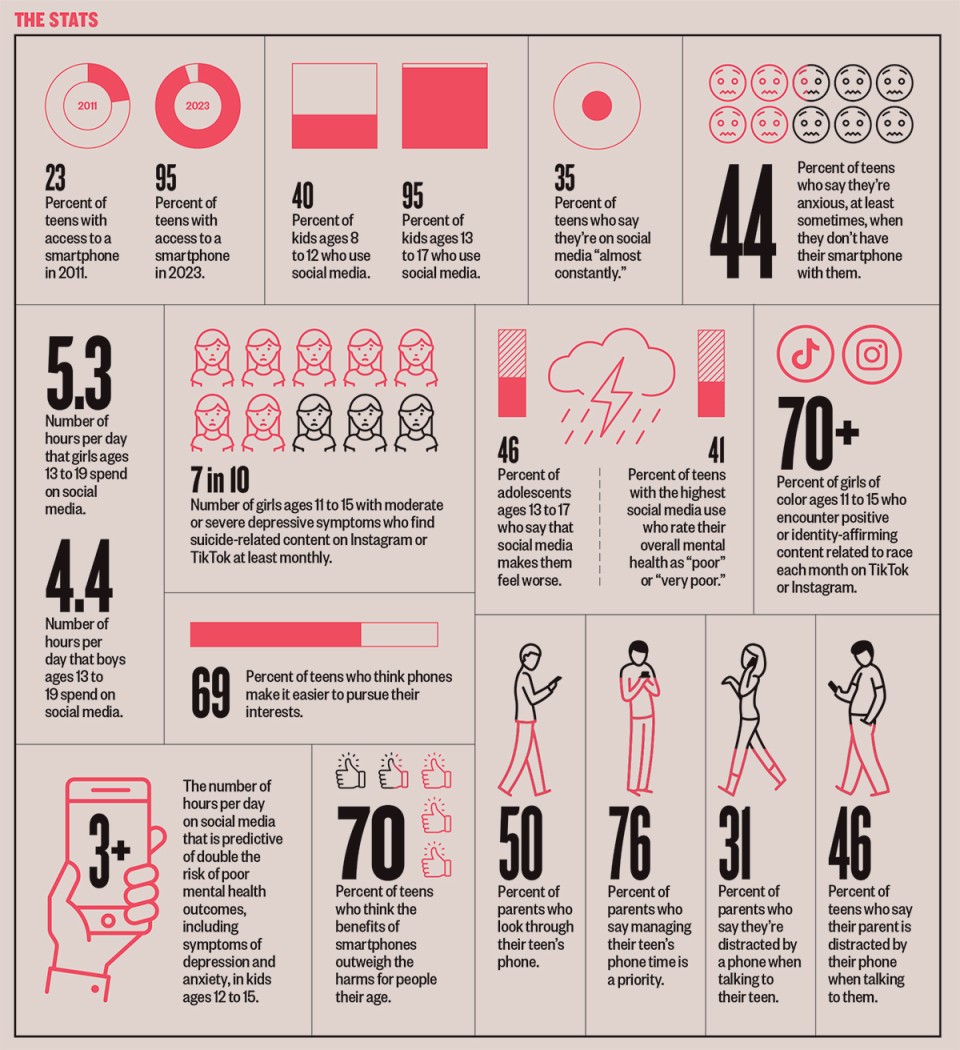

I’m hardly alone. At this point, most people believe that smartphones and social media have at least some negative effects on kids. Experts preach limits and abstinence, yet so many middle- and high-school parents (myself included) allow them: Today, up to 95 percent of young people ages 13 to 17 report using a social media platform. Nearly two-thirds of teens use these apps daily; one-third use them almost constantly, according to data from the Pew Research Center and Common Sense Media. That’s made it nearly impossible for parents who don’t want to give their child a shiny new iPhone but do want them to be part of the social flow at school and not be ostracized. Which got me wondering: What does the research actually show? Is all of this smartphone panic we’re constantly hearing about warranted, or is it overblown?

Infographic from the September 2024 issue of Boston magazine.

Are Smartphones Failing Boston’s Kids?

- How Schools Are Regulating Smartphones—Or Not

- Do You Give a Seventh Grader a Smartphone?

- Ask the Experts

- Studies Show Smartphone Use and Social Media Can Affect…

- How to Say “No” to Your Child’s Phone Use — and Stick to It

- Are Screens Good or Bad for Alternative Learners?

- How to Manage Your Teen’s Social Media

- Also, in this issue:

- The Top Public High Schools in Greater Boston, 2024-2025

Undoubtedly, there are reasons to be concerned. While reporting this story, I asked parents what worried them most about smartphones and social media. “My biggest fear is that my son will get sucked into white supremacist culture via social media, as he’s incredibly impressionable due to his mental health challenges,” said one parent. “My biggest fear is sexually explicit stuff that my kids are not ready for and are afraid to ask me about,” said another. One mom worried about online predators soliciting her children for sex. Others pointed to peer pressure writ large, which just last year caused a Worcester 14-year-old to die after he completed the viral Paqui “One Chip Challenge.”

Regardless of the content our children consume, the stats are troubling: Kids and adolescents who spend upward of three hours per day on social media face double the risk of mental health issues, including symptoms of anxiety and depression. Self-esteem also takes a hit, according to a Boston Children’s Hospital study, with 46 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 saying social media makes them feel worse about themselves. While the jury is still out on whether children predisposed to mental health problems are more drawn to social media, the link is alarming enough to make apps like Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube seem increasingly like public enemy number one. In fact, this past June, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called for a warning label on social media platforms, emphasizing that they’re associated with significant mental health harms for adolescents.

Yet if you ask local experts, there’s another lurking threat: a lack of human interaction and memory making in favor of the addictive but fleeting gratification of clicks, likes, and scrolling. These days, the currency, the common language, of childhood has changed from soul to scroll. “We lost a lot when ‘friend’ became a verb,” says Boston Children’s doctor of adolescent medicine Michael Rich, who directs the Digital Wellness Lab and the Clinic for Interactive Media and Internet Disorders.

The same is true for adults, of course, but teens are especially vulnerable to social media’s allure: Brain development, starting at ages 10 to 13 (the outset of puberty) until approximately the mid-twenties, is linked with hypersensitivity to social feedback and stimuli. In other words, teens thrive on behaviors that help them get personalized feedback, praise, or attention from peers, whereas adults have a more developed prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that helps regulate emotional responses to social rewards.

That’s part of the reason why smartphones and social media can feel even more like drugs to kids than they do to grownups, says Mass General adolescent psychologist Stuart Ablon, who recently partnered with the Your Brain on Social Media initiative to launch a free resource for families navigating conversations about social media with their kids, from privacy issues to sexting to viral video challenges. A significant issue, Ablon says, is that social media is algorithmically designed to keep kids coming back for more, and smartphones are the conduit. In his practice, Ablon sees addictive use by teenage girls, who are especially vulnerable to online social comparisons and warped beauty ideals. “Originally, [Instagram] was for sharing pictures,” he says. “But then, the algorithms were built around: ‘How can we make it enticing to get as many responses as possible and to bring people back to the app again and again to check how many likes they have?’ It’s like holding a mini slot machine in your hand.”

Photo via Getty Images

Meanwhile, ads are flooding our kids’ feeds with undesirable images and messages—like TV advertising on steroids. “We used to be concerned that when you’re watching TV, that there’d be an ad every 10 minutes,” Ablon says. “Now, there are customized ads that are popping into people’s feeds. Let’s be clear: People selling things to adolescents do not have their mental health in mind.”

In response to all of this, some local parents are joining forces with grassroots movements such as Wait Until 8th, a shareable online pledge to delay smartphone use until eighth grade. Its motto? “Let kids be kids a little longer.” The movement was crystallized in The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, by Jonathan Haidt, an instant bestseller that spurred endless parental text threads, book groups, and worrying when it came out earlier this year. In it, social psychologist Haidt makes the case that a play-based childhood has been replaced by a phone-based one, leaving organic connection, growth, and exploration in the dust.

A like-minded group in my town, Arlington Parents for Smartphone Sense, has more than 500 members on Facebook. That’s roughly the size of an elementary school: impressive, but hardly a majority in town, which makes it even harder for parents like me to just say no when it comes to the devices. After all, no one wants to see their kid completely cut off from their peers. That’s part of the reason why founder Jeff Miller, a dad of two elementary schoolers and a Wait Until 8th advocate, continues to work to build a consensus among parents. “Social media is so powerful. You look at something for two milliseconds, type in ‘get thin quick,’ and you can be drawn into things like the Corpse Bride Diet,” he says, referring to a dangerous social media trend involving a 300-calorie-a-day meal plan. He was first moved to action after watching his kids frolic on a neighborhood playground and wondering how long the innocence would last. But he’s further motivated by social media’s perniciously alluring qualities: “It’s an algorithm-driven addiction machine,” he says.

Rich, for his part, understands the damage those algorithms can inflict on kids. “Do you remember kicking a soccer ball around the backyard, taking a walk, camping with your family, or trying to cook spaghetti sauce and spilling it all over the floor?” he asks. “Those are the things that build our memories and our connectedness with each other. One of the things that I worry about is that we’ve traded away our deep, sustaining, meaningful connectedness with each other for near infinite connectivity.”

Photo via Getty Images

So what’s a concerned mom like me supposed to do? I’d already set the stage for a fight by giving my son a phone in the first place. Was he now destined for a life as a screen addict? After the mall debacle, I decided to double down on setting smartphone parameters. I installed time limits on his apps. (He’d then send a request for more time, which I found hard to deny because I was busy working or too tired to argue.) I began confiscating his phone for the day so he could spend an old-fashioned afternoon riding his bike or shooting hoops. (He’d mope and say that he couldn’t coordinate with friends without texting.) I audited his chat and messaging history while he hovered over me—but honestly, I could barely decipher what I was looking at, anyway. (For those of us over 35 or so, TikTok and Snapchat are sensory overload.) And when none of my interventions changed his usage habits, I decided I needed to dig a little deeper to see how I could navigate my son’s relationship with his smartphone in a sustainable way.

That’s when I heard something reassuring. Contrary to the doom-and-gloom narrative surrounding kids and smartphones today, several of the experts I consulted were quick to remind me that these devices are not inherently evil. In the right hands, assistive technology and educational apps used on an iPad or a smartphone can reach learners like my son, who is dyslexic. For example, to suit his learning style, he can compose a five-paragraph essay using video-based apps and talk-to-text programs on his Chromebook, or absorb a book by listening to Audible on his smartphone—something unthinkable a generation ago. Smartphones also help me track him as he’s walking home from school or text him that I’m en route to pick him up from basketball. Even social media isn’t universally detrimental: It can help kids find affinity groups, learn about current events and promote causes they care about, and flex their creative muscles.

Just like our parents taught us how to ride bikes or drive a car, we need to teach our kids how to interact as responsible digital citizens.

But just like our parents taught us how to ride bikes or drive a car, Rich says we need to teach our kids how to interact as responsible digital citizens. “It’s about helping [kids] learn to use this power tool in ways that make them stronger, healthier, and kinder to others,” he explains.

What’s more, completely banning smartphones—especially after today’s teens spent years staring at screens out of necessity during COVID—is a tall order that could end up causing parents more stress than success. “I’m a realist,” Ablon says. “And I think it’s hard to fight against it at this point. In many ways, the horse has left the barn.”

Instead of banning or confiscating phones, it’s more important to understand what our kids are seeing in their virtual worlds and engage with them about it, just as we’d engage with them about things they experience in the real world. Rich urges parents to think of what he calls the “three-plus-two Ms”: modeling behavior, mentoring, and monitoring, plus mastery and making memories.

Modeling behavior means using our phones in the ways we’d like our kids to: shutting it off during dinner and putting it down when having a conversation.

What kids are looking at online—asking questions and allowing them to show us what they’re seeing. This also plays into their sense of mastery: Instead of treating social media and smartphones as a vice, we need to reframe them as a tool with powerful capabilities that they can deploy (and shut off when needed). “If you approach it with curiosity and as a student, they will actually share—not in a reprimanding or judge-y way, but in a way of: ‘Cool, how does this work? Teach me how it works.’ They will actually share it with you,” Rich says.

Monitoring—having your kids’ usernames and passwords, just as you’d monitor their PowerSchool account or homework—is just as important. “This frankly changes their behavior. It’s like random drug testing in the workplace,” he says. And memory making, of course, is exactly what it sounds like: ensuring there’s still time to do those IRL things that define growing up.

After talking to Ablon and Rich, I began to feel a tiny bit better about my seventh-grader’s habit. Smartphones and social media are here to stay; instead of fighting them, I had to work with them, because the stakes are too high to ignore.

I began to realize that the challenge with my son wasn’t about completely banning his phone and disabling all of his apps, as much as I’d sometimes like to. It was about helping him learn and grow within his current screen-focused reality, even if it often felt uncomfortable. That meant, sometimes, letting him do nothing at all. “We make a real mistake when we just pull out our phones because we don’t know what else to do. Boredom for kids is the crucible of curiosity, creativity, and innovation, because it not only gives you the space, but it gives you that discomfort that makes you want to fill that space with something,” Rich says.

The following week, I decided to conduct a small experiment: Picking my son up from basketball, I put his phone in the front seat with me instead of letting him scroll as we sat in traffic. He stared out the window. He moped for a minute. But after a bit of awkward silence, we began talking about the sneaker-design class he wanted to take. I told him we’d research it that night at bedtime—together, on his phone. ❟

Photo by Getty Images

STUDIES SHOW

Smartphone Use and Social Media Can Affect…

ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE

A 2023 study conducted by University of Delaware and Florida State University professors of 1,459 middle-schoolers ages 11 to 15 found that academic achievement decreased as the use of Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and X increased. Kids with less frequent Facebook and Instagram use—as well as high-quality mother-adolescent communication—had better grades.

IMPULSE CONTROL

A 2023 study in JAMA Pediatrics analyzing 169 sixth and seventh graders found that habitual checking of Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat could be longitudinally associated with changes in the brain’s sensitivity to social rewards and punishments.

SLEEP

A JAMA meta-analysis found that kids’ access to and use of media devices was significantly associated with inadequate sleep quantity, poor sleep quality, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Meanwhile, 56 percent of parents of teens believe electronics, social media, and cell phones are to blame for their child’s sleep issues, according to a University of Michigan national poll.

Photo via Getty Images

Smartphones in School

How local districts are regulating smartphone use in classrooms—or not.

For students, the days of sneaking selfies in the bathroom or covertly using Snapchat during algebra may soon be over. While school districts in Greater Boston are taking different approaches to address smartphone usage, one thing is universal: It’s an issue they can’t ignore.

Some schools have stricter rules than others: In September 2023, Newton’s F.A. Day Middle School launched a cellphone-free program that requires students to drop their devices in sealed Yondr pouches when walking through the door. In January 2024, Lowell High School announced a policy requiring smartphones to be turned off and put into designated lockboxes in the classroom, though they’re still allowed at lunch.

Meanwhile, at an Arlington school, kids are told only to keep phones out of sight. Students store them in backpacks, which travel from class to class; if a teacher sees a student on their phone, they have the right to confiscate it.

Though it’s too soon for data about these programs’ successes, experts hope that schools find a way to focus on distraction-free learning while working on digital literacy—a skill as important as any other in the social media age. “The task at school is twofold,” says Boston Children’s Michael Rich. “One is didactic learning, for which smartphones are a distraction: math, science, et cetera. [But] I do think that we need to build digital literacy into our curriculum. We need to actively teach kids to use these tools.”

Kara Baskin is a contributing editor and the mother of a dyslexic middle-schooler who uses assistive devices to great advantage in school (but also spends too much time on his smartphone, according to his Mom).

First published in the print edition of the September 2024 issue with the headline, “The Fractured, Surprising, and Sobering Truth About Kids and Smartphones.”

Are Smartphones Failing Boston’s Kids?

- How Schools Are Regulating Smartphones—Or Not

- Do You Give a Seventh Grader a Smartphone?

- Ask the Experts

- Studies Show Smartphone Use and Social Media Can Affect…

- How to Say “No” to Your Child’s Phone Use — and Stick to It

- Are Screens Good or Bad for Alternative Learners?

- How to Manage Your Teen’s Social Media

- Also, in this issue: