The James Rodwell Case: A Somerville Man Fights for His Innocence

Convicted of murder on the word of a career informant, James Rodwell has spent the past 43 years trying to prove he didn't kill a Burlington police captain's son. Now he's determined to clear his name before time runs out.

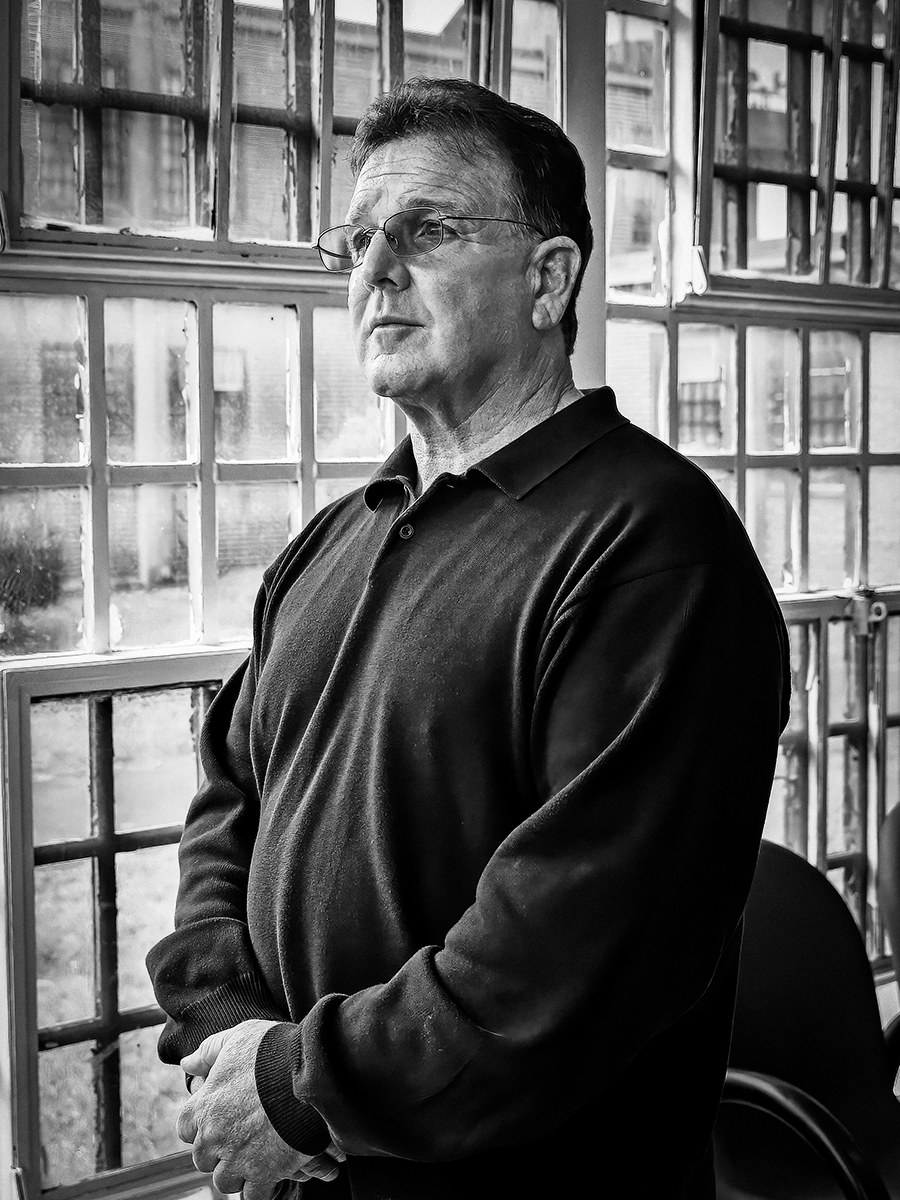

James Rodwell (pictured here inside MCI-Concord in 2017) has been trying to prove he didn’t murder Louis Rose Jr. for more than four decades. / Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The stark lamplights of East Somerville’s industrial district cast an eerie glow on the gold Buick Electra, its engine still purring in the cold December air. Inside, Louis Rose Jr. sat hunched over in the driver’s seat in a pool of blood. When police converged on the scene near the Apollo Cake Company that Sunday evening in 1978, they found shell casings on the floor and seat of the car and Rose riddled with bullets, including two in his hand and six in his head, all from a .22 caliber pistol.

The Buick was towed to the police station with Rose’s slain body still in the front seat. Forensics dusted the vehicle for fingerprints, and pathologists prepared for an autopsy. Meanwhile, police inspected Rose’s apartment, only to find that the place had been ransacked.

Rose, 21, existed within two distinctly different worlds. The son of a Burlington police captain, he’d strayed from his father’s life of law and order.

Instead, according to police reports and court records, he’d taken to peddling marijuana and cocaine as well as fencing goods. There were also whispers of his involvement with card games connected to the mafia operating out of the North End. Known as a wheeler-dealer and a savvy street kid, Rose had even taken to carrying a foot-long knife in his car after being beaten once outside of a club.

Not long after the murder, the investigation hit a wall. Police never found the alleged getaway car. Witnesses may as well have evaporated into thin air, and suspects numbered zero. As days and weeks turned into months, the case continued to stagnate. The murder weapon, much like the identity of Rose’s killer, remained frustratingly elusive. With no leads or any evidence to speak of, what had begun as a bloody execution soon entered the annals of unsolved mysteries, leaving behind only unanswered questions.

Two and a half years later, the cold case began to thaw when Frankie Holmes, a repeat offender, unexpectedly emerged. On parole after being arrested on charges of hijacking a Gillette truck en route from Rhode Island to Massachusetts, he was then arrested for violating parole and held in the Billerica House of Correction. Up against the looming threat of a prison term, Holmes put a plan in motion: He reached out to the cops and later met with State Police Detective Lieutenant Thomas Spartichino to say he’d witnessed his former boss, James Rodwell, who had owned a siding company, gun down Rose in cold blood. In exchange for immunity from prosecution, he agreed to give police a statement implicating Rodwell, potentially solving the mystery that had stumped law enforcement for years.

Rodwell himself was no choir boy. He’d been pinched for passing counterfeit cash, larceny, and possession of illegal drugs. But the talented disco dancer with a weakness for powder-blue suits had vowed to put his petty criminal past behind him. Rodwell was living in an apartment in Woburn with his father, Jack, who worked as an engineer at Raytheon and, at the time, had been separated from his wife.

Not long after Holmes’s first meeting with Spartichino at the Billerica jail, during which he fingered Rodwell for Rose’s murder, Holmes’s fortunes took a dramatic turn when he was suddenly released from prison and placed back on parole. The timing was either serendipitous or suspiciously convenient: He was freed in time to marry his girlfriend and be present for the birth of his second child, then enrolled in WITSEC, the Federal Witness Protection Program, before being arrested again a few months later.

Based on Holmes’s story, Spartichino secured a warrant for Rodwell’s arrest. When officers found Rodwell, he was at work checking IDs at the entrance of Deja Vu, a new disco tucked beside the Harbour House Hotel on the Lynnway. Dressed in a black tuxedo and bow tie, 25-year-old Rodwell had been hired for the club’s opening night in late May 1981. Outside, bright spotlights beamed across the night sky as though it was a Hollywood movie premiere while dance music echoed through the walls.

Droves of nightclubbers headed to the doors of the club, and among their ranks were three men dressed in suits. As Rodwell stood at the entrance, he remembers, the men broke through the crowd and approached him. Instead of fishing for a driver’s license, one of them took out a police badge and flashed it in front of him. It was Spartichino.

“Are you James Rodwell?” Rodwell recalls Spartichino asking.

“Yes,” Rodwell replied.

“We have a warrant for your arrest.”

“For what?”

“The murder of Louis Rose Jr.,” Rodwell says Spartichino replied.

The detective handcuffed Rodwell and led him by the collar of his tuxedo shirt into the back seat of a waiting police car. From there, they drove to Somerville police station in Union Square, where Rodwell saw Officer Thomas Macone, who knew Rodwell from the neighborhood and was shocked to learn that Rodwell was being held on a murder charge. “I told Jimmy not to get too comfortable in his cell, that it had to be some mistake,” Macone later recalled. “There was no way that he was involved in any of this. Everybody in Somerville knew Jimmy. He was a tough guy with his hands, but he was never a trigger guy. We all knew who those guys were. Jimmy was no killer.”

Rodwell was held at the jail in Billerica. Knowing he was innocent, he guessed that the whole episode was some kind of a mix-up and that he’d be back home in a matter of days. Instead, Rodwell’s arrest marked the beginning of his agonizing quest, now more than 40 years in the making, to prove his innocence.

Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The eight-day trial began in November 1981. Holmes was the first witness for the prosecution, yet despite having already given a statement to police and testifying before a grand jury in exchange for immunity, he exercised his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent. Soon, though, he was re-immunized by the judge and ordered to testify.

From the witness stand, the 23-year-old Burlington High School dropout told jurors that he met Rodwell by chance in downtown Burlington on the evening of December 3, 1978. Holmes claimed he got into Rodwell’s rented blue Ford Torino before Rodwell told him, “We’re going to rip off a dope dealer. We’re going to Woburn to pick up Louis Rose.”

Next, Holmes testified, they drove to Rodwell’s apartment, where they met a man named Anthony “Dapper” Corlito. He and Rodwell disappeared inside a room to talk, and when they returned, Rodwell was carrying a loaded .22 caliber pistol in his waistband. From there, the trio drove toward Rose’s apartment. It was around 8 p.m. when they spotted Rose’s Buick parked outside someone’s house and stopped to talk to him. After discussing a drug deal, they all drove to Rose’s home, where Rose walked inside while the others stayed in the Buick and the Torino outside. After several minutes, Holmes testified, Rodwell grew impatient and ordered Holmes to go inside and tell Rose to hurry up. But before Holmes could obey, Rose re-emerged carrying a rifle and a paper bag holding a jar of Percodan pain pills. Rose and Holmes got into the Buick, following Rodwell’s Torino down Route 93 to Mystic Avenue in Somerville. They parked behind a building and under a row of streetlights near the end of Garfield Avenue.

It was foggy and raining lightly. Rodwell’s Ford Torino sat two car lengths behind Rose’s gold Buick. Holmes testified that Rose asked him what was going on, and he got out of the Buick to check in with Rodwell. “Get in the driver’s side of the Torino and get ready to drive,” Holmes claimed Rodwell ordered him as Rodwell pulled his coat over the .22 pistol. From the Torino, Holmes said, he watched Rodwell get into the Buick with Rose. Seconds later, Holmes testified, he saw muzzle flashes as Rodwell shot Rose in the head half a dozen times. Holmes said that Rose lifted his arms in a futile attempt to protect himself from the gunshots, which echoed throughout the abandoned street, one loud pop after the other. Holmes described how the victim’s knees and legs were up in front of him and that his back was against the driver’s side door facing Rodwell, even demonstrating Rose’s defensive posture from the witness stand, which he claimed to have seen in the darkness through the rear window of the Buick on that misty night.

Rodwell then stepped out of the Buick, Holmes told the jury, and fetched Rose’s rifle and the glass jar filled with 1,000 Percodan tablets, which they intended to sell on the street (the going rate at the time, Holmes testified, was $5 apiece). According to Holmes, Rodwell got in the back seat of the Torino and told them to “get out of here.” Before they fled, though, Holmes saw the Buick—which was still running—begin to quietly roll a few yards up the street.

They drove for 15 minutes to a bridge, Holmes testified, where they pulled the car over and Rodwell and Corlito stepped outside. The men then hopped over a railing, walked down the embankment to the riverside, and tossed the murder weapon and Rose’s rifle into the dark water. According to Holmes, when he said he thought “it was crazy, that we were going to get caught because [Rose’s] father was the captain on the Burlington police force,” Rodwell told him to “shut up.” Later, Holmes testified, Rodwell reminded Holmes to “keep this to myself,” and when he saw Rodwell on later occasions, he took the opportunity to remind Holmes that if he didn’t, “I’d be dead.”

Holmes said that he’d kept mum for more than two years until he was sent to the Billerica prison for violating his parole. According to court records, he told a fellow inmate about the killing and that he wanted to unburden himself to the cops. The other inmate connected him with a state police trooper, and soon Holmes was meeting with Spartichino. In exchange for what Holmes knew about Rose, the lawman promised to put in a good word at Holmes’s upcoming parole hearing.

Under cross-examination, Rodwell’s defense attorney, William Cintolo, tore into Holmes, pointing out discrepancies between the witness’s trial testimony and what he’d originally told Spartichino in May 1981. Holmes admitted under oath that he’d failed to inform investigators—and the grand jury—that Rodwell had taken a gun from Holmes’s shared apartment with his father before the murder occurred. Then later in front of the grand jury, Holmes couldn’t specify whether the murder weapon was a .22 or .25 caliber gun.

Rodwell’s attorney then caught Holmes in the biggest discrepancy of all. He referred the witness to his original conversation with Spartichino, in which Holmes claimed that Rodwell retrieved Rose’s drugs and rifle from the trunk of his car while the Buick’s engine was still running—though he had testified in court the day before that Rodwell got out of the Buick and had the rifle and pills in his hand, with no mention of the trunk. This wasn’t his first revision of the trunk story; he had previously altered his account when speaking with Spartichino.

Addressing Holmes in front of the jury, Cintolo said, “Spartichino asked you, ‘Well, if the car was running, how did Rodwell get the keys out of the ignition, open the trunk [and] take the drugs and rifle out of the trunk to bring back to the Torino?’” Cintolo said that Holmes then changed his story, telling Spartichino that the trunk of the Buick was never opened, and Rodwell had actually put the rifle and pills in the back seat of the Ford Torino—which was also still running, trapping Holmes in the same flawed logic as his original story. In the courtroom, though, Holmes testified that he had “no idea” where the rifle and pills were stored—changing his story once again. As for the location of the murder weapon and the rifle, a team of Metropolitan Police Commission scuba divers conducted a lengthy underwater search of the Mystic River under the Wellington Bridge, where they suspected Rodwell, Holmes, and Corlito had dropped the weapons—but came up empty.

Holmes’s timeline of events on the night of the murder was also later called into question. Edward Toomey, a friend of Rose’s, told Somerville police the day after the murder that Rose had visited his apartment in Woburn on the night he was killed. They’d watched a football game on TV and then a movie on HBO before Rose left between 9 and 10 p.m., though Toomey admitted to police that he wasn’t entirely sure of the time. Holmes, on the other hand, had testified in court that Rose left his own apartment with the jar of Percodan and a rifle at approximately 8:35 p.m. What’s more, Rodwell’s father testified that he’d been home alone in his and his son’s apartment all night studying for a class and that neither Holmes nor Rodwell had stopped by—as Holmes had said—punctuating the many inconsistencies in Holmes’s testimony. (Later, Rodwell claimed, “Frankie was a disgruntled former employee of mine,” adding that Holmes was untrustworthy and he had to let him go.)

According to Massachusetts law, a defendant cannot be convicted solely on the uncorroborated word of an immunized witness. Corlito, the other man Holmes had placed at the crime scene, had been shot dead in the North End seven months after Rose’s slaying. To put Rodwell behind bars, police and prosecutors needed someone else to vouch for Holmes’s version of events.

Enter David Nagle. At 32 years old, Nagle was already a hall of famer when it came to crime. He’d faced more than 100 felony counts during the 1970s and early ’80s, nearly half of them for armed robbery. Before that, he testified at Rodwell’s trial, he’d served “almost three years” in the Marines and was honorably discharged with the rank of sergeant before turning to a life of crime. Nagle was now jailed in Greenfield on charges including five counts of armed robbery and one count of kidnapping. He met Rodwell in the prison gym while they were both at Billerica in May 1981, he said, shortly after Rodwell’s arrest for the Rose murder. “We hung together,” Nagle told the jury at Rodwell’s trial. “We were kind of tight.”

James Rodwell made an appearance at Middlesex County Superior Court this past summer in his ongoing effort to have his conviction overturned. / Photo by Matt Stone/the Boston Herald

During his time in Billerica, Nagle testified, Rodwell opened up to him about the Rose case and his involvement in the murder during their walks in the prison yard. When asked by Middlesex County Assistant District Attorney David Siegel if Rodwell specifically told him what he did in Rose’s car, Nagle replied that Rodwell said, “I put seven in his head and didn’t hesitate.” Later, Nagle said Rodwell added that he didn’t think Holmes had seen the shooting but may have heard the gunfire. Nagle testified that inmates Richard Scala and John Reeder were present for some of Rodwell’s jailhouse confessions. Most of the time, though, the two were alone when Rodwell shared details about his involvement in the crime. (Nagle also testified that he knew Holmes “fairly well” when they were inmates together at Billerica.)

At one point during the trial, Nagle told the jury that Rodwell heard Holmes had been granted immunity to testify against him and asked Nagle—again in front of Scala and Reeder—to falsely claim that Holmes was telling people, “I was involved in a murder case, and I don’t care who I blame it on, I’m going to make a deal to get out on it.” Nagle, concerned for his safety, pretended to go along with it, but said he had no intention of getting “involved in perjury in a capital case.” Nagle also told the court that Rodwell “wanted to find out where Frankie Holmes was so that he could have him whacked out.” Finally, Nagle said that Rodwell confessed to dumping the murder weapon and Rose’s rifle in a different location than the Mystic River, where Spartichino and his team already searched. Still, when Nagle told police to look in the Charles River under the North Washington Street Bridge between the North End and Charlestown, roughly 2 miles away from the crime scene, divers entered the water and again found nothing.

The assistant district attorney pressed Nagle about what, if any, promises were made by police in exchange for his testimony. Nagle replied he came forward in part so the police “could speak on my behalf on the cases I had pending against me.” He added that Spartichino made no specific promises, only that he’d advocate for Nagle by writing a letter concerning Nagle’s cases: four armed robberies in Suffolk County and two more in Middlesex.

After Nagle’s testimony, Scala and Reeder each testified that Rodwell had, in fact, never revealed to them that he murdered Rose, let alone put seven bullets in Rose’s head. They also said that Rodwell never asked them to falsify testimony against Holmes and that Nagle had studied the Rodwell case by reading newspapers.

In a surprise move, Rodwell took the witness stand in his own defense. Under oath, he admitted that he knew Holmes and Rose but had only heard about Rose’s murder from the media. Rodwell testified that he’d never owned a gun, did not see Holmes or Corlito the night Rose was killed, and was doing carpentry work for an attorney until about 6 p.m. Rodwell also said that he was not driving the Ford Torino at the time Rose died, but did admit to renting it from a dealership around that time and returning it two days after the murder. He said he did not kill Rose. As for Nagle, Rodwell said they’d met at Billerica where Nagle “asked me a lot of questions,” but that he’d never confessed or asked Nagle to perjure himself.

“So Mr. Nagle was making it up?” the prosecutor asked.

“That’s right.”

“He’s lying to this jury?”

“Exactly.”

“And when he said James Rodwell said, ‘I put seven in the kid and didn’t hesitate?’”

“He’s a liar,” Rodwell fired back. “I didn’t do the crime. Why should I discuss it with anybody?”

In the end, the nine women and three men on the jury took Holmes’s and Nagle’s word over Rodwell’s. Despite no physical evidence or fingerprints to tie Rodwell to the killing, he was convicted of first-degree murder, armed robbery, and unlawfully carry-ing a firearm and sentenced to life behind bars. The jury deliberated for only six hours. “Justice was done,” Assistant District Attorney Siegel told the Boston Globe after the verdict. “If we let a guy like this walk out on the street, he’ll just turn around and kill again.”

It was a damning statement about a man with no track record of violence. Upon hearing the verdict read aloud in court, Rodwell’s mother, Carolyn, cried out. Rodwell’s 11-year-old sister, Kimberly Pasciuto, was not at the trial but remembers feeling devastated. “I thought for sure he’d come home someday,” she says. “But he never has.”

“I thought for sure he’d come home someday,” says the sister of James Rodwell. “But he never has.”

After the trial, Rodwell was sent to the state’s maximum-security prison in Walpole. But while he adjusted to his new life on the inside, forces outside the penitentiary were kicking into gear. Several people, including a writer for Boston magazine, started to peel back the layers of the prosecution’s case. Their chief target: Nagle, the district attorney’s star witness.

As James Rodwell adjusted to life in prison, forces on the outside started to peel back the layers of the prosecution’s case.

Strahinich also unearthed Nagle’s military record and discovered that Nagle had lied under oath to the jury when he’d claimed that the U.S. Marine Corps gave him an honorable discharge. In fact, the writer learned, the military had given Nagle an undesirable discharge in 1970 after declaring him a deserter for going AWOL, including once when FBI agents hunted him down to a Charlestown apartment from which Nagle tried to escape through an upstairs window. During his elopements from the military, Nagle also developed a heroin addiction that came to define much of his life until his 2012 death from end-stage liver disease.

Nagle’s past, when brought to light, formed the portrait of a career criminal and drug addict who’d turned snitching into an elevated art. According to the Boston story, up until 1991, his rap sheet included some 116 felony charges, including 56 counts of armed robbery, four counts of assault with a dangerous weapon, and three counts of kidnapping. Yet despite the number of charges, Nagle had managed to avoid any serious prison time. The math was mind-boggling. His accumulated sentences should have kept him behind bars for between 125 and 165 years. Instead, through a series of deals struck with law enforcement, Nagle had whittled his actual time served down to fewer than eight total years. As Strahinich wrote, Nagle’s ability to trade information for leniency was so effective that Nagle

himself compared it to “having a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

While nearly all the people Nagle informed on appeared to be guilty as charged, the 1991 Boston story reported, Strahinich found one documented instance of him lying. After Nagle’s 1976 arrest for robbing a liquor store in Brighton, he falsely identified a childhood friend as his partner in crime. Soon, though, the detective on the case realized that Nagle had named the wrong person. In addition, according to inmates and defense attorneys at the time, “when Nagle had no information to give up, that didn’t stop him from faking or fabricating some in hopes of making a deal.” To get his information about a case, Nagle’s cousin Paul Courtney told Boston, Nagle often researched the local newspapers. “How did this guy get away with it for so long?” Courtney said. “I mean, he played both ends against the middle. He played everybody.”

Nagle practically admitted as much. “I fucked with [police officers and federal agents],” Nagle told Boston. “I almost—not toyed with them—but it was like a game. A high-stakes game, but it was a game.”

Even lawmen who used Nagle’s information were hard-pressed to vouch for him. John Ridlon, a retired Boston police detective, used Nagle as an informant in Charlestown during the ’70s and early ’80s. But far from endorsing Nagle’s credibility, Ridlon’s assessment was scathing. “You could see right through him,” Ridlon said to Strahinich. “Whatever [Nagle] told me, I would believe it was a lie until I checked it out. You wouldn’t just take him at his word. It’s fair to say that 97 percent of the cops I knew who knew him wouldn’t believe him unless the guy he was giving up was laying there at his feet with a gun in his hand.”

Police and prosecutors’ reliance on paid informants has always been a double-edged sword, offering crucial intelligence at the cost of potential false testimony, especially when paired with incentives that range from a good word to the judge, immunity from prosecution, or a reduced sentence. For some, the temptation to invent or exaggerate testimony can prove too tempting to resist, underscoring the risks of a system that rewards criminals for their cooperation.

In his article, Strahinich wrote that law enforcement agents and inmates sometimes compared Nagle to a California prisoner named Leslie Vernon White, who’d been profiled on 60 Minutes after admitting he’d cooked up falsified inmate confessions and then testified against the accused. Following a special prosecutor’s investigation into White and more than 100 other cases involving jailhouse informants, California became the first state to pass a so-called snitch law regulating the use of paid informants in court. Decades later, a 2005 report by the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University School of Law discovered that reliance on informant testimony was a leading cause of unjust convictions in death penalty cases, and an analysis of exonerations based on DNA evidence found that jailhouse informants had testified against the wrongfully convicted defendant in nearly one out of every five cases.

Here in Massachusetts, one of the most often mentioned miscarriages of justice involved Laurence Adams, who was convicted of killing a Boston MBTA worker in 1974 and sentenced to death, ultimately spending 30 years in prison. Like Rodwell, Adams’s conviction was based on two informants who claimed Adams had confessed to them. Years later, proof surfaced that both snitches had lied and that the prosecutors never disclosed that their informants had their criminal charges dismissed or reduced in exchange for their testimony. Adams was exonerated in 2004 and won more than $2 million from the city of Boston as the result of a civil rights lawsuit.

Unlike California and several other states, including Connecticut and Illinois, Massachusetts has not adopted regulation around incentivized informant testimony. There is currently proposed legislation on Beacon Hill, endorsed by the Boston Globe editorial board, that would mandate several key safeguards, including the creation of a statewide tracking system of cases involving informant testimony, the disclosure of an informant’s criminal history plus any special deals made to the informant, and a pretrial hearing so a judge can determine whether the proposed informant testimony is reliable before it can be heard by a jury, just as is already done for expert witnesses.

“Incentivized testimony by informants is inherently unreliable,” says Radha Natarajan, executive director of the New England Innocence Project. “Without open file discovery in criminal cases, the requirement that all communications with informants be tracked and disclosed, and reliability hearings whenever the government attempts to use this evidence, we will never truly know how many innocent people remain in prison today as a result of this evidence. However, we have good reason to question the integrity of convictions built on this evidence.”

As for Nagle, he was transferred from Billerica to the Franklin County House of Corrections in Greenfield in July 1981, not long after telling Spartichino about Rodwell’s alleged confession. The state police detective even arranged Nagle’s transportation himself. Nagle was facing a 15-to-20-year prison sentence for armed robbery at the time. After Spartichino put in a good word, as promised, Nagle was given only a 7-to-12-year sentence.

Rodwell inside the visiting area at Massachusetts Correctional Institute Concord in 2017. (Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

It’s now been 33 years since Nagle’s credibility as a witness first came into question. During that time, Rodwell has filed one formal appeal and seven motions for a new trial. The official trial file has mysteriously disappeared.

Rodwell’s attorneys have honed in on several key points, according to court documents, including that Nagle was acting as a government agent when he allegedly witnessed Rodwell’s confession, lured by promises from law enforcement, and that prosecutors withheld exculpatory evidence—Nagle’s role as an informant—at Rodwell’s original trial. The disappearance of the trial file and claims of Nagle’s perjury on the witness stand round out much of their argument. In 2015, after Rodwell’s seventh and most recent request for a new trial, Superior Court Justice Thomas Billings held a 16-day evidentiary hearing, complete with 148 exhibits and testimony from 29 witnesses. His ruling was then reviewed by Supreme Judicial Court Associate Justice Geraldine Hines.

In his 115-page decision, Billings delivered a crushing blow to Rodwell’s hopes, concluding that none of the evidence, old or new, met the legal standard for a fresh trial. He dismissed the notion that Nagle was a government agent, writing that although Nagle had expected leniency in exchange for information, “his conversations with Rodwell were not the subject of a prior agreement or promise.”

When it came to whether Nagle’s trial testimony was fabricated, Hines tackled the question head-on, writing that Rodwell had “failed to present credible evidence that any such perjury occurred, and if so, such perjury was related to a material aspect of the witness’s testimony.” The court did acknowledge that Nagle had been caught lying under oath about his military service but that it was “immaterial to…the veracity of [Nagle’s] testimony regarding the defendant’s confession.” As for the missing trial file, Hines declared that there was no exculpatory evidence contained within it and that the file was not lost because of recklessness or bad faith on the part of the prosecutor. In other words: c’est la vie.

The court’s examination of Nagle’s past also revealed a lengthy history of providing information to different law enforcement officers in exchange for favors or leniency. In the Rodwell case, Billings wrote, Spartichino fulfilled his promise to Nagle by writing a letter to the assistant district attorney on behalf of Nagle as well as speaking to the DA and a judge about Nagle. Why did the detective arrange the informant’s transfer from Billerica to Greenfield himself? It turned out, according to Billings, the prison transfer had long been in the works—since before Rodwell had even been brought to Billerica—but there were logistical delays, so Spartichino took the initiative. Still, Billings found nothing extraordinary enough to warrant a new trial for Rodwell. “It has been torturous,” Rodwell says. “All you can do is take it on the chin.”

Rodwell may be down, but he’s not necessarily out. His attorney, Veronica White, claims to have unearthed new evidence about Nagle’s work as a government informant—information allegedly withheld from Rodwell’s original defense team. White and renowned Boston defense lawyer Martin Weinberg are gearing up to present this evidence later this year in Rodwell’s eighth attempt to secure a new trial. “We are in an age where there is a widespread recognition that innocent people are incarcerated for crimes they did not commit,” Weinberg says. “The justice system needs a safeguard to protect people from the unreliable and untrustworthy testimony of criminals like Holmes and Nagle.”

In what could be viewed as a strategic pivot, Rodwell is also pursuing clemency, White says. Under Governor Maura Healey’s groundbreaking new clemency guidelines, a prisoner does not need to accept guilt to win a pardon—which suits Rodwell just fine. After all, he says, “I’m not going into the clemency hearing to apologize. If anything, I should get an apology from them.”

Now 68 years old, Rodwell counts the number of years he’s spent behind bars by the number of family milestones that he’s missed, including the births of his nieces and nephews, high school and college graduations, and wedding celebrations. After the death of his mother in 2020, only a distant Zoom call connected him to her final farewell.

Rodwell has a hint of gray at his temples, the build of a middleweight boxer softened by time, and a sharp mind. A lifer behind bars, his dreams are straightforward, almost simple. He longs to visit his parents’ graves and to celebrate with family at a restaurant in the North End. He’s lost nearly everything a person has to lose, yet he’s still holding on to hope, unbroken.

Rodwell is now locked up inside a fortress surrounded by barbed wire at the North Central Correctional Institution in Gardner, potentially his last stop. When he first went to prison, he was often tested by other inmates and survived by using his fists. Most recently, he spent his days educating young prisoners in the BRAVE unit, where he developed the curriculum, programming, and positive daily routines for fellow inmates.

Despite decades of setbacks, Rodwell remains optimistic as his family and legal team prepare for yet another battle. “We’ve all been through so much,” he says. “It will be nice to finally have a moment to celebrate together.”

First published in the print edition of the September 2024 issue with the headline, “The 11th Hour.”