Eliza Dushku’s Bold New Journey

Psychedelic therapy helped turn her life around. Now the former Hollywood actor turned certified therapist is on a trailblazing mission to do the same for others—and revolutionize trauma treatment in Boston and beyond.

Photo by Steph Larsen / Hair by Robert Ramos / Makeup by Natasha Smee / Styling by Alisa Neely

It was a bright spring day when Eliza Dushku Palandjian slid an eyeshade on and settled onto some cushions on the floor. She squeezed the hands of the two therapists gathered around her—one a trauma counselor, the other an underground psychedelic therapist—as the drugs MDMA and psilocybin started to take mind-bending effect.

Her body temperature skyrocketed, as did her anxiety. Instead of dancing in a lovely field of flowers, she was dropped hard and fast into a terrifying hellscape. Sweating and sobbing, begging for help and gripping her throat, she felt like she was dying.

While her guides gently cupped her head, reassuring her over and over that she was safe, Eliza entered an alternate reality, revisiting a decades-old trauma that she had buried deep within. The former movie and television actor had tried to numb the memory of being sexually assaulted at the age of 12, hiding it by play-acting the tough chick in leather pants on the silver screen, and suppressing it with all kinds of conscious and unconscious armor—including alcohol—in a bid to protect that scared little girl still suffering inside her.

Five months earlier, Eliza had first revealed her secret in a Facebook post, blasted out to her one million followers. Then she fell apart. “I found myself feeling so wholly unwell,” she says. “So painfully vulnerable, raw, exposed—terrified and suffering from what was diagnosed as PTSD.” Nothing could lift the darkness and terror that now lived in her body, mind, and spirit. She couldn’t sleep at night, couldn’t stop crying during the day, and she grew convinced that someone was going to hurt or kill her or her loved ones. She was lost. Alone. Hopeless. Disconnected.

About an hour into her psychedelic session, as the magic in the mushrooms and MDMA washed through her brain, she sensed a shift. A feeling “of being reborn into the world in this safe and loving way,” she says. “I finally surrendered and began to feel a release and a sense of peace and security and calm whooshing through me.” She had accessed her innate inner healer, she says, her higher self.

Over the next few hours, it was like a new version of Eliza, the real Eliza, coming back into her body. She looked out of the windows onto the green trees and heard the birds singing as if in her own voice. Gone was the darkness and terror; this new world was kind, calm, and full of wonder. It was, she says, one of the most profound experiences of her life.

The next night, Eliza slept well for the first time in six months. The terror that had once paralyzed her was now gone. She knew in that moment that she was going to make it her life’s work to “somewhere, somehow, hold that space for another, or many others,” she says.

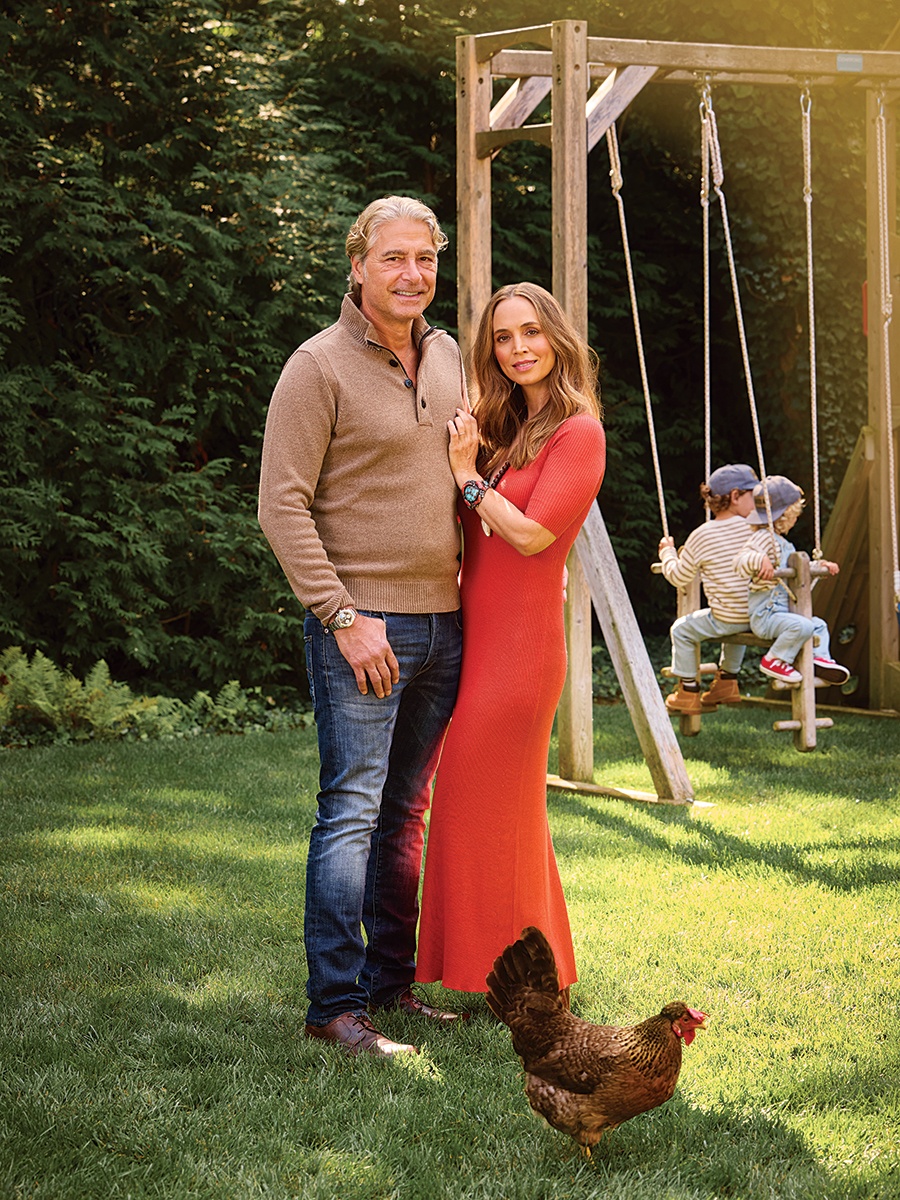

That was seven years ago, and she’s been working to make good on her word ever since. Throwing herself into her second life, Eliza is now certified in psychedelic-assisted therapy and about to complete a master’s degree in counseling and clinical mental health. Along with her husband, successful real estate developer Peter Palandjian, she’s funding research and clinical trials into the potential uses of psychedelics. The couple also funded a successful effort to get a question on the ballot in next month’s election that would legalize access to regulated therapeutic use of psychedelics.

It has been quite a plot twist that the former star—who once posed for the covers of glossy magazines and is now the mother of two littles in Cambridge—may very well be the unlikely new voice for psychedelic-assisted therapy. And it has the makings of a real-life blockbuster: Having alchemized into a healer, an activist, and a learned and engaged member of the psychedelic movement, this onscreen vampire-slaying badass wants everyone to have the same opportunity to revive and thrive that she had. “I had the means to shift directions and choose a course in my life that focused on healing myself so that I could help heal others,” Eliza says. “I would be remiss if I didn’t now share the transformation and the peace and the passion that I have. This is just absolutely so clearly my real calling, my real purpose.”

Eliza Dushku Palandjian, the former Hollywood actor, wife of a Boston developer, and mother of two young children (both pictured right) has emerged as an unlikely ambassador for psychedelic therapy. / Photo by Steph Larsen

Eliza’s long, strange trip started with an actual trip. When she was nine years old, the Watertown native stumbled and fell in Harvard Square, catching the attention of a casting director who helped her land her first acting gig in the romantic drama That Night. “Acting kind of found me,” says Eliza, a tomboy with three older brothers. The next year, she was Robert De Niro’s daughter in This Boy’s Life, and the year after that, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s kid in True Lies. Over the next 25 years, she’d go on to act in more than 30 films and star in two network series, including between 1998 and 2003 in her most famous role as the ass-kicking Faith on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its spinoff series, Angel.

A Hollywood transplant, Eliza was always a Bostonian at heart—sporting a Celtics jersey courtside at Lakers games—and could never shake the pull of her hometown, especially as both her beloved father and stepfather struggled with their health. “Every time I came back to Boston, there was just a little bit of a feeling of more authenticity,” she says. So in 2014, Eliza moved back home—living in a small apartment on the bus line in her hometown of Watertown—and first enrolled at Suffolk University, then moved to Lesley University to complete an undergraduate degree in holistic psychology. In 2016, while at her first session with a personal trainer a friend recommended, she met Peter Palandjian, a Belmont native and graduate of Harvard University and Harvard Business School. He’d been a professional, Wimbledon-playing tennis star and was now the CEO of Intercontinental Real Estate Corporation. Their relationship “took off like a rocket,” Eliza says. “It was pretty clear and instantaneous.”

Eight months after meeting, he popped the question. But before that, in March 2017, she called him while he was away on business. I just did a thing, she said. Eliza, who’d struggled with addiction as a young adult and had gotten sober eight years earlier, explained to him that she’d been at the New Hampshire Youth Summit on Opioid Awareness earlier that day as a guest of Mark Wahlberg’s brother, Jim, who was an acquaintance and fellow addict in recovery. She was not planning to speak, but after listening to former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions go on about the war on drugs and noticing the crowd practically snoozing in boredom, she impulsively took to the stage. “I’m an alcoholic,” she blurted out to the 8,000 kids and adults sitting before her. “I was a drug addict for a lot of years.” Hoping to connect with her audience, she explained that the booze was fun until it wasn’t, and detailed how she started taking drugs at the age of 14 and finally quit at 28 after her brother refused to let her be alone with her niece. Though Eliza had been sober for some time—and had helped other young women struggling to do the same—she’d never been open about it, keeping deeply personal stories of her recovery to the confines of 12-step meetings in church basements. But after going public in New Hampshire, she was horrified to wake up to headlines such as “Eliza Dushku: I Was a Drug Addict.” She worried that “everyone and their mother,” including her dream man Palandjian’s four adult children, would see her as a down-and-out druggie while standing in grocery-store checkout lines. “The clickbait was real,” she says. “It was intense.”

Peter Palandjian and Eliza Dushku Peter Palandjian in 2018. / @ELIZADUSHKU/INSTAGRAM

As the shock waned, Eliza started to wonder if perhaps her truth could be helpful to others who were struggling. And her truth was that her drinking and drugging—along with her leather-pants-wearing, tough-girl persona onscreen and off—was a way to cope with childhood trauma that she’d buried and silenced. “We’re only as sick as our secrets,” she says, throwing out one of the many 12-step aphorisms she peppers throughout conversations, sayings as trite as they are true.

That’s when she tapped out a capital “T” truth-telling Facebook post that would alter the course of her life. “When I was 12 years old, while filming True Lies, I was sexually molested by one of Hollywood’s leading stunt coordinators,” she wrote on January 18, 2018. Though it had been 25 years earlier, the details—the air conditioning blasting in the Miami hotel room, Coneheads playing on the television as the 36-year-old man rubbed against her—were right at her fingertips. “Sharing these words, finally calling my abuser out publicly by name,” she wrote, “brings the start of a new calm.”

The reality, though, was anything but calm. The 7,000 comments and 13,000 shares threw Eliza into a tailspin. “I felt like there was almost a responsibility for me to be honest about this big part of myself, and then the absolute horror the next day, realizing how vulnerable and exposed and raw and terrifying it was,” she says. “And it put me over the edge.”

Palandjian was proud of Eliza, but heartbroken watching her suffer. “Imagine you have a million followers on social media, and you share something like that,” he says. “And then within 24 hours, People magazine, the National Enquirer, New York Post, Hollywood Reporter, everyone picks it up and, man, that ain’t easy. It cast her into complete PTSD.”

Eliza tried everything to pull herself out of the dark abyss—talk therapy, trauma therapy, prescription meds, yoga and meditation—but nothing worked. That’s when the trauma therapist she was working with suggested she try a session combining psychotherapy and psychedelics. And since it wasn’t legal, her therapist suggested an underground psychedelic guide she knew in California.

After the psychedelic session, the relief from her trauma was instant, and the healing that came via future therapy was profound. Feeling safe and whole, she decided to put herself out there again after getting married to Palandjian at the Boston Public Library in August 2018. To do even more truth-telling.

On December 19, 2018, Eliza penned an op-ed in the Boston Globe revealing that her co-lead on the CBS TV show Bull had relentlessly sexually harassed her—offering to take her to his “rape van,” joking about threesomes—and then had her fired when she asked him to stop. She wrote that CBS paid her $9.5 million to settle any claim against the network, but she was required to submit to a forced arbitration with a confidentiality clause. “No judge, no jury, and no chance of finding out what really happened (or so they hoped),” she wrote.

It was a bombshell like the one she dropped on Facebook in January 2018. This time, though, she was able to stand strong after telling her truth instead of crumbling. Three years after that op-ed ran, she testified in front of the House Judiciary Committee, which voted to end forced arbitration. “It was called one of the most important labor laws of the past 100 years,” she says. “I wouldn’t have been able to do all of that without this psychedelic-assisted therapy and healing that showed me that I was safe in my body and in my life, naming and telling the truth about things. And it’s all kind of catapulted from there.”

On a February night in 2023, Eliza stood at the head of her dining room table and welcomed two dozen guests to her Cambridge home for what she and her husband billed as a fireside chat. The guest of honor was Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and a longtime crusader for the legalization of psychedelics. Also assembled was a who’s who of prominent researchers whose work here has helped make Boston an important hub of the psychedelic revolution.

At one end, dining on salad, risotto, and fish, was George Daley, Harvard Medical School’s dean. Not far away sat David Brown, president of academic medical centers at Mass General Brigham, and Franklin King, from Mass General’s Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics (CNP). Also seated was Jerry Rosenbaum, the psychiatrist in chief emeritus at Mass General, where they are studying the effects of psilocybin on rumination (the stuck thinking that seems to be central to a host of psychiatric diagnoses, from anorexia to addiction to anxiety to OCD), as well as looking at psilocybin-assisted therapy as a treatment for irritable bowel syndrome.

In all, Eliza says, it was “a dream guest list,” one that also included contributors to journals that Eliza had cited in her own graduate work and philanthropists such as Red Sox owner John Henry and his wife, Linda, co-owner and CEO of Boston Globe Media. “People think, ‘Oh, you’re an actress, and you’ve done this so many times,’” she says. “I was totally shaking in my boots.”

The Eliza Dushku Palandjian and Peter Palandjian Bridge Clinic. / Photo by Angela Rowlings

The dinner—which went off without a hitch—marked a milestone in Eliza’s seven-year journey of personal and academic growth. During that time, she earned her undergraduate degree and completed the academic requirements for a master’s in counseling and clinical mental health, with a focus on holistic and psychedelic-assisted therapies. She also obtained certification in psychedelic-assisted therapies and research from the California Institute of Integral Studies, and studied with underground teachers, learning ancient rituals and ceremonial approaches to working with energy and consciousness.

Armed with knowledge and experience as well as resources and name recognition, Eliza and her husband are spreading the word and leaning into an area of focus that remains controversial in some circles. Standing at the head of her dining table that night, Eliza did what she had done with her experiences of addiction and abuse in Hollywood: She spoke her truth, this time about psychedelics.

After dinner, everyone adjourned to the living room, where a small screen displayed a PowerPoint presentation. As they sipped coffee and nibbled on chocolates, Doblin—in his affably impassioned way—detailed his organization’s Phase 3 study on MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD. The results—which showed that two-thirds of participants who received MDMA plus therapy no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis after three such sessions—were being reviewed by FDA officials charged with deciding whether to approve the first psychedelic medicine ever. (Since then, the FDA has decided against legalizing the therapy and has asked to see the results of additional studies.) “It was just a magical kind of evening,” says Doblin, “where people were talking about their own emotional issues and how psychedelics were helpful to them at different times. It was an incredible collection of people.”

As much as the evening served to amplify the hope and promise of psychedelics and Doblin’s work, it was also a coming-out party of sorts, a night for Eliza to debut her second life as something of a public ambassador and convener for the psychedelic movement. “To see how Eliza has gotten more comfortable about being public again, I think it’s because of her healing that she’s been able to do that,” Doblin says. “In addition to [the couple’s] resources, they’re investing their reputation, and that, I think, is what’s especially admirable.”

Eliza poses with Brigham and Women’s doctors Joji Suzuki and Samata Sharma, both of whom are associated with the Eliza Dushku Palandjian and Peter Palandjian Bridge Clinic. / Photo by Steph Larsen

On a blistering day this past summer, Eliza—looking cool and chic in denim jeans and turquoise jewels, fresh off a Nantucket vacation—joined Joji Suzuki and some of his colleagues in a conference room at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where Suzuki is the director of the Division of Addiction Psychiatry. The entrance to the center in which they were convening features frosted-glass doors that proudly announce its name: The Eliza Dushku Palandjian and Peter Palandjian Bridge Clinic.

The facility, which offers traditional treatments for those with substance abuse disorders, was renamed following the couple’s $7.5 million donation to the hospital last August, a portion of which was used to support Suzuki’s research into psychedelics and addiction. “I was like, ‘Put my name on the door,’” Eliza says. Yet it wasn’t for the reasons people generally ask for naming rights after making million-dollar gifts. It was about saying, “Yes, I’m Eliza. I’m an addict. I’m in recovery. This is my story,” she explains. “It destigmatizes and reduces the shame.”

That day, Eliza sat on the edge of her seat, which was at the head of the conference table, as Suzuki updated her on his research. “I can truly say that while I have deep respect for DiCaprio and De Niro and the art they bring into the world—I’ve worked with them, and I’ve sat with Steven Spielberg—I sit here and I’m like, Isn’t this the best? ” she blurted out. “It’s so exciting to me, and it feels like something that’s moving the needle for humanity. I’m humbled, and I’m proud of this, more than anything I’ve ever done.”

Eliza and Palandjian’s backing has enabled Suzuki to explore the potential of psychedelics in treating substance abuse disorders. “We made it very clear from the very early days that if we’re going to get into this, we really want to make it front and center that we’re going to utilize psychedelics for research to target both alcohol and opioid disorders, which have been very limited so far,” Suzuki says. Right now, he has three trials in preparation for psilocybin—two to treat opioid addiction and one to treat alcoholism. At presstime, he was also seeking NIH approval to conduct a trial using ibogaine to treat opioid disorders.

The reality, Suzuki says, is that even after two decades of an ever-worsening opioid-abuse crisis, the medical world has made limited progress in developing new treatments.

The reality, Suzuki says, is that even after two decades of an ever-worsening opioid-abuse crisis, the medical world has made limited progress in developing new treatments. There is “a real recognition that we are in desperate need of innovation,” he says. “Addiction is not going away any time soon. I really believe that we need better tools, additional tools, and new tools.” Psychedelics, he says, “could potentially be a very important part of the solution.”

While Eliza and Palandjian continue to support the science, they’re also involved in the political process, hoping to clear a path for regulated access to certain psychedelic substances. In 2023, they gave $100,000 to Massachusetts for Mental Health Options, the local finance committee for a Washington, DC–based political action committee that led successful ballot initiatives in Oregon and Colorado and is spearheading the legalization charge here at home. Other big-name donors included PillPack cofounder Elliot Cohen, who donated $200,000; ButcherBox CEO Mike Salguero, who also gave $200,000; and HubSpot cofounder and chief technology officer Dharmesh Shah, who gave $600,000. The largest donor so far—$1 million—has been a California-based company that makes Dr. Bronner’s soaps. The question will be up for a vote in November. “Everyone deserves access to therapeutic, healing modalities that could change their life,” Eliza says. If the bill passes, she adds, the state can start building the infrastructure necessary for patients to access the medicine.

Still, Eliza’s commitment goes well beyond philanthropy and activism. Through her advocacy for legalizing regulated therapeutic psychedelics and by doing the hard work herself in school, she’s not just writing checks—she’s putting her very name and reputation on the line. “When people with a high profile choose to go public and sponsor a mission or really advocate for a passion, they can be a powerful voice,” says James Tulsky, chair of the department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which is overseeing the first-ever study of psilocybin on hospice patients. (Palandjian has been on the board of directors at Dana-Farber for years.) “I think that her advocacy has been hugely important,” George Daley of Harvard Medical School agrees, saying, “Celebrities carry enormous weight as influencers, and when aligned with outstanding medical institutions, can raise the profile and catalyze the research that’s essential to advancing the science.”

Eliza is approaching a pivotal moment in her journey. As she prepares for her final internship—working with veterans battling substance abuse and PTSD—and her upcoming graduation from a master’s program in May, she feels that she has finally realized her true calling. “She has found that magical intersection of passion, purpose, and talent for what she wants to do,” says her close friend Linda Henry. “She is thriving.”

In fact, when Eliza looks back on her life’s voyage so far, she thinks that maybe her long, strange trip hasn’t been so strange after all. “I just kept having these moments of thinking about where I’ve come from to where I am now,” she says. “They say in 12-step recovery programs that if you get sober, you’re going to have this life beyond your wildest dreams. And it’s true. I have these moments where I’m like, I really do.”

First published in the print edition of the October 2024 issue, also with the headline, “Eliza Dushku’s Bold New Journey.”

Related

- Massachusetts Question 4 on Psychedelics: What You Need to Know

- Inside Boston’s Psychedelic Revolution

- The Interview: Actress and Producer Eliza Dushku

- What’s the Deal with Ibogaine?