From Heartbreak to Hope: A Maine Father’s Unlikely Journey, One Year After the Lewiston Massacre

After a gunman took his son’s life in Maine’s deadliest mass shooting, Arthur Barnard found himself drowning in grief. Then his pain paved a new path. Twelve months after the massacre, the story of loss, love, and hope in Lewiston.

Arthur Barnard sits alone in his car just outside a vacant, low-slung building on the edge of the Androscoggin River in Lewiston, Maine. Not so long ago, this deserted property was a pool hall called Schemengees. Arthur has many happy memories of being here. And one memory, of a night a year ago, that changed his life forever.

Ever since then, in an act that’s part pilgrimage and part ritual, he finds himself reflexively steering his black Ford Fusion here. He’ll come to mark special occasions, or no occasion at all. Sometimes, a family member will accompany him; sometimes, he comes on his own. But the reason he comes is always the same: This is the last place he saw his eldest son, 42-year-old Artie Strout, alive.

Arthur sits here in silence with a framed photo of Artie, bearded and half smiling, resting on the back seat. This photo accompanies him everywhere, including when he comes here to speak to his son just as others might visit a gravesite. As always, his mind races with questions: Why did I suggest we come here that night? Why didn’t you leave with me? Why didn’t I hug you before I left?

On the night that prompted the questions Artie will never answer, Arthur took off from the pool hall moments before Army reservist Robert Card carried a semiautomatic rifle past a sign at the entrance that read, “No weapons or firearms allowed” and through the double glass doors, where he opened fire. In 78 seconds, he slaughtered 10 and injured 10 more, following his earlier rampage 4 miles away that left eight dead and three wounded. It was the 10th-deadliest mass shooting in modern American history and the deadliest mass shooting ever in Maine, a famously gun-friendly place where residents routinely hunt for sustenance and sport. The state’s gun laws are considered among the more lenient in the country—receiving a D minus from the Giffords Law Center’s Annual Gun Law Scorecard—and until that night, many voters and politicians on both sides of the political aisle saw little reason for anything to change.

Arthur had never given much thought to Maine’s gun laws or politics. In the aftermath of the shooting, though, a new set of questions consumed the 63-year-old father of seven and grandfather of 20, who became the only victim’s family member to speak out for gun law reform in a state grappling with its stance on firearms. He challenged everything—private sale loopholes, the legality of semiautomatic rifles, you name it. It gnawed at him how Maine had gotten sloppy with its gun laws. How the state required registration for cars but not for all firearms. It didn’t make sense.

Arthur has always believed that people who have close calls with death survive for a purpose. He left that pool hall moments before the shooter arrived, and because of that, he is alive today—and he thinks he knows the reason. “I have to do gun safety advocacy all day,” he says. “I don’t know anything else to do.”

Arthur Barnard left that pool hall moments before the shooter arrived, and because of that, he is alive today—and he thinks he knows the reason. “I have to do gun safety advocacy all day,” he says. “I don’t know anything else to do.”

It was still light out on October 25, 2023, when Arthur drove to Artie’s home in Auburn to collect his son before heading to Lewiston, just 10 minutes away. They passed the Y, a Hilton hotel, a novelty shop, and the turnoff to Arthur’s daughter’s house, talking the whole way about their favorite subject: their kids.

Of all the things Arthur loved about his son, and there were many, Artie’s devotion as a father stood out—not only to his own children but also to those of his wife, Kristy, whom he embraced as if they were his own. “He was strict when he needed to be,” Arthur says. “But he always made life fun for them.”

Following in the footsteps of his dad, a strong pool player who decades earlier had played in a local league, Artie also loved to shoot pool—so much so that in 2023, he joined a team for the first time, practicing with his teammates at Schemengees, a local gathering spot and pool hall with the slogan: “Come for the Great Food, Stay for the Good Times, Cheers.” He set his heart on doing well enough in the Maine league that his team could attend a national tournament in Las Vegas set for May 2024. Artie had never been on a plane, never been farther from home than Boston, but it was his goal to go.

As they passed under the metal carapace of the bridge that took them over the river to Lewiston, their conversation focused on where to play pool that night.

“Let’s go to the 20M club,” Artie suggested, referring to a private pool club off to the left.

“Why don’t we go to Schemengees instead?” Arthur suggested, knowing Artie’s team practiced there and that his son might see his fellow teammates. There was another reason Arthur wanted to go there: He was on the hunt for a pool claw—a specialized cue rest that he suspected the hall would carry. So they turned right, driving past the back side of the first-floor apartment that they’d shared when Artie was a boy before pulling into Schemengees’ parking lot.

Inside, the bar area was packed; a cornhole tournament was in full swing in the back, while near the entrance, Maxx Hathaway, who was on another team in Artie’s league, played on the only occupied pool table. Arthur and Artie greeted Joey Walker, the bar manager, who served as an alternate for another team in the league. He told Arthur he didn’t have any claws for sale but offered up one that someone had left behind and never claimed. Arthur and Artie ordered sodas—neither of them drank alcohol—and started playing at the second table from the door.

Before long, one of Artie’s teammates, 23-year-old Justin Karcher—who was also a friend of Artie’s oldest son, Marcus—arrived to join them. In his quest to improve his game, Karcher took every opportunity he could to play Arthur, who was the better player. Both Karcher and Artie joked that maybe they should kick someone off their team so Arthur could take his place.

At close to 7 p.m., Arthur announced that it was time for him to head home.

“That’s fine, Dad,” Artie replied.

“You know bonehead, you gotta leave with me,” Arthur said. “We left your car at home, remember?”

“I want to stay and play with Justin a little more,” Artie said, adding that his wife could pick him up later. Nodding, Arthur placed his pool stick and new pool claw into his case and said goodbye to his son.

“I love you,” he told Artie before heading to the door.

“I love you, too, Dad,” Artie replied.

Neither of them had any idea that just minutes earlier, 40-year-old Card had walked into a nearby bowling alley carrying a semiautomatic rifle with a scope and laser targeting system and opened fire, killing eight people and injuring three in just 45 seconds. Within minutes, police cars and ambulances, sirens blaring and lights flashing, swarmed the parking lot. By then, though, the shooter was already driving south, cutting silently through the darkness toward his next target barely 4 miles away.

Arthur and his son Artie loved playing pool together, and played the night he died. / Photo by Fatih Aktas/Anadolu

Some father-son relationships are constructed around the dinner table. Arthur’s relationship with his son was largely built around the pool table.Artie’s parents—who never married—split up when Artie was four. Even though his mother went on to change her son’s last name to Strout to match her own, nothing could break the bond Artie had with his father. When Artie was 10, his mother told Arthur she was having a hard time controlling his combative behavior, so Artie joined his father in a ground-floor apartment in the rough-and-tumble Lewiston neighborhood of Little Canada, named for the immigrants who worked in the textile mills that had made Lewiston the richest city in the state before their closures immiserated it. Today, despite being home to Bates College, Lewiston is the poorest city in Maine.

Between parting ways with Artie’s mom and reuniting with his son, Arthur’s life had changed significantly. He was working at one of Lewiston’s last remaining mills when he was sentenced to five years in prison for selling one ounce of cocaine to an undercover police officer. (Consequently, he is barred from legally acquiring firearms.) He only served 16 months, and eventually secured a job as a dishwasher at a fine-dining restaurant in Lewiston. He quickly moved up to become a line cook, working side-by-side with a former Culinary Institute of America instructor who taught Arthur the art of French cooking. (Arthur would eventually become the head chef there.) He also had five of the six more children he’d go on to have, got married, and then separated from his spouse.

When Artie moved in with his dad, Arthur couldn’t afford a car, so he walked everywhere, often tossing his skinny son atop his shoulders and carrying the boy wherever he went. Arthur’s apartment was modest, and his earnings were meager, but he did have money for one thing: a pool table, which he put smack in the middle of the kitchen. Arthur never forgot the first time his son laid eyes on it. “Artie seen the table and, well, you know kids with balls,” he says. “He lit right up.”

At the time, Lewiston had the largest pool community in the state, with three pool halls and several private clubs. Arthur was a formidable player; when he played for money, he could win as much as $1,600 a week. Now he was about to add pool teacher to his résumé. “Artie wanted to play all the time,” Arthur recalls. “Pool is like geometry. I says, ‘This is just like math.’ So I’d set him up with a straight shot, then I’d give him little angles, tiny angles, and when he got that, I give him a little more angle until he understood what he had to do. He was a fast learner.”

Meanwhile, as Artie grew older and fell deeper into pool, Arthur found himself with less time to dedicate to the game that once occupied so much of his own time. After raising his older children to adulthood, he embarked on a new chapter of parenthood. In 2011, he stepped in to adopt two of his grandchildren—ages five and eight—from his second son, who was using drugs, to keep them out of foster care. Soon after, he learned that two children of another son, who were three and four years old, were headed for foster care because their parents were also abusing drugs. Arthur told the caseworkers he wanted to adopt them, too. “The guardian ad litem looked me right in the eye and said, ‘No judge in the world is ever going to give you four grandchildren. You’re out of your mind.’ I said, ‘Really?’ and I went to court and got them.” It took 10 months to gain custody of the grandkids, and three of the four are still living with him today. “I have been raising kids my entire life,” he says. “I’m the oldest and ugliest single mother in Maine.”

Even before his house overflowed with grandchildren—who affectionally call him Bumpa—Arthur had taken in his ex-wife’s autistic adult cousin when he had nowhere else to go. It was a full house, and when the kids grew older, Arthur moved his bed into the living room so everyone under his care could have their own room.

In 2022, Arthur’s household grew even more when he took in another addition: the pregnant mother of two of his adopted grandchildren, who soon after gave birth to Leland—the grandchildren’s half-brother. Though he is not biologically related to Arthur, he considers the child his grandson. Leland’s mother sleeps on the couch, and Leland in a crib, just a few feet from the foot of Arthur’s bed.

Despite his busy schedule with work and grandchildren, Arthur always made time for Artie. But when his son called on the afternoon of October 25 suggesting a few games of pool, Arthur hesitated. He had a 5:30 a.m. shift for his job as a cook at the Holiday Inn in Portland the next day. He knew their pool sessions tended to stretch on—there was always just one more game—but he couldn’t resist spending time with Artie. “Heck, why not,” he said. “Let’s go shoot a few games.”

Photo by Fatih Aktas/Anadolu

After the shooting, Lewiston went into lockdown while a manhunt for the shooter was underway. / Photo by Fatih Aktas/Anadolu

Looking back, that decision would change the course of Arthur’s life forever. Not long after he left the pool hall to go home, Card stepped out of his car in the Schemengees parking lot, leaving the motor running, and walked into the building with his weapon, black, slender, and heavy, gripped in both hands. When Karcher, Artie’s friend and teammate, turned to see the gunman in the doorway, his eyes dropped to take in the man’s rifle, which was pointed straight at him. Then his gaze lifted to meet Card’s emotionless stare. From right behind him, Artie shouted: “He has a gun!”

In an instant, Karcher found himself sprawled on the ground. He tried to stand up, but his body refused. Only then did he realize he’d been shot. Artie, meanwhile, who’d been standing right behind him, was now lying on the floor just an arm’s length away.

The bar manager, Joey Walker, lunged at the gunman with a butcher’s knife. But before he could reach the killer, shots rang out, sending Walker to the floor. Card pressed deeper into the pool hall, mowing people down in his path. As the last round left his magazine, he swiftly ejected it, the empty clip falling to the ground. In that brief moment, panicked patrons desperately dashed for the exit. But Card quickly slammed a fresh magazine into his weapon and opened fire as they fled.

In the back, the cornhole players scattered for cover. One darted into a utility room, then peered out cautiously—only to lock eyes with his teenage son, who was only partially hidden behind a wall in the main room. Card came face-to-face with the teen right at the moment his father spotted a circuit breaker. He bolted forward, yanking the switch and plunging the pool hall into darkness as his son darted across the room and leaped into his lap.

In the blackness, all anyone could see was the green dot of Card’s laser sight moving across the room as he continued to pick off targets. Then the gunman paused, as though he were weighing his options, before exiting the building, getting inside his car, and driving away. (A day and a half later, he took his own life). Card spent just 78 seconds inside the building, during which time he murdered 10 people and injured another 10—one person for every 3.9 seconds he was there.

As chaos erupted, customers both inside and outside the pool hall desperately called 911 for help. “Get to fucking Schemengees’ Bar and Grille now, there’s a shooter,” one caller pleaded. Another person, crouched and hiding under a pool table, spoke into his smartwatch, telling the dispatcher that he was okay but that someone next to him had been shot and needed help.

Flowers were left on the wall outside the Central Maine Medical Center, where victims were transported after the shooting. / Photo by John Tlumacki/the Boston Globe via Getty Images

Sirens pierced the night air outside the pool hall some five minutes after the first 911 call, but for Karcher, bleeding on the ground next to Artie, it felt like an eternity. The shooting at the bowling alley had stretched emergency services thin. With victims fighting for survival at Schemengees, there was no time to wait. Police seized the moment and loaded the wounded into their cruisers to rush them to the hospital. Karcher, already slipping into unconsciousness, was the second person carried out of the pool hall and ferried to the Central Maine Medical Center at top speed.Arthur had only made it one mile from Schemengees on his way home when his ex-wife, with whom he is still close, called his cell phone. She knew he had been there with his son Artie and was panicked.

“There’s a shooter at Schemengees,” she blurted out.

“No, you must be talking about Legends,” he replied, not believing that something could have happened at the pool hall he left just minutes earlier.

She told him she would double check and hung up. When Arthur saw her name flash across his phone again a moment later, he pulled into the parking lot of Governor’s Restaurant & Bakery and answered the call.

“It was Schemengees,” she said.

Instantly, Arthur knew his son was gone. Given that Artie and Karcher were playing pool some 20 feet from the front door, he couldn’t imagine that either of them had survived. Arthur drove to the hospital, where he found other victims’ families waiting. After a few hours, medical staff took each family aside, one by one, to share the information they’d been anxiously awaiting.

Maxx Hathaway, who was playing pool one table away from Artie and his dad, was dead. So was Joey Walker. Karcher was in surgery as doctors worked to save his life after seven bullets shattered his right shoulder, grazed his left, and pierced his lung, kidney, and liver. Doctors would need to place him into a medically induced coma and on a ventilator. It was too early to know if he would live.

As it turned out, lightning had struck twice, leaving Karcher’s family reeling. Four years earlier, Karcher was sitting in the car in a Walmart parking lot when someone got into an argument with his father and gunned down his dad one row of cars away. Now, in a cruel twist of fate, Karcher himself lay critically wounded by gunfire.

At first, emergency room staff said that Artie was at the hospital. Then, at 11:30 p.m., they said they’d made a mistake. Like more than half the people who were shot that night, Artie never made it to the emergency room. He had died on the pool-hall floor.

Arthur was shattered, drowning in grief and disbelief. Yet as dawn broke the following day, a quiet determination began to take root within him—a promise to prevent something like this from ever happening again. “I don’t know what I am going to do,” Arthur says he told people at the time, “but I know I am going to do something. I have to. I can’t just go back to my life like nothing happened.”

President Biden visited Lewiston, meeting with the families of the victims, including Artie’s. / Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP

On a Sunday morning 11 days after the shooting, some 200 people solemnly filed into the Pinette Dillingham & Lynch Funeral Home in Lewiston, where photos of Artie lined the wall and the gritty, soulful sounds of “Simple Man” by Lynyrd Skynyrd filled the room. On a table at the front, sitting in front of two crossed pool sticks, sat a black urn filled with Artie’s ashes. (“No one should view his body,” Arthur says someone from the funeral home told him when Artie’s remains arrived there.) After the service, friends and family drove to Legend’s pool hall, where they played in Artie’s honor. Karcher was noticeably absent; he was still at the hospital fighting for his life.

About a week after the funeral, Arthur began regularly visiting the Maine Resiliency Center in central Lewiston. The facility, housed in a building that was once an L.L. Bean call center, was established in November to support victims of gun violence. Arthur went often on his quest to meet everyone touched by the tragedy and seek solace among those who understood what he was going through.

One evening, right before the center closed for the night, Arthur stopped in to ask a question that had been nagging him: Was there an organization that united or supported families affected by mass shootings across the country? Two Red Cross workers seated by a wood-paneled hearth suggested Arthur contact Fred Guttenberg, a former entrepreneur from Florida who had become a full-time activist against gun violence after losing his 14-year-old daughter, Jaime, in the Parkland school shooting. Arthur messaged Guttenberg on Facebook that same night.

When the two men spoke on the phone the next day, Arthur needed advice. He asked how he was supposed to balance his grief with his obligations to take care of his family and still manage to work and pay the bills. He wanted to know how to hold his life together—and still find a way to dedicate himself to advocacy. “He had already, in his mind, decided that he just can’t sit still, but that he had to say his part,” Guttenberg recalls.

A week later, Arthur penned a handwritten letter to Maine Governor Janet Mills. In neat and elegant cursive, he explained that his son had been killed in the massacre and asked if he could be part of the recently formed Independent Commission to Investigate the Facts of the Tragedy in Lewiston. He hoped to give a victim’s family perspective. “I am still coping and grieving like everyone else from this day, but this letter is part of me and my process of moving forward,” he wrote. “I know in my heart that somehow, I have to find a way to try to make a difference. Not only for my son, but for all the families that have gone through this before and are going through this horrible grief right now.”

Two days later, it was Thanksgiving, the first of many holidays without Artie. After dinner, Arthur packed up leftovers to give to Karcher, who was still in the ICU and had just been cleared to eat solid food, as well as his nurses. Arthur hadn’t seen Karcher since the night of the shooting. Up until then, he’d purposefully stayed away, scared of triggering Karcher by showing up at his bedside.

Arthur entered Karcher’s room and approached his son and grandson’s friend. Karcher still couldn’t move his right arm but had some mobility in his left. Gently, Arthur took Karcher’s left hand.

“I’m so happy you left when you did,” Karcher said.

“I’m so happy you made it, man,” Arthur replied. “I’m so happy you are here.”

Karcher confided that he feared his pool-playing days were over—not because of his injuries, but because he doubted that he’d ever be mentally ready to return to the game. Arthur looked him in the eyes. “Don’t let a guy like that take away the things you love,” he said. “If you have something you love, keep doing it. Just because this happened, you don’t have to lose that.”

“Artie would have said the same thing,” Karcher replied.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Karcher, Arthur had recently spoken to the head of their pool league and arranged to take Artie’s place on the team, just like they had joked about the night of the shooting. He was determined to do everything he could to help them make it to the national tournament in Vegas.

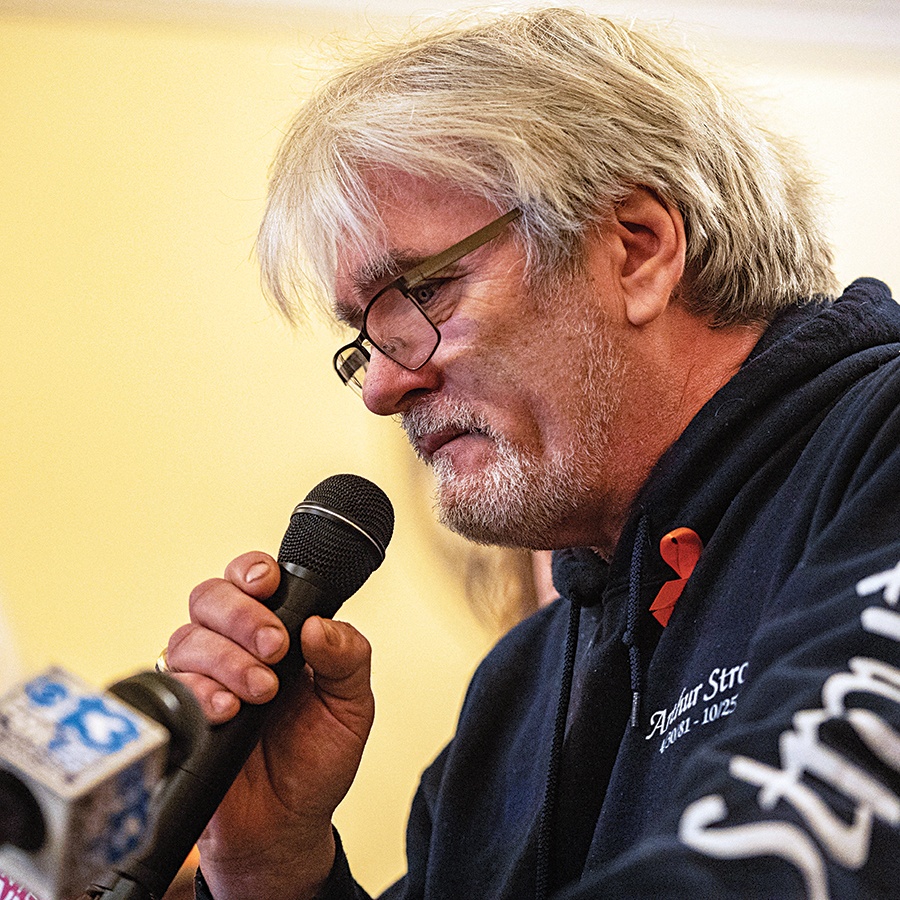

Arthur Barnard found his purpose—advocating for gun law reform—after losing his son in the Lewiston mass shooting. / Photo by Tony Luong

Just four days after the mass shooting, thousands gathered for a vigil in Lewiston. / Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Arthur’s return to work was far from smooth. One morning, before setting out to the Holiday Inn in Portland for the breakfast shift, he pulled into the Dunkin’ near his home to pick up a coffee for the drive. He never made it out of the parking lot. Instead, he sat in his car, screaming and crying for hours. “I’m surprised no one called the police on me,” he said. But that was just the beginning. In the weeks that followed, his half-hour commute home from work often stretched twice as long because he had to pull over to grieve.

In early December, Arthur got on a plane for the first time in his life. Guttenberg’s organization had paid for him to travel to the eleventh annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence, which took place at the venerable St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Washington, DC. One by one, people rose before the crowded chapel and spoke. When it was Arthur’s turn, he walked quietly to the front of the chapel holding a photo of Artie. “This is my son Arthur Strout,” he said. “He was killed five weeks ago.”

There was an audible, collective gasp in the room, but Arthur, lost in his own emotions, failed to hear it. When he returned to his seat, an overwhelming tide of feelings washed over him, and he needed to get some fresh air outside. As Arthur put on his jacket in the chapel’s hallway, a man walked through the double doors and straight up to him. The man, it turned out, was a father who had lost a child the year before in the Uvalde, Texas, school shooting. And like Arthur, he had vowed to ensure these kinds of gun tragedies would never happen again.

“I feel like I failed you,” he told Arthur, weeping.

“You didn’t fail me,” Arthur assured him. “Our systems failed us.”

While in Washington, Arthur received a crash course in American politics. He visited the White House, where he spoke to Vice President Kamala Harris’s task force on gun violence, and then the U.S. Capitol, where he spoke to members of the Maine delegation and watched as senators debated gun safety measures.

At the vigil in DC, Arthur also met Judi Richardson, a Maine woman whose daughter was slain by a gunman years ago and sat on the board of the Maine Gun Safety Coalition. Several weeks after they both returned home, she called and offered him his first speaking opportunity: On January 3, the Maine legislature would be convening for the first legislative session since the mass shooting, and people would be showing up to support several pieces of legislation—including background checks for private gun sales, a ban on bump stocks, and a red-flag law. The organization hoped someone affected by the Lewiston shooting would speak, and she had immediately thought of Arthur.

Since the shooting, Arthur has been the sole affected person who has spoken out publicly about gun safety and gun laws.

In reality, Arthur was the only one to call. Since the shooting, he was the sole affected person who had spoken out publicly about gun safety and gun laws. (That is still the case today.) Perhaps, Arthur reasons, it’s because many family members joined a lawsuit related to the shooting and had been advised not to speak out. Or maybe, as Richardson says, it has to do with the fact that they live in Maine. “The gun culture in Maine is so strong that even people who are victims or have lost loved ones to gun violence don’t want to talk about it, because they might offend their neighbor or their friends or their family,” she says. “I’ve lost friends and family over the issue.” Still, when she asked Arthur to speak, he was ready with an answer. “I’ll do it,” he said without hesitation.

A week later, Arthur rose in the morning, put on a navy-blue hoodie with an image of Artie on the back, and set out for Augusta, 40 minutes away. When he arrived in the dull, gray morning light, a long line of people holding anti-gun violence placards snaked outside the State House, waiting to get in.

Taking to the podium, Arthur told the audience packed in rows of chairs that he had spent the past two months educating himself and had realized that loopholes in the state’s gun laws make all of them vulnerable to violence. “This is not about taking guns, okay?” he said. “This is about doing the right thing and finding the right politicians who are willing to do the right thing more than they’re afraid of losing their jobs.” The crowd erupted in cheers and applause. “It’s not a Democratic thing, not a Republican thing; it’s common sense for all of us,” he said, adding that he’d talked to some 75 friends of his who are NRA members and gun owners and was able to find common ground for more sensible laws that balance freedom and safety.

After Arthur spoke, Richardson guided him through the process of engaging with lawmakers and explained that he could leave notes requesting meetings with senators, representatives, and even the governor. This was unfamiliar territory for Arthur, who was still learning about political activism and was unsure which lawmakers represented his district. With Richardson’s help, though, he left notes and talked to lawmakers he encountered in the halls. Most were receptive. Some were not. When he spoke to two representatives about background checks, he says, “They looked me right in the eye and told me they couldn’t support it because it was an inconvenience.”

Later that month, Arthur had another chance to discuss gun laws with someone who held a different view. Only this time, it was someone who had become very close to his heart.

Despite having been shot seven times at Schemengees, Justin Karcher still has a passion for collecting guns. / Photo by Tony Luong

After an arduous two-month stay in the ICU and numerous surgeries, Karcher, Artie’s friend and teammate, was discharged from the hospital right before Christmas. He still didn’t have the full range of motion in his right arm, but he was feeling stronger every day. By then, he’d decided to get back to the hobbies he loved—not just pool, but also buying and shooting guns.

One day this past summer, Karcher retrieved a semiautomatic weapon from the large black gun locker in the corner of his bedroom. The firearm was sleek, heavy, and cold to the touch. Strikingly, it was the same model Robert Card had used to fire seven rounds into Karcher’s body and claim the lives of Artie and 17 others. Karcher had bought it barely three weeks after leaving the hospital. “If I could have, I would’ve bought the exact weapon used to shoot me,” he remarked. “I even asked the FBI if I could have that specific gun, but they said no.”

Guns have been a constant in Karcher’s life since childhood, when his grandfather first taught him to hunt. This passion only grew as he matured, eventually leading him to buy and sell firearms. Remarkably, nothing that has happened in his life—not his father being gunned down in a Walmart parking lot nor his own near-fatal shooting—has dampened Karcher’s deep love of guns and his abiding belief that they make people safer. In fact, upon healing from his injuries—a recovery bolstered by more than $43,000 in crowdfunded support—one of Karcher’s first moves was to expand his collection, adding 20 new firearms to his existing arsenal and bringing his total to around 40 weapons.

Some are antique-looking pistols, with swirly engravings on brass plates and white handles, that look like something someone would use in a duel out west two centuries ago. Some are the kinds of semiautomatic rifles that have been used in the deadliest mass shootings in modern history. Karcher says the model of gun used in the Lewiston shooting, which is one of his favorites to shoot, is something of a statement piece, announcing: “It’s not what the gun did. I don’t blame the gun.”

Karcher thinks people need guns to protect themselves from criminals like Card. Even though his multiple guns, locked safely in his truck when he was shot, were of no help to him, he says that armed people were able to prevent death tolls from being higher during other mass shootings. He also says having more regulations and background checks will “not keep guns out of the hands of people who shouldn’t have them and only make it harder for law-abiding citizens to get them.”

Ready to defend his convictions, he descended one late January night to the basement of a private club for a team competition. Arthur was so happy—not just to see Karcher, but to see him coming to play the game he loved. Ever since the shooting, Arthur felt bonded to Karcher. After all, Karcher had witnessed Arthur’s final moments with his son and was by Artie’s side when he drew his last breath.

“Hey, is there any way we can talk before you leave tonight?”

“Sure,” Arthur said.

“I’m afraid you aren’t going to like what I have to say.”

“There’s nothing in the world that you can’t look me in the eye and say. Ever. You can say anything you want. Nothing is off-limits for you.”

As they disassembled their pool cues in the corner after the game, Karcher, his voice still weak from his lung injury, spoke his mind, aware of Arthur’s advocacy as well as his appearances in newspapers and on television. “I want to ask you if you can just tone it down with the gun-control talk,” he said, almost in a whisper.

Arthur asked Karcher if he even knew what he was proposing, explaining that he wanted a registry that ties each gun circulating in the state and the country to its owner. That way, Arthur said, when authorities come to take guns away from a mentally unstable individual, they can make sure to get them all. That way, he said, when someone kills, authorities can trace the gun.

“You’re not wrong,” Karcher responded, later admitting that he was just trying to seek common ground so he could have a chance to voice his own views, too. Arthur, for his part, has nothing against people having guns. “I would love to take my grandkids hunting, but I can’t,” he says of his prohibition from legally possessing firearms due to his criminal conviction. What he does want is for people to be responsible for their guns. And he would not, as Karcher asked, stop talking about that.

In March, Arthur drove to the State House in Augusta to testify in front of the judiciary committee in support of a series of gun safety bills. When it was his turn to address the committee, he introduced himself, saying he’d lost his son in the Lewiston shooting. Then he voiced his support for the pending legislation and urged lawmakers to go even further by passing a semiautomatic rifle ban and a gun registry for private gun sales. “Right now, there’s no way to make people responsible for their weapons,” he said, his piercing blue eyes peering over his glasses. “We have a right to bear arms, but there’s nothing in that Second Amendment that says we shouldn’t be responsible.”

As Arthur finished talking and turned to go back to his seat, a lawmaker suddenly spoke up. “Can you tell us about your son?” he asked. “Can you tell us his name?”

“My son’s name was Arthur Strout,” he said, breaking down. “Today was his anniversary. He was with his wife for 16 years. Had five children…the kids are the hardest part about this.”

The next month, Arthur found himself back in Augusta, delicately navigating his testimony before the very commission he had hoped to join. (He says he never received a response from the governor to his letter.) At times, emotion threatened to overwhelm him—his voice catching, his speech punctuated by heavy sighs, as he grappled with the memory of his son and the void he had left. In other moments, Arthur spoke with unwavering clarity as he emphasized his points, the spine of his hand gently but decisively tapping the table. His message to the commission was clear: While addressing mental health was well and good, it alone was simply not enough to stem the tide of gun violence.

Ultimately, Maine passed sweeping legislation that requires background checks on advertised private gun sales, mandates a 72-hour waiting period for gun purchases, and criminalizes selling guns to people prohibited from owning them. The governor vetoed a bill that would make bump stocks illegal, and a so-called red-flag law, which enables authorities to take guns away from people who are in a mental health crisis, never came to a vote.

Gun safety advocates across the state celebrated, but Arthur thought the legislation fell short. There was still more advocacy work to be done to honor his son. But first, there was something else he needed to do for Artie.

Arthur spoke passionately about gun laws at the Maine State House in early January. / Photo by Joseph Prezio/AFP

In early May, Arthur returned to Logan Airport, this time headed for Las Vegas. The past few months had been a whirlwind of success for Artie’s pool team. With Arthur on the team, they had rallied from fifth place to clinch the top spot in their league’s regular season. Then they came a hair’s breadth away from taking first place in the Maine championship tournament and finished second. Now, more determined than ever, it was time to go to nationals.When Arthur arrived in his hotel room on the 16th floor of the Westgate Resort, he removed his framed picture of Artie from his bag and put it on a table near the TV, right in front of his bed. I made it here for him, Arthur told himself.

That evening, Arthur and his teammates gathered in the convention hall’s event space, where 152 pool tables stood in orderly formation across the carpet, for a much-needed 11th-hour practice. After all, in the morning, the men were set to compete in a 9-ball singles event, which is not a game they usually play in Maine, and the competition tables were a good 2 feet shorter than the ones back home. Karcher was also competing, making the trip just as he’d planned with Artie. He still wasn’t 100 percent healthy, but he was close.

The next morning, Arthur pulled his blue-and-white collared team jersey over his head. It proudly displayed Maine’s iconic pine tree and star on the back, while the sleeve listed the names of the three fallen Maine players: Maxx Hathaway, Joey Walker, and Artie Strout. Arthur picked up his pool case and touched the photo of Artie with his hand before heading downstairs for his first match at 9 a.m.

Locating his table, Arthur took out his cue sticks, assembled them, and slipped a light-blue glove onto his hand. Arthur had never played with a glove, but Artie did. And this was his glove—the one Artie was wearing the night he died.

Arthur’s first match pitted him against an equally ranked player from California. Still, Arthur had decided to approach every opponent as if they were ranked much higher. As he bent over the vibrant-blue felt, his right elbow held high and his eyes fixed along his cue, the world around him faded away. Gone were his emotions, his sorrow, and his thoughts about Artie. In that moment, only Arthur existed—along with the balls on the table and his single-minded goal: to win.

Arthur won the first game, only to watch his opponent beat him in the second. Then he ran the table for the next four games to win the match. Excited, he found his teammates and told them he’d scored a victory. Though his next match was coming up soon, at 10:30 a.m., he had something he needed to do first. He escaped to his hotel room and touched his picture of Artie before going back downstairs to play.

His next opponent, a player from West Virginia, came out of the gate strong and took the first game. Then Arthur smoked him and won the next five. Once again, Arthur rode the elevator up to his room after the win, touched the picture of Artie, and headed back downstairs for his noon match against a top-ranked player from Las Vegas. They traded games back and forth, but in the end, Arthur notched another victory.

As the day wore on, Arthur’s teammates and fellow competitors followed his success, occasionally gathering to observe his matches from afar. Gradually, they began to realize they were witnessing something special.

In the next round, Arthur faced off against a top-ranked player. Arthur quickly took the first three games. Whoever won would move on to the finals. By now, Arthur’s teammates were rallying around him, offering support and encouragement. “Artie is with you,” they said. Arthur’s opponent bounced back to win the next few games, but then Arthur finished him off. He was headed to the finals.

The following morning, Arthur’s remarkable winning streak continued as he faced some of the best players in the country. It wasn’t until he went up against an old friend from Maine—Rob James, one of the state’s top pool players—that Arthur’s streak ended. If he had to be knocked out, though, Arthur was glad that a fellow Mainer was the one to do it. He ended up placing fifth out of 150 players. “I never anticipated him being able to go that deep in a tournament,” says Shane Bouchard, the Maine league owner, who was also competing in Vegas. “I’m not a religious guy. I’m not a spiritual guy. But something was holding his hand for a couple days there.”

After watching Arthur’s remarkable run in Vegas, Karcher tried to convince his friend’s father to keep competing on the team. After all, Karcher says, he still respects Arthur, and having different opinions on guns or politics is no reason not to like someone. “It doesn’t matter,” Karcher says. “It doesn’t change the person he is.” He knows they both want the same thing—for people to be safe from gun violence—they just disagree on how to get there.

For now, at least, Arthur has more pressing matters than pool, particularly figuring out how to speak to schools about gun law reform.

For now, at least, Arthur has more pressing matters than pool, particularly figuring out how to speak to schools about gun law reform. And in three years’ time, once his grandchildren graduate high school, he plans to retire from cooking and dedicate himself full time to fighting for new gun laws. He had come to Vegas to play for Artie, he told his teammates, and now his days of competing were over.After landing back at Logan and making his way north to Maine, Arthur had someone important he wanted to tell about how it went. And so, with his photo of his son sitting in the back seat, he steered his car toward the parking lot of Schemengees.

First published in the print edition of Boston magazine’s October 2024 issue with the headline, “A Father’s Purpose.”