The Betrayal of Sandra Birchmore

When a Stoughton police officer preyed on a teenage trainee, a nightmare began—and a ghastly crime lay hidden for years. Is justice for Sandra Birchmore still possible?

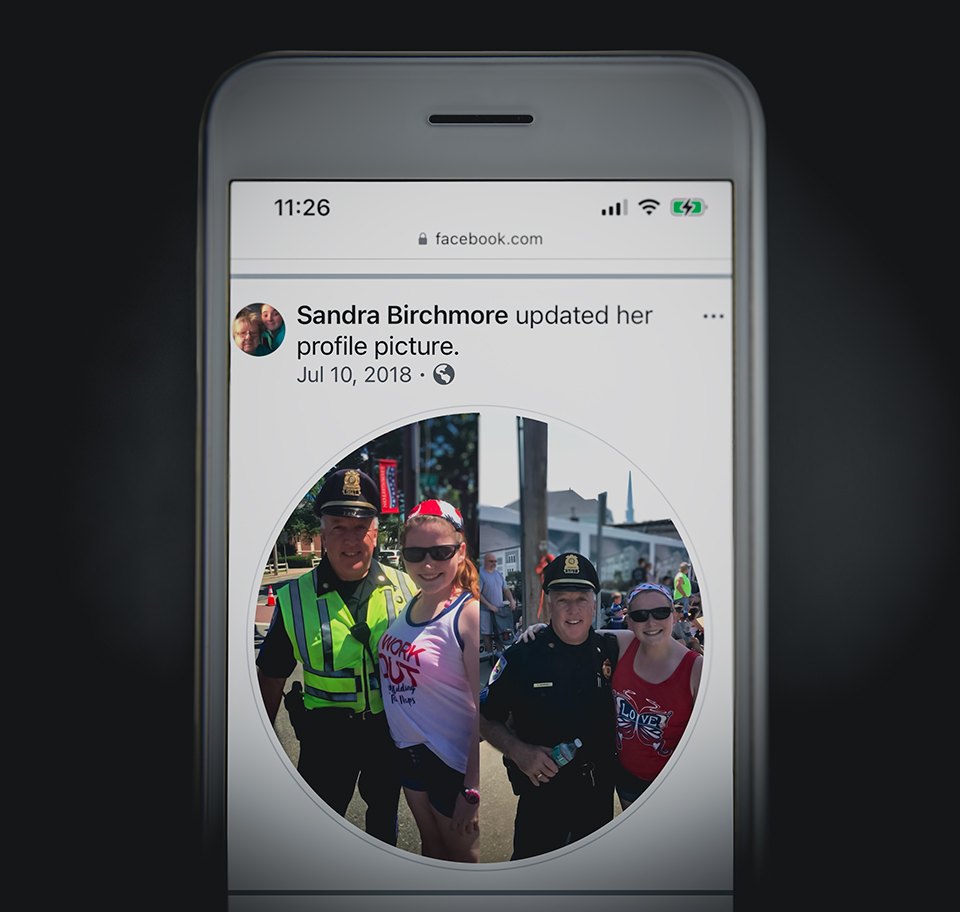

Growing up in Stoughton, Sandra Birchmore idolized police officers. She dreamed of becoming one herself someday and longed to enroll in the town’s Police Explorers program, hoping for mentorship and direction.

Birchmore had long auburn hair, a smattering of freckles running across the bridge of her nose, and a smile that often hid her family difficulties and struggle making friends. At school, she was picked on and bullied, while at home, she and her chronically ill single mom, Denise, often moved around. Sometimes, they lived on their own; other times, they stayed with Denise’s aunt and uncle, Claire and Gerald Gaudet. For much of her life, Birchmore believed they were her maternal grandparents.

On her father’s side, Birchmore had no one. She never even knew her dad. Her mother gave her the last name of her late husband, who’d died years before Birchmore was born. Concerned for her daughter’s future, Denise finally granted Birchmore’s wish in 2010 when Birchmore, only 12, joined the Explorers.

In the program, Birchmore met Matthew Farwell, a policeman who had once been an Explorer, too. Six-foot-four with dark, penetrating eyes, Farwell had dropped out of high school and served in the military before joining the force in Wellesley and then Stoughton. He took Birchmore under his wing, helping her with homework and spending time with her outside the program.

In 2013, their relationship crossed a line, federal prosecutors say, when the 27-year-old cop had sex with Birchmore, just 15, a month before he married his wife. They began a physical relationship that spanned nearly a decade, even as Farwell built a family with his spouse. In late December 2020, Birchmore became pregnant and said Farwell was the father. She was excited about becoming a mother and envisioned one crucial difference between her child’s life and her own: She was determined to put the father’s name on the birth certificate.

Five weeks later, Birchmore was found dead in her apartment. Despite evidence of an intimate relationship and Farwell being the last known contact, local and state police hardly investigated their fellow lawman’s potential involvement. Instead, officials quickly ruled Birchmore’s death a suicide. Case closed. (The following account is based on facts alleged in police, FBI, and court documents; a trove of text messages submitted to the court in an FBI affidavit; and this magazine’s interviews with law enforcement officials.) It would take nearly four years for loved ones, online activists, and ultimately FBI agents to unearth damning evidence that led to Farwell’s arrest on suspicion of killing Birchmore. Farwell, who has pleaded not guilty to a federal charge of killing a victim or witness, has been in custody since August 28. His lawyer, public defender Jane Peachy, did not return requests for comment.

And now, as the state police reel from another embarrassing scandal, one haunting question lingers: Why is justice for Birchmore taking so long?

Birchmore was enrolled in the Stoughton Police Explorers by her mother, who hoped she would find strong role models in the program. / Courtesy of Justice for Sandra Birchmore/Facebook

As a child, Birchmore’s troubled home life was hardly a secret. Beyond the lingering scent of cigarette smoke from a household of smokers, her behavior spoke volumes. “She wasn’t a bad kid,” recalled a former teacher, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Just a child starved for attention, acting out to be noticed. The signs of neglect were unmistakable.”

When Birchmore was nine, she and her mother enrolled in the town’s Strengthening Families Program, a 14-week course aimed at supporting vulnerable families and children. While there are no official records to indicate what prompted them to join, Denise seemed to get something out of the course. “I liked the fact that they showed you what your tools are,” she explained in an interview with the Stoughton Journal after graduating from the program in 2006. “For example, instead of yelling at your child, sit down and talk it out. If you are both angry, instead of trying to work out the situation right then, take a time out and come back and deal with it.”

Despite the course, Birchmore continued to struggle. Andrea Wasoka, Birchmore’s seventh-grade teacher at O’Donnell Middle School, described her as needy and prone to stretching the truth to gain attention. She got along with adults better than her peers, Wasoka said, something that made her “very socially dysfunctional in school.” Kids taunted her relentlessly, and when she sought help from teachers, they bullied her even more.

By the time she was 12, Birchmore was determined to find community outside of the classroom. Though waitlisted for the Stoughton Police Explorers in March 2010, she became a standby member in the program, watching Officer Robert Devine bark orders at teenage cadets. From the outside, then-Chief Paul Shastany recalled, Devine ran the Explorers “like a drill sergeant, like it was Parris Island.”

On the inside, though, Stoughton’s police department was far from shipshape. Federal authorities had set their sights on veteran officer Anthony Bickerton, who was embroiled in an illicit scheme with a criminal informant. His so-called snitch would pilfer high-value items, then Bickerton would help sell them around town. The operation, spanning a decade, ended when Bickerton was convicted in 2010. That same year, the department faced another scandal when Officer Richard Bennett resigned following a foolhardy trip to a Stoughton strip club: While on duty and in uniform, he snapped a picture with an entertainer known as Bridget “the Midget” Powers, billed as “the world’s smallest porn star.”

Blissfully unaware, Birchmore still idealized police officers—a perspective nurtured by Gerald Gaudet, a decorated Army vet who’d stood in as her grandfather and fostered her love for law enforcement. When Gerald died in May 2012, Birchmore felt gutted, her cousin Barbara Wright recalls, describing a young girl suddenly robbed of her North Star who continued to flounder academically and socially in school.

By then, Farwell had secured a job with the Stoughton police, as well as an instructor role with the Explorers program. Starting in 2012, he began to meet Birchmore after school in Stoughton’s 1960s-style, flat-roofed public library, where he helped her study and prepare for tests. Yet homework wasn’t the only thing on his mind. “Did you think I wouldn’t want to fuck you?” Farwell texted Birchmore in June 2019, reminiscing about their time together in the library seven years prior.

Farwell didn’t have to wait very long. The following year, on April 10, 2013, when Birchmore was 15, they had sex for the first time, according to an FBI affidavit. Farwell was particularly proud of taking her virginity even years later, according to his text messages uncovered by the FBI, sending her questions in 2019 and 2020, including, “What was the first day you said omg I want this guy to be my first I want to feel him inside me?” followed by, “I absolutely would have fucked you in…2012”—when Birchmore was just 14. In another text, Birchmore wrote, “I had butterflies so bad the day you took my virginity,” adding that it was the “best day of my life.” Another time, Farwell told Birchmore it was “a big thing to get to be the first.”

As an adult, Birchmore admitted that she started thinking about Farwell sexually when he began flirting with her at the library, but didn’t want to say anything. “Cause of my age,” she’d texted, “I didn’t want you to be like uhhh no wtf.” Another time, Farwell wrote her, “If I pushed I absolutely could have fucked you without condoms from day one,” to which Birchmore answered, “I was kinda scared to say no in the beginning, not knowing how you’d take it.”

Meanwhile, Farwell’s involvement with Birchmore didn’t stop him from pursuing a more traditional—and legal—romantic relationship. On May 11, 2013, he tied the knot with his wife. But his marriage didn’t mark the end of his relationship with a teenage Birchmore: They continued to sleep together throughout her high school years. An FBI affidavit details how Farwell and Birchmore would meet for intimate encounters while Farwell was on duty. The FBI affidavit also shows that Farwell would use “forceful oral, vaginal, and anal sex acts to punish” Birchmore for “getting bad grades, having intercourse with other people, and failing to share her cell phone location.” By 2013, Birchmore’s personal journals described the two incorporating choking into their sexual repertoire.

Nonetheless, Birchmore had made significant academic strides and was on track to graduate on time. In the spring of 2014, her mother penned a letter to Devine. In it, according to Stoughton police internal investigation records, she thanked the Stoughton Police Department—and Devine, in particular—for “running the police Explorers program.”

Robert Devine ran the Stoughton Police Explorers program that Sandra Birchmore joined at age 12. / Courtesy of Justice for Sandra Birchmore/Facebook

On a bright June day in 2015, Birchmore hurried across the Stoughton High football field to collect her diploma. The wind tousled an American flag in the background as she walked across the stage in a cap, gown, and flip-flops, her auburn hair neatly bundled at the nape of her neck.

That summer marked the beginning of a downward spiral for Birchmore. With high school and the Explorers program behind her, she found herself again at loose ends, living at home without much direction. Meanwhile, Farwell’s life seemed to be flourishing. By May 2016, Farwell and his wife had settled into a spacious four-bedroom house in North Easton, purchased for more than half a million dollars, and built their family with two children.

Yet as Farwell’s family life blossomed, Birchmore’s world continued to crumble. In May, her mother died suddenly of a massive stroke at just 52. “It was horrible,” Wright recalled. “Sandra was shattered.” The pain only deepened a month later when Claire Gaudet, the woman Birchmore had always known as her maternal grandmother, passed away at 89.

Though her aunts, Darlene Smith and Alice McKain, moved into Birchmore’s childhood home to help, their relationship often proved tense. In May 2020, conflict erupted over the sale of the house—Birchmore’s only true home. During an argument with Smith, Wright says, the situation escalated, and Smith called the police, claiming Birchmore might harm herself. Responding officers brought Birchmore to the hospital, and after a brief assessment, medical staff determined she posed no risk to herself and discharged her within hours. Soon after, according to the FBI affidavit, Farwell began sexting Birchmore, who later apologized for worrying him. “I wasn’t worried,” he replied. “I know you are fine.”

Birchmore still dreamed of a career in law enforcement and had enrolled in Massasoit Community College’s criminal justice program. At the same time, her relationship with Farwell took on increasingly violent undertones thanks to his appetite for sexual-fantasy role-play. “Maybe I’ll hold you down by your throat while I pound you,” he texted her in 2020, adding that he wanted her to “feel like omg this is really happening and I can’t stop it.” He also shared rape fantasies with Birchmore and instructed her to role-play sex involving pedophilia and non-consensual incest, including pretending that he was her brother coming into her room at night.

During this period, Birchmore also had sex with other men, including Farwell’s twin brother, William “Billy” Farwell, a fellow Stoughton police officer. Hailee Sousa, a close friend of Birchmore’s and a student at Massasoit Community College, told Boston that Matthew Farwell exerted control over Birchmore through dominance and authority, while William Farwell presented himself as “the sweet one, the best friend with benefits. It was a very sick good cop, bad cop relationship she had with them,” rife with elements of BDSM and psychological manipulation.

In their discussions, Sousa remembered Birchmore mentioning an event that took place two years after William Farwell began his career with the Stoughton police in March 2017 while a member of the National Guard. Birchmore was having sex with one brother in her car when the other brother unexpectedly arrived and became upset. Sousa also mentioned becoming aware of another figure in Birchmore’s life emerging around this time. This turned out to be Robert Devine, the man Birchmore first met when she joined the Explorers program. Internal investigation reports later showed that Devine used the moniker “Marty Riggs,” apparently inspired by Mel Gibson’s character in the movie Lethal Weapon, to communicate with Birchmore over Facebook Messenger, discussing sex acts and planning to meet with her while Devine was on duty. “Sandra is a sex trafficking victim,” Sousa says. “They told her to do things and send pictures, videos of it. Matt knew she would be obedient to him. That was the dynamic. They mentally manipulated that girl until she had no voice.”

The content of their texts and the nature of the videos she was asked to share were so alarming that one investigator privy to them says he “wanted to wash his eyes out with holy water” after seeing them.

One of the many pornographic videos now in federal custody, according to several knowledgeable law enforcement sources, features Birchmore with a U.S. Army Reserve recruiter stationed in Quincy. Birchmore, hoping to become a police officer, had sought military service to bolster her credentials and asked William Farwell to connect her with someone who could help. According to an internal investigation report from the Stoughton Police Department after Birchmore’s death, William Farwell introduced her to an Army buddy. Soon, according to a review of Birchmore’s Facebook activity, she and the recruiter became Facebook friends, which violated military fraternization rules related to prospective recruits, and eventually, they had sex, a video of which was shared with William Farwell. Investigators have passed the video along to Army officials. Once a visible public face for Army recruitment at community events, the recruiter did not respond to requests for comment and is no longer stationed at the Quincy recruiting office.

As time passed, Birchmore began to yearn for something she could call her own—a baby. She talked about becoming a mother constantly, Sousa recalls: “She had a plan. No matter what, she was going to have a baby.” This fixation led Birchmore to spend excessively on pregnancy tests, frequently borrowing money from Sousa to fund her compulsion. The financial strain and concerns for Birchmore’s safety began to erode their friendship. Sousa told her that “trying so hard to get pregnant, she was going to get herself killed.”

Matthew Farwell, bottom left, and his twin brother, William, bottom right, were Explorers themselves and went on to work with the program. / Courtesy Stoughton Police Department

In late December 2020, Birchmore sat down in front of a rainbow pack of magic markers and a sheet of posterboard. In girly, decorative script, she wrote, “Congrats we are goin [sic] to be parents!” She placed stickers of baby animals—a smiling monkey, a zebra, a frog, and a giraffe—all along the poster’s borders. Then she snapped a picture of it and sent it to Matthew Farwell.

Birchmore was three weeks pregnant and over the moon at the prospect of being a mother. Farwell, however, didn’t take the news so well. “I have literally nothing to say right now,” Farwell texted. “How far are you?”

“Regardless of how far,” she responded over text, “we’re keeping it.”

“Okay well we need to talk then,” he replied.

Birchmore answered with uncharacteristic snark. “No shit. That’s obvious.” Then she added a crucial imperative: “And the birth certificate is being signed.”

Birchmore’s life had recently taken a positive turn. In October, she’d landed a new job as a teacher’s assistant at East Elementary School in Sharon, along with a cozy one-bedroom apartment in Canton. With her cousin Wright’s support as a cosigner, she also secured a loan for a 2018 Chevy Cruz. Though Birchmore had continued to pursue her dream of becoming a police officer by taking the civil service test, Wright says, she also began following a new career path by enrolling in nursing classes. Most significantly, though, for the first time since she was 15, she realized she held sway in her relationship with Farwell.

The catalyst for Birchmore’s decision to leverage this newfound power came from an unexpected source. Stoughton Animal Control Officer Joshua Heal—who admitted in his response to a civil lawsuit filed by Smith, Birchmore’s aunt, that he received oral sex from Birchmore on a couch inside the town animal shelter—informed her that Farwell was expecting a third child with his wife. This news came as a blow to Birchmore. According to the FBI affidavit and sources close to the case, she confided in Heal, revealing everything Farwell had sworn her to secrecy about: her unconventional relationships with the Farwells and Devine, and the explicit, often violent messages Farwell had sent her. (In civil lawsuit court documents, Heal says his sex with Birchmore was consensual, and a judge dismissed a battery of civil claims that Birchmore’s aunt had sought to bring against him.)

Birchmore’s next move? She drafted a message to Farwell’s wife, poised to disclose Farwell’s decade-long affair. However, instead of sending it, she saw an opportunity and presented Farwell with an ultimatum: In exchange for her silence, he would have to agree to unprotected sex for the purpose of conceiving a child.

Farwell said yes but had specific plans for how the sex would play out. “You say no and make me take it. Full r word,” he texted her. Another time, before meeting up, she asked before he arrived, “Do you want me to just take what you do or try and say no? I know being told no is your favorite.” He responded, “say no.”

Messages between Birchmore and Farwell, according to the FBI affidavit, show she was determined to conceive. And in the process, she assured Farwell that she wouldn’t “talk shit about [your wife] or your kids. That way we both get what we want.”

Birchmore’s persistence paid off. After a series of negative pregnancy tests, she found herself face-to-face with a long-awaited positive result. But her fragile arrangement with Farwell began to fall apart when a colleague of Farwell’s informed him that one of Birchmore’s friends had contacted the station, exposing what the friend called their “illicit sexual relationship.” Farwell, panicked, urged his coworker to keep quiet about the call and immediately reached out to Birchmore. “I literally can’t believe this is even real life like what else do I have to worry about now?” he wrote her. “Which other friend will do something tomorrow?”

In January, Birchmore confided to her baby’s godmother-to-be via text that Farwell had snapped when Birchmore showed him a sonogram image, saying, “That’s not my child!” and pushing her to the ground. That same month, Farwell asked for a key to her apartment, which she made for him at a nearby Walmart. When he showed up to retrieve it, his behavior raised her suspicions as he inspected her bathroom and closet. “It was just really odd he started looking around I don’t know,” Birchmore texted a friend.

“That’s weird,” her friend responded.

“Yeah it was really weird,” Birchmore texted back.

Despite these red flags, Farwell seemed to allay Birchmore’s concerns. She told her friend, “Maybe he’s coming around.”

Courtesy of Justice for Sandra Birchmore/Facebook

On February 1, 2021, as a nor’easter barreled toward Massachusetts, meteorologists predicted heavy snowfall across the region. When Sharon Public Schools, where Birchmore worked, announced an early closure, she immediately texted Farwell, apparently hoping to spend the cozy snow day together. He tersely replied that he wouldn’t be in the area.

Unbeknownst to Birchmore, Farwell had more immediate demands: His pregnant wife was about to give birth. Birchmore, though, was preoccupied with her own pregnancy. In the days before her death, she’d planned her pregnancy announcement for Valentine’s Day, as well as the gender reveal, and made an OB-GYN appointment for a few weeks out. With no detail too far off in the future, she even arranged for someone to watch her two cats around her due date.

That afternoon, Birchmore texted Farwell about a baby gift that had been delivered to her Canton apartment and then shared her excitement for a March baby shower. She ordered DoorDash delivery, picked it up in the lobby at 5:01 p.m., according to security surveillance, and briefly went outside to scrape snow off her car, returning at 5:33 p.m.

Throughout the evening, Birchmore casually moved from one activity to the next: She texted friends and shopped online for baby furniture. She chatted with Wright, who was in Seattle, over Facebook and threw a load of laundry into the dryer and another in the washing machine. Then Farwell texted her at 9:08 p.m., wanting to know if he could “come by for a second,” the FBI affidavit reveals. Two minutes later, she texted him back that the door would be open. Four minutes after that, security footage captured Farwell, wearing a hoodie and a face mask, entering Birchmore’s building. Her cell phone cataloged her final steps at 9:40 p.m. Three minutes later, at 9:43 p.m., cameras recorded Farwell’s speedy exit.

Security footage from Birchmore’s apartment foyer on the day she died.

The next morning, a new life entered the world: Farwell’s wife gave birth to the couple’s third child, a boy. Later, thanks to the investigative efforts of podcaster Kirk Minihane, the first journalist to raise questions about Birchmore’s case, a startling photo emerged: Farwell, cradling his newborn son, still wearing the very outfit he’d worn hours earlier at Birchmore’s apartment under the watchful eye of a security camera.

By the frigid morning of February 4, 2021, Birchmore hadn’t been seen in days. Concerned, staff at her school requested a wellness check. As snowflakes swirled in the biting wind, Canton police arrived at Birchmore’s apartment complex. They banged on her locked door—the same one she’d left open for Farwell. No answer. After circling the parking lot, police reports show, they found her car buried under snow. With a key from the property manager, they carefully entered Birchmore’s home.

Officers moved cautiously through the cluttered kitchenette and living room and past a tidy bathroom. When they entered Birchmore’s bedroom, according to police reports, a desk lamp illuminated an unmade bed, Christmas lights blinked around a window, and eyeglasses lay discarded on the mattress. On the floor, Birchmore’s body sat upright, a black strap around her neck tied to the closet doorknob. Her cell phone lay roughly a foot away, just beyond her grasp.

The official response was swift but mechanical. Officers at the scene called their supervisor, who contacted state troopers. Though Birchmore was beyond saving, emergency medical responders were still called to the scene, with a Canton firefighter putting on Tyvek booties and confirming her death at 11:46 a.m., according to police reports. In his report, the state trooper overseeing the case noted that there were no signs of anything suspicious. It appeared to be a tragic case of suicide.

After Birchmore’s death, women have primarily driven the push for justice, mobilizing people online and in protests. / Courtesy of Justice for Sandra Birchmore/Facebook

The phone call that ripped Darlene Smith’s world apart came from an unexpected source: Canton police. They had found Birchmore’s body, and Smith was listed on Birchmore’s lease as the emergency contact. Smith’s lawyer says that the person on the other end of the line claimed Birchmore had taken her own life. Instantly, Smith knew with bone-deep certainty that this wasn’t true. When she spoke with Wright, Birchmore’s cousin, on the phone, both women shared the same misgiving. “We agreed something just wasn’t right,” Wright recalls. “We didn’t believe it was a suicide.”

Indeed, a read of state police reports from the scene that day does, in hindsight, suggest some potential oversights. The same trooper who’d initially noted “nothing suspicious” at Birchmore’s apartment reported examining Birchmore’s body for signs of physical abuse—including grab marks, scratches, strikes, or defense wounds—but found none. He also noted “no markings on the neck to indicate an attempt or struggle to loosen or remove the ligature.” Notably, investigators quickly determined Birchmore’s death was a suicide (later confirmed by the state’s medical examiner). However, says Joe MacDonald, a retired veteran homicide investigator for the Boston Police Department who now runs MacDonald Investigations in Pembroke, “Just because it looks like a suicide doesn’t mean that it is. No law enforcement officer can make that determination.”

Despite their investigation, state troopers also overlooked at least one crucial piece of evidence: Birchmore’s cherished necklace—a delicate gold chain adorned with a pink flamingo charm—discovered by her family, according to the FBI affidavit. The necklace lay broken on the floor, entangled with a clump of hair. The origin of the hair remains a mystery, as it was never mentioned in any initial police report. Oddly, while this potential clue went unnoticed, the state police report did include a comment on Birchmore’s housekeeping, noting “trash and clumps of cat fur on the carpet indicating that it had not been cleaned or vacuumed in some time.”

Later, an FBI agent’s review of the state police crime-scene photos revealed the startling oversight. In her affidavit, she noted the necklace was clearly visible in images taken before Birchmore’s body was moved to the morgue and cremated, the broken chain hanging from the left side of Birchmore’s neck while the pink flamingo charm rested on her abdomen.

Additionally, Birchmore’s behavior on the day of her alleged suicide was hardly that of someone planning to end her life. After all, she’d made appointments and performed routine tasks like clearing snow off her car. Her therapist, who had seen her just the day before, told the FBI that Birchmore had expressed no suicidal thoughts or ideations leading up to her death. Despite numerous calls to local and state police from Birchmore’s friends and family pointing to Farwell as a suspect with the means, the motive, and the opportunity to kill Birchmore, investigators seemed to dismiss him as a suspect. “I told them Matt Farwell killed her,” Wright said. “No one listened to me.”

Meanwhile, state police pursued leads at Birchmore’s workplace, though interviews with her coworkers, who had only known her since October—roughly four months—yielded very little. They described Birchmore as “seeming off” but never mentioning abuse or fear related to her “boyfriend,” identified only as a Stoughton police officer. One teacher labeled Birchmore “an oversharer,” a trooper noted, but had “never mentioned anything about the boyfriend being mean to her.” Another coworker affirmed Birchmore never “expressed any concerns for her safety.”

Smith, Birchmore’s aunt, was one of the first people to bring Farwell’s name to investigators, according to state police reports, but it wasn’t until two days after Birchmore’s body had been discovered that Farwell’s involvement as the last person to likely see Birchmore alive became official: Surveillance footage from Birchmore’s lobby captured his imposing figure, which state troopers cautiously described as “a male believed to be Matthew Farwell.” Even then, the report concluded that the security tape provided no further information as to what happened.

Above: Security footage captures Farwell, wearing a hoodie and a face mask, entering Birchmore’s building.

Below: Security footage showing Farwell’s exit. (Note: The video timestamps are inaccurate by 13 minutes.)

Still, the video was enough evidence to at least warrant an interview with Farwell. A state police sergeant, also a Stoughton native and former Stoughton police officer who still occasionally played for the department’s hockey team, took it on despite an arguable conflict of interest. The extent of the sergeant and Farwell’s prior relationship is unclear, but the language the sergeant used in his reports is decidedly chummy. After meeting Farwell in a school parking lot, the sergeant consistently referred to him as “Matt” throughout his reports rather than using more formal titles such as “Mr.” or “Detective Farwell.”

In his report, the sergeant detailed Farwell’s account of his relationship with Birchmore, painting a chaotic picture. Farwell spoke of learning about Birchmore’s death and feeling sympathy for what he called her “troubled life.” He described a drunken sexual encounter in 2020 and claimed their last intimate contact was in October of that same year. Farwell denied paternity of Birchmore’s baby and recounted a visit to her apartment on February 1, during which the two argued—he called her “crazy,” and she called him “a dick.” Still, Farwell maintained that Birchmore showed no signs of being suicidal when he left her apartment. He also told state police that Birchmore had other sexual partners during their time together.

On February 9, 2021, Farwell surrendered his personal phone to state police. Months later, Farwell’s work phone from the Stoughton police was also logged into evidence. State troopers performed a data extraction on both devices, yet curiously, found nothing of interest. Farwell’s phones, the state police duly reported, surprisingly held very few clues.

After Birchmore’s death, women have primarily driven the push for justice, including Stoughton Police Chief Donna McNamara. / Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The day after Birchmore’s body was found, Stoughton’s first female police chief, Donna McNamara, was growing increasingly concerned about the numerous statements the department had received regarding Birchmore’s involvement with the Farwells and Devine. She initiated an internal affairs investigation led by Deputy Chief Brian Holmes, who recruited retired State Police Captain Paul L’Italien and forensics expert Michael Bates, lauded for his work that led to charges against Michelle Carter, a Massachusetts woman who had been convicted of involuntary manslaughter for urging her boyfriend over texts to kill himself.

Within weeks, the private and internal investigators uncovered thousands of text messages between Farwell and Birchmore, contradicting the state police sergeant’s official report, which claimed to find no communication between Birchmore and Farwell on either phone—stating Farwell “had deleted all communications with Birchmore.” The sergeant’s separate report concerning Birchmore’s laptop data mentioned “approximately 12 months of iMessages, social media content, and other documents/databases” and alluded to “sexual relationships with other men” but found no threats of harm from anyone, including Farwell. However, the internal affairs report found much more relevant information in the text messages, which showed there was, in fact, evidence of statutory rape. As a result, the Stoughton Police Department placed Farwell on paid leave in February 2021, though officials did not press felony charges. And for years, the case languished in limbo.

The tide began to turn in 2023, when Minihane released his podcast about Birchmore’s case. Among his listeners was Melissa “Mizzy” Berry, a content creator who specializes in advocating for families of homicide victims. The podcast inspired her and a friend to take a deeper interest in Birchmore’s case. “Nobody was talking about Sandra, so I started the Justice for Sandra Birchmore Facebook page in February 2023,” she explains. “I messaged every person affiliated with Sandra, and Barbara got back to me.” Wright, Birchmore’s cousin and cosigner on her car loan, was among the last people to communicate with Birchmore on the night of her death. “Sandra called her all the time,” Berry says. “Nobody thought she committed suicide. Nobody.”

In August 2023, members of the Facebook group gathered outside Norfolk District Attorney Michael Morrissey’s office seeking answers. “We wrote letters and had flyers and marched to his office,” Berry says. “He was supposedly on vacation.” Undeterred, the group’s social media efforts snowballed, keeping Birchmore’s death in the public eye. It helped that the case also shared similarities with the Karen Read investigation—both were handled by the Norfolk DA’s office. As a result, Justice for Sandra Birchmore drew supporters from the Free Karen Read movement, growing Berry’s Facebook page to more than 14,000 members.

Unbeknownst to Birchmore’s supporters, FBI agents had been conducting their own investigation—and their findings painted a starkly different picture from the state police’s official narrative, unearthing thousands of text messages dating back to 2019. The feds also brought in Bill Smock, an asphyxiation and strangulation case expert who had testified at the Derek Chauvin trial in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Smock’s analysis challenged the state police account, noting that the fracture in Birchmore’s hyoid bone was inconsistent with the seated position in which she was found, according to the FBI affidavit. As Smock explained to the FBI, seated hangings, classified as “incomplete hangings,” apply only partial body weight to the neck. During his extensive review of forensic literature, Smock also found no reported cases of hyoid bone fractures in seated women. Rather, he told the FBI, such fractures typically occur in strangulation assaults or full-body weight hangings, not seated ones.

On August 27, 2024, the FBI’s compelling evidence against Farwell convinced a federal judge to issue an arrest warrant. The following morning, unaware of his impending fate, Farwell—now a truck company owner rather than a police officer—set out for Revere in a gravel truck. As he pulled into a strip-mall parking lot outside Sally Beauty Supply, a team of heavily armed FBI SWAT agents swarmed his vehicle. With weapons drawn, they ordered Farwell, clad in jeans and a T-shirt, to step outside with his hands up. He offered no resistance as officers arrested him on charges of killing a witness or victim and recited his Miranda rights.

Courtesy of Justice for Sandra Birchmore/Facebook

That afternoon, Farwell appeared in a South Boston federal courtroom for the first time. Prosecutors argued vehemently against bail, according to court filings, saying that the veteran officer had “killed Birchmore, a young pregnant woman, whom he had spent years sexually exploiting.” They claimed his actions were “designed to conceal forever the truth about his years of criminal conduct targeting Birchmore,” that his “conduct reveals such an indifference to human life” that he is a danger to both children and the community. Acting U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Joshua Levy later weighed in during a press conference: “Mr. Farwell went over to her apartment that evening and he strangled Sandra Birchmore to death. And he used his knowledge and experience as a law enforcement officer to stage her death to make it look like a suicide,” he said. He covered his “tracks” in an attempt “to get away with murder. And he almost did.” Levy noted he is sharing the FBI’s “dogged investigation” with the Norfolk County DA and the state police so they can assess whether “state charges” are warranted.

Later, in September, Farwell waived his detention-release hearing, opting to stay in federal custody. It’s uncertain whether he had anywhere else to go: His wife has remained silent about the case and has scrubbed all online traces of Farwell with herself and their three children.

In the wake of Farwell’s arrest, the ripples of the disturbing case continue to spread. His twin, William Farwell, was placed on leave in 2022 and has since lost his law enforcement certification after it was revealed that he executed unauthorized searches of the law enforcement database on himself and Birchmore, as well as lied to authorities about his relationship with her. Internal investigation records also show that he knew Birchmore was pregnant with his brother’s baby and repeatedly had sex with her, including 22 days before she died. He’s since left Massachusetts and now serves in the Arizona National Guard. Stoughton police placed Devine on leave in April 2022, and he later resigned in August 2022 following internal affairs findings about his relationship with Birchmore. Joshua Heal, the former Stoughton animal control officer, recently resigned from the Abington police force—where he was an officer from 2019 to 2022—and is cooperating with the ongoing federal investigation.

Meanwhile, as Farwell awaits trial, the Justice for Sandra Birchmore movement continues to grow. What began as a small group of concerned citizens has evolved into a formidable force, advocating for accountability and scrutinizing both the alleged abusers and the law enforcement officials they believe failed to thoroughly investigate Birchmore’s death. “It’s growing every day,” says Berry, “and we’ll be out there until they’re held accountable.” No matter how long it takes.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, call or text 988 or go to 988lifeline.org. For confidential support and resources related to sexual assault, call 800-656-HOPE or go to rainn.org.

First published in the November 2024 print issue.

Michele McPhee can be reached at michele@michelemcphee.com.