Confessions of an Accidental Stay-at-Home Dad

Diapers, tantrums, and career curveballs. Parenting wasn't the full-time job I expected.

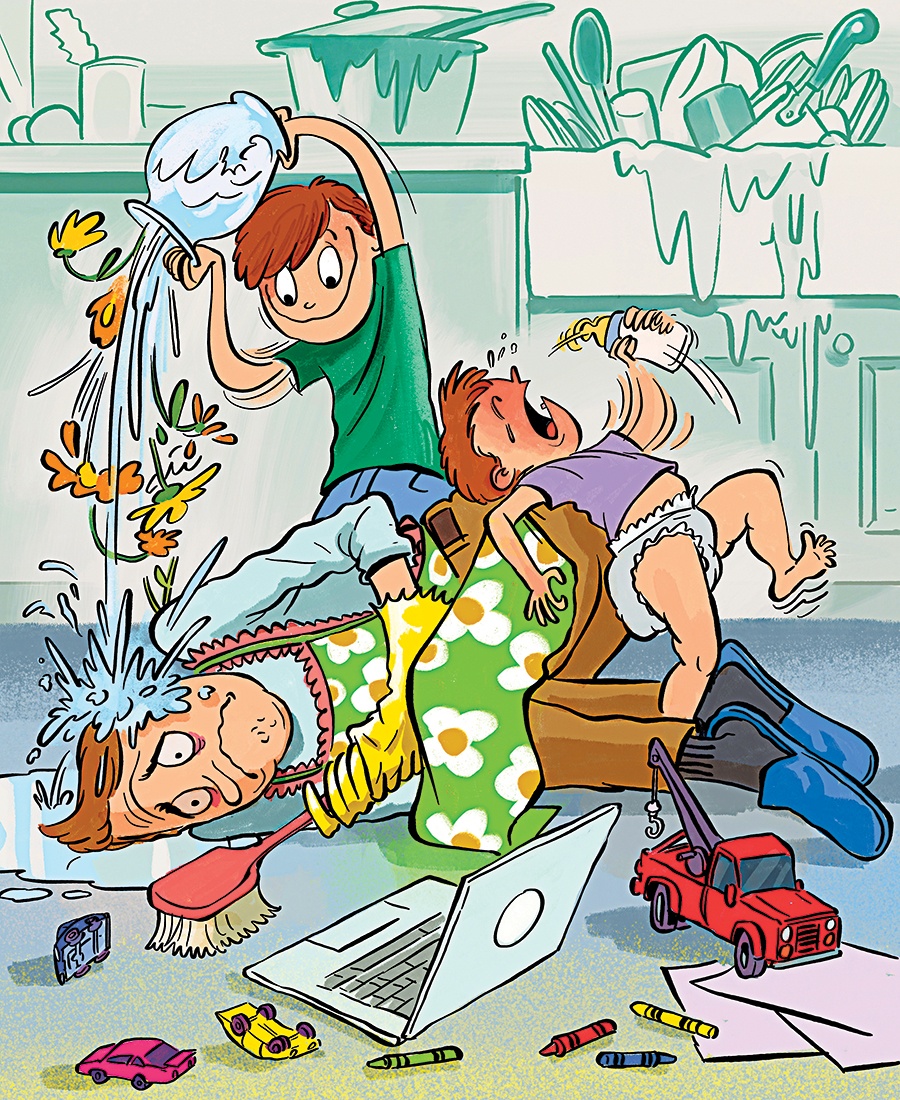

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

“What happened?” The front-desk attendant at urgent care was curious.

“I cut it by accident,” I said, holding up my pinky, wrapped in a bloody paper towel.

“Avocado?”

It was not an avocado. It was too elaborate and shameful to admit in the lobby. Behind closed doors a little later, a PA also asked if it was an avocado. She poured pink liquid on my wound, and I told her the truth. “It was a butter knife into a cutting board in the kitchen, Colonel Mustard, and so on.” As she stitched, I told her how I was making dinner for my two sons, both under the age of three, when I lost it.

It was nearly 5 p.m., so close to the finish line. Reinforcements would arrive in the next hour in the form of my wife, but for now, the battle was mine. I was cooking mac ’n’ cheese with a phone in one hand and a metal spoon in the other, and I dropped the spoon into the boiling water. The kids were screaming and throwing something fragile and touching something sharp, and I fished out the metal spoon with another utensil and picked it up with my bare hand, which hurt, a lot. And I yelled, “WILL! YOU! JUST!”

Rather than finish my sentence, I grabbed a butter knife, lifted it high above my head like Jafar wielding his dagger in Aladdin, and sunk the thing into a cutting board. As the cutting board stopped the knife, my hand slid down the dull blade. What am I looking at here? Bone? Finger fat?

“Daddy hurt,” said my two-year-old when he saw the blood.

This PA understood me because she also had two kids under three, and when I told her I was a reluctant stay-at-home dad, she said, “I couldn’t do that.”

“I’m not sure I can, either,” I admitted.

I always wanted to be a dad…but a stay-at-home dad? A SAHD? I’ve never liked the sound of that. It felt like giving up, like putting down my hunting spear and picking up basket weaving and filling that basket with laundry and also babies. Wasn’t I a hunter? Didn’t I have hair on my chest? Couldn’t I open jars with tight lids? It turned out that while I was searching for success as a writer, walking around with a tiny spear-shaped pen, my wife had found success as an architect. So for the past two years, I’ve been doing what many women have done—and made look easy—since the dawn of time and marriage: supporting my family by taking care of our kids.

My wife writes me notes on my birthday, on Father’s Day, and sometimes for no occasion at all, telling me how much she appreciates me staying with the boys. Not an emotional person, her eyes fill when she talks about how she knows this isn’t how I imagined the first few years of fatherhood, but she’s grateful. What I wonder is, can I learn to be grateful, too?

On my second date with my now-wife, I asked her if she wanted kids. People will tell you this is not a good dating strategy, and they are correct. She said something like “Maybe,” and I decided that sounded a lot like “Absolutely.” We could figure out the details later.

My wife is from Kansas City. It’s cooler than you’d think and mostly as traditional as you’d expect. Most of the women she grew up with had babies, stayed home to care for them, and, as far as she knew, had, or pretended to have, happy hearts about the whole thing. My wife did not want to be a stay-at-home mom; she wanted to be an architect.

Outstanding, I thought before we were married. I could already tell that having this woman stay at home with toddlers full time would be like having a cheetah wear a parachute; it would be weird. And we’d all be thinking, how did this cheetah get a parachute?

Plus, I actually thought I’d be good at staying home with kids. When I was eight, my mom told me I was a natural with children, which struck me as funny: It was like telling a turtle he’s a natural with other turtles. But somehow, it became part of my identity.

So I made the decision, almost two years ago, to stay at home with my kids for one month. I even told God, “Only one month, okay?” I was job hunting and writing, and I would cherish the time with my boys. We could go to the beach on a warm Monday, check out the MFA on a rainy Tuesday, and hit up a brewery Wednesday to Saturday. It would be amazing. Anyone can do a job for only one month. Besides, these are my own kids we’re talking about! This time was a gift.

It was not, in fact, only a month. One very hot day this past July, as I screamed my lungs out into my toddler’s pillow, I wondered how much longer I could keep this up. My youngest child, Kenneth, was 16 months old, the same age as my job search. No matter how I packed the weeks with networking, LinkedIn connections, and clever introduction emails, I remained jobless.

My tiny kids must have sensed I was vulnerable that afternoon, because they attacked! And they were persistent and creative, mixing physical pain with psychological warfare. Look, they’re snotting on my freshly laundered shirt, now they’re jumping into a pile of neatly folded clothes, now they’re smacking my nose with a mini hockey stick, and now they’re swinging that medieval mace-like toy around in circles in the living room even though I told them about the French doors and they break one of the window panes on the French door and there’s glass everywhere and I’m doing breathing exercises while looking up “how to fix a window pane on a French door.”

My wife was due home from work in 211 minutes. Could I last that long? Survive till she arrived, pass the torch, pour myself a stiff drink, and do the same thing tomorrow and the day after that? This was no way to live.

At some point, I realized my kids do not care about my life. The faster you learn this, the more you understand them. They don’t care about the things I used to do, the parties I used to attend, and the friends I could see without first accepting a calendar invite. Hopes for career success are not top of mind for children, and they care little about my dreams of someday not having to fly Spirit Airlines. Above all, they certainly don’t care how important their nap schedule is to our collective future.

“Don’t you get it?!” I want to scream, and sometimes do. “I’m supposed to get everything done NOW! I’m supposed to write, clean, start dinner, exercise, find a job with a salary and benefits, and more, probably!”

My kids smile back, thankfully unaware of how fragile life feels these days. Our bank account was laughing at me, too: “This is unsustainable!” it said in Pee-wee Herman’s voice. “You think you can live on a single income in this economy? In this city?”

The time with my kids was not a gift; it was a cartoon box disguised as a gift, and when I lifted the lid, I saw two cartoon bombs with lit fuses. Now, I love these cartoon bombs very much, and I can almost hear people who have made the decision not to have cartoon bombs yelling, “This idiot shouldn’t have procreated!” Meanwhile, if I talk to anyone with cartoon bombs who isn’t with them full time, I get a special blessing from them, like they are clergy and I’m a missionary reporting back from Neverland or Narnia. I mean, the reverence.

My mom was with us full time: four kids under six, bless her. She didn’t complain, but she did bottle it up like a good New Englander. My mom is a hard-working Yankee who relaxes by landscaping; to complain is not in her, but sometimes that bottle overflowed out of her.

“Yellow light, guys,” one of us would whisper to our siblings when my mom was clearly on edge after we spent the entire day pushing her there. When something would suddenly fly through the air, one of us would say, “Red light.” And we’d retreat to our rooms, close the doors, and wait for the storm to pass. As a kid, I wondered about all of this commotion. Sure, we were a little unruly, but this seemed like a lot.

Now, I have plenty of sympathy. Anyone who says staying home is easy is just flat-out wrong. Having worked in a variety of industries, including journalism, construction, and higher education, I can say this is the toughest job I’ve had. And it’s probably tougher for men than women because—let’s face it—men are generally less tolerant of mental pain and stress. This job isn’t like competing on American Ninja Warrior; it’s akin to captivity survival training. And there are no prizes for winning or certificates for completion.

One time during our high school years, my older brother—and probably me, too—provoked our mom until she snapped and said, “What do you think my reward is as a mother?” My brother replied, “I don’t think there is one, Mom. It’s a thankless job.”

A few weeks ago, I was sitting at a bar in Charlestown for my friend’s birthday when one of the women at our table asked me the question: “What do you do?”

I used to like this question because before I had kids, I got to say, “I’m a producer,” or “I do business development,” and those things sound impressive to me. I produce. I develop. I see progress and results right there in front of me, every day.

These days, I often say, “I’m unemployed,” because I don’t have an employer contributing to my 401(k), but that night I said I was a stay-at-home dad. She lit up. “My dad stayed home with us! We really loved it.” I wanted to ask her so many questions. Did he like it? Did he have hopes and dreams? Did he ever get really mad? Were you well-behaved kids, and that is why everything worked out so well? Do you think I’m having a hard time because my kids are tiny domestic terrorists?

All I could manage to utter, though, was, “Really.”

Afterward, I realized that her comment made me feel as though I’d been lifted off the ground in a hot-air balloon and presented with a bird’s-eye view. I saw my kids as twenty- or thirtysomethings, talking about their dad staying home with them. What would they say about me? “We loved having him at home. What a special time. Going to the zoo, doing work in the backyard, cooking…. When he wasn’t murdering cutting boards, he was wonderful.”

Still, I can’t help feeling the pull that, for the past thousand years or possibly forever, many men have felt—the one that tells me to align my identity with my career. Remember when we were so intertwined with our work that we were named after our…jobs? Baker of bread; Miller of wheat; Smith of iron; Fletcher, maker of arrows; Archer, shooter of those arrows; Sexton, actually not a gigolo.

My father is the CEO of a company, his father was the CEO of a company, and his father before him sailed to the United States from Italy, along with his wife and 13 kids, and then started a company. Sometimes, I imagine telling that guy who landed here in black and white, the guy who called my grandfather “soft” when he helped my grandmother with the dishes: “Papa Giovanni, I’m a stay-at-home dad!”

“Mi scusi?”

“Yeah, my job is to take care of the children.”

“Non ci posso credere!”

“Oop, I don’t speak Italian.”

“Mamma mia!”

I think what I am dealing with, at its root, is how I see myself: as a writer at that point in his career before he’s successful, so he has to stay at home with the kids. But I wonder if I could shift my perspective and tell myself: I get to be home with them for a little time in the grand story of our short lives. I get to see their first steps, hear their first words, bandage their first cuts, and watch them become people.

Someone once told me, “No one ever gets to the end and says, ‘I wish I spent less time with my kids.’” I can’t remember who said it, but I know he was older, I know he was right, and I know I needed to hear it.

I hope I haven’t missed the opportunity to be grateful for this time. When I texted my mom to ask her how she feels about having done a “thankless job,” part of what she told me is, “The reward is often unseen and always long term.” In other words, it’s hard. Especially today, where so much of what we want we can have immediately, and with little effort and discomfort.

One of my favorite moments with my kids is picking them up from the YMCA childcare when I go to the gym. I’ve been away from them for about an hour, I’ve had a workout and a shower, and I see them being good little humans for other people. I see them playing nicely, for the most part, and I’m reminded of the job that I’m doing to prepare these kids to be active participants and positive contributors in this world.

It would be pleasant to end this here, where we all feel cozy and I look sane, but being grateful and having patience are two things that require work. After reaching this eureka moment, I would like to tell you that I am a changed man, that my two-year-old didn’t find another mace-like toy and swing that around in the living room after I told him not to. I would like to tell you that there is not a new crack in another windowpane, and I would like to say that I did not take this mace-like toy, break it into five pieces, and throw it in the trash. I’m working on it, okay?

Every job takes work.

Bart Tocci is a writer and stay-at-home dad who lives in Boston.

First published in the print edition of Boston magazine’s November 2024 with the headline, “Daddy’s Home and He’s Losing It.”

Readers’ Favorite Essays

- My Dad’s Last Day in Court

- Why I Left My Dream Job at WBZ

- The Case Against Trying To ‘Have It All’

- Why I Left the Boston Ballet