The Greater Boston Eviction Crisis Will Hurt You, Too

Skyrocketing rents are displacing the people who staff our hospitals, support our universities, and operate our restaurants. What happens to a world-class city when its essential workers can’t afford to stay?

Betty Lewis has lived in Mattapan’s Fairlawn Apartments for 40 years. Like thousands of Bostonians, she is now facing eviction after her landlord raised her rent to an amount she cannot afford. / Photo by Tony Luong

Morning light spilled over Boston as Noreli Vasquez unlocked the black front door of her brick walkup near Maverick Square in East Boston. Tired after another night shift cleaning MIT’s math department building, she dragged herself down the hall to her apartment. And that’s when she saw it: an envelope taped to her front door. The notice inside made her heart stop—she had 15 days to leave for unpaid rent.

Vasquez burst into tears as her mind spiraled: Where will I go? What will become of me? Am I going to wind up sleeping on a park bench?

She had emigrated from Colombia in 2019, landing a night cleaning job at Boston’s Park Plaza hotel shortly after her arrival. There, Vasquez met a kind-hearted cook—precisely the type of person she had prayed for. Within a year they were married, and by 2021 they had moved into a tiny one-bedroom that was scarcely big enough to contain their happiness. He paid the rent, which was then $1,550 a month; she used her salary for bills, food, and to send money home to her mother in South America.

Then, in December 2023, tragedy struck. During a trip to Colombia to visit her family, Vasquez’s husband fell ill and started behaving oddly—the first signs of what would prove to be a devastating stroke. He never returned to their apartment. Today, he lies in a Peabody nursing home, unable to breathe on his own or move anything other than his eyelids.

After the stroke, his family members took over his financial affairs, paying the rent from his pension. So when Vasquez found the envelope taped to her door that morning, she called a relative to ask what was happening. His cruel response left her reeling. She was nothing to her husband, he told her, and he’d stopped paying the rent three months earlier. Vasquez had already covered some of her husband’s bills that month. There was no way she could also manage the rent—which had increased nearly 20 percent to $1,850 in three years—let alone the three months of back rent she now owed.

Experts consider anyone paying more than one-third of their income in rent to be “rent burdened.” Vasquez’s $1,850 rent consumed two-thirds of her monthly $2,800 income—double the threshold. There was no way she could afford it moving forward.

Organizers from City Life/Vida Urbana and community members show up to support tenants facing eviction. / Photo courtesy of City Life/Vida Urbana

Feeling desperate, Vasquez went to a meeting at the nonprofit City Life/Vida Urbana, which connected her with a pro bono attorney. Housing court bought her more time, but she couldn’t bear the thought of the constable showing up to remove her belongings in broad daylight, in full view of her neighbors. “I knew that they would throw me on the street one way or another,” she said. “And I was embarrassed.” So she moved out on her own.

Vasquez’s story—playing out in homes throughout the city, where 65 percent of households are occupied by renters—reflects a mounting civic emergency. Housing lawyers and advocates say evictions have reached crisis levels, causing a wave of displacement that is ruining lives and fraying the social fabric of communities in Boston and beyond.

The culprit is a perfect storm in the real estate market. Greater Boston’s severe housing shortage has pushed the rental vacancy rate down to a mere 2.5 percent over the past few years, according to the Boston Foundation’s latest Housing Report Card—far below the 7.4 percent that housing advocates consider healthy. Among the nation’s 75 largest metropolitan areas, only two have lower vacancy rates.

This scarcity has helped make Boston among the most expensive rental markets in America for two-bedroom apartments. Even including more-affordable southern New Hampshire communities, the Greater Boston area’s median two-bedroom apartment rents for $2,369 a month. To afford this without being rent-burdened would require an annual income of more than $105,000. But because Boston wages haven’t kept pace with rents, the Boston Foundation’s Housing Report Card shows, 51 percent of Greater Boston renters now qualify as rent-burdened.

The consequences have been devastating. A wave of evictions—mostly for nonpayment—has swept through the region, intensifying after mid-2021 when COVID-era protections expired and federal rental assistance ran dry. State eviction filings now average 3,000 a month, up more than 15 percent from pre-pandemic levels, according to Matija Jankovic, a senior research analyst at the Massachusetts Housing Partnership. Predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, in particular, have experienced the heaviest burden as evictions continue to climb.

Meanwhile, the final stage of eviction—physical removal from a home—affected more than 11,000 households in 2023, with numbers increasing steadily since the pandemic and on track to be higher this year than last. And this is an especially devastating period for evictions, Jankovic notes, as the current housing market’s complexity and challenging conditions make it extraordinarily difficult for displaced residents to secure new homes.

Harvard Legal Aid Bureau faculty director Eloise Lawrence and her law students offer free legal counsel to tenants facing eviction. / Photo by Tony Luong

The crisis has also taken an unexpected turn: Evictions once primarily affected those who’d lost jobs or lived on fixed incomes or disability. Now they’re hitting the fully employed. “I’m meeting people who say, ‘I’m working full time or I’m working two jobs, and I cannot afford the rent.’ That’s pretty extraordinary,” says Eloise Lawrence, faculty director of the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, which provides pro bono legal representation to tenants in housing court. “Traditionally, working-class people have been able to live in Boston and keep a roof over their head. That doesn’t exist anymore.”

And that, it turns out, is a big problem for everyone, as the exodus of essential workers threatens the city’s very foundation. “Boston runs because of service-sector workers, and it’s not just people who work in restaurants and office buildings—it’s teachers, people taking care of our children, our elders,” says Andrea Park, director of community-driven advocacy at the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute. “We have these world-class hospitals and institutions, and there are a lot of people employed there who are not able to afford living in the city. And that is dangerous for all of us.”

Annie Gordon is battling to stay in the home she has lived in for a half century after her corporate landlord raised the rent by $300 a month. / Photo by Tony Luong

Annie Gordon stands in her apartment on a warm fall day, gazing at the place she’s called home for the past half-century. By the balcony’s sliding glass door, she gestures to where she and her son had decorated their Christmas tree each year. Her eyes drift to the small kitchen, now overrun with mice, where she’d baked the sweet-potato pies his friends would devour. “After all these years, it has become a home,” she says, sighing. “I had thought maybe this was my forever home.”

That is no longer looking likely, as Gordon is engaged in a difficult battle with the landlords of the only home she’s ever known as an adult. For nearly five decades, she managed to keep pace with rent increases at Fairlawn Apartments, a roughly 350-unit Mattapan complex catering to low-income residents and Section 8 voucher holders. But everything changed in 2018 when DSF Group, a national real estate firm headquartered on Newbury Street, purchased the property for $65 million. The company promptly hiked Gordon’s $1,810 rent by $300—a more than 16 percent jump—while some tenants saw increases as high as 50 percent, according to City Life. The only improvement, Gordon notes, was an electrical system upgrade. Already working part-time at Walmart at age 73 just to afford her current rent, she saw no way forward. (DSF Group did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

The story of Fairlawn Apartments illustrates a key force behind the eviction crisis. Research from the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) reveals that investors, not homeowners, were behind 20 percent of Greater Boston’s housing purchases between 2004 and 2019. This surge in investor buying accelerated during the 2008 foreclosure crisis when properties—especially in hardest-hit communities of color—were selling at fire-sale prices. The government research agency also found that investors focused particularly on densely populated, low-income neighborhoods, areas that predominantly house renters and people of color.

Over time, housing in Boston has transformed from basic shelter and local business into a lucrative investment commodity.

Over time, housing in Boston has transformed from basic shelter and local business into a lucrative investment commodity. According to the council’s research, investors who recently acquired properties in the Greater Boston area have raised rents as much as 70 percent. Some justify these increases with renovations, while others simply capitalize on the tight housing market to charge more for unchanged properties. Meanwhile, many new owners either refuse to renew existing leases or they issue no-fault evictions, a type of eviction in which the landlord doesn’t have to demonstrate cause, clearing the way for tenants who can pay more. And owners of small multi-family buildings frequently clear out existing tenants before selling, knowing that vacant properties attract more investors.

Steve Meacham, organizing coordinator at City Life, says Boston-area tenants are facing a current barrage of no-fault evictions, the most he’s seen during his 25 years at the organization. “I’m working with six tenant associations in the suburbs, all of which are facing mass evictions as a result of no-fault,” he says. “If you get a big rent increase and you can’t afford it, then the type of eviction that allows the landlord to evict is no fault. That is the engine of displacement.”

The steep rent hikes at Gordon’s complex struck a particularly raw nerve in the housing rights community. For two decades, Mattapan community members and leaders had battled to secure a Fairmount Line commuter-rail stop, finally winning that hard-fought victory. But just as the new station was set to open, DSF purchased the property, rebranding it as “SoMa at the T”—a hipster nod to South Mattapan that locals rejected. “When the community finally got the public investment in a commuter-rail stop, investors immediately swooped in to capitalize—using the community’s efforts to make profits for themselves and hurting the very people who made the commuter-rail stop happen,” says Gabrielle René, City Life’s Mattapan organizer.

City Life sprang into action when Fairlawn residents learned of their rent hikes. The organization deployed its signature “sword and shield” strategy, with organizers helping tenants form a union and craft a public letter to management. In it they petitioned for negotiations on the new leases, laying out clear demands: better living conditions, annual rent increases limited to 2 percent, and extended lease terms for more stability. As part of the “sword,” City Life and union members staged protests, including one outside a Rhode Island theater where DSF’s CEO sits on the board of trustees.

City Life also educated residents about their tenant rights, advising them to maintain their current rent payments without signing new leases, since they couldn’t be forced into increases to which they never agreed. The landlord responded by informing tenants who did not sign leases that they would not only face the initial monthly increase, but an additional $500, too, according to City Life. This caused many long-term residents to scatter, some leaving Boston entirely. In October 2023, management began eviction proceedings against the holdouts, including Gordon and Betty Lewis, a 73-year-old woman who has lived there for 40 years.

Betty Lewis prepares to move before her eviction hearing. / Photo by Tony Luong

Through City Life’s pro bono legal aid—what the organization calls its “shield”—both women have managed to stay in their homes. But by this September, Gordon and Lewis said their battle was looking like one they could not win and had begun packing up their belongings. “I try to keep from crying, but it’s a hard thing to have to pack up from where you live. I never had to do this. I’ve never been evicted from my home. You should be able to stay in your home without people gouging you,” says Lewis, who shares her apartment with her adult daughter to be able to afford it. “They’re asking us to pay all this money. We do not have that kind of money. We’re just trying to survive in this big, fast world of ours.”

What happened at Fairlawn reflects a daily reality across the city—one that housing advocates say should push all Bostonians to reimagine how we think about housing, perhaps treating it like other essential resources during times of scarcity. “When there’s a hurricane or a flood or a tornado, and someone comes along and charges $100 for a gallon of water, we say it’s illegal price gouging. We say that’s immoral,” Harvard’s Eloise Lawrence says. “We don’t say that with housing. We say, ‘Well, it’s just the market.’ You can charge more because people are desperate for it, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we should allow it.”

One way to stem runaway rents is through rent control, a controversial tool that was abolished statewide by voters via a ballot initiative in 1994 following years of limited success. Just last year, Boston sent a home-rule petition to the state legislature that would limit annual rent increases to either 6 percent plus the consumer price index change or 10 percent, whichever is lower, while also prohibiting evictions without cause. Somerville and Brookline followed suit with similar tenant protection proposals.

Housing advocates are pushing for another reform: the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA), which would grant tenants the first chance to buy their homes when they go up for sale, provided they can match outside offers. Under TOPA, residents could either combine their resources or transfer their purchase rights to a nonprofit or housing authority, which would maintain affordable rents long-term. Though lawmakers excluded TOPA from the August housing bill, its impact—had it been law years ago—could have been transformative for Fairlawn. Back then, a nonprofit matched DSF’s offer but was rejected. (Oftentimes, property owners prefer to sell to private investors, not nonprofits, because they can pay cash or secure financing faster.) Had TOPA been law when Gordon and Lewis’s building was up for sale, they wouldn’t be facing the loss of their homes today.

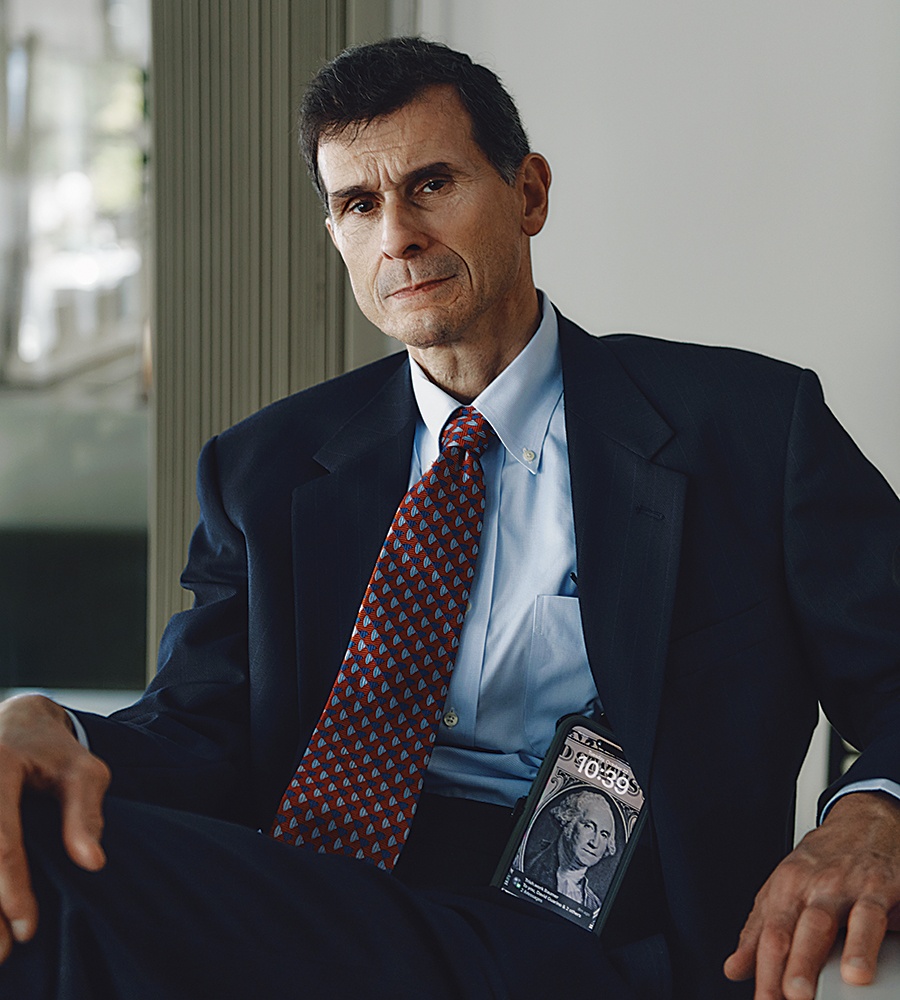

Greg Vasil, CEO of the Greater Boston Real Estate Board, says a severe housing shortage is the culprit behind Boston’s sky-high rents. / Photo by Tony Luong

Every Thursday, a tide of tenants floods the fifth floor of the New Chardon Street courthouse as the Eastern Housing Court springs to life. One morning this fall, a property owner’s attorney wheeled her briefcase down the hallway toward the courtroom, preparing to argue that a tenant facing eviction in her client’s building had accumulated $38,000 in unpaid rent.

That sum would stagger any business owner. According to Greg Vasil, who heads the Greater Boston Real Estate Board representing major property owners, landlords often bear the financial burden when tenants leverage protective laws and the state’s emergency eviction prevention program. The application process for these funds can delay evictions for months, says Vasil, whose organization’s members include large out-of-state corporations. “At the end of the pandemic we had a member who had a renter at the Pru who was not paying their rent, and had run up a bill for like $70,000,” he says. “It was absurd, but they knew they could get away with it in the court system.”

Doug Quattrochi, the executive director of MassLandlords, a trade association for landlords of small buildings, agrees. “There’s no doubt that Massachusetts is one of the safest places to be a renter in the country,” he says, adding that if you are a renter and get an eviction notice and are taken to court, “the odds are good that you’re going to end up with a mediated payment plan. You have at least a 78 percent chance of avoiding eviction.”

While housing advocates point to landlord greed, industry representatives see a simpler explanation for soaring rents: basic supply and demand.

While housing advocates point to landlord greed, industry representatives see a simpler explanation for Massachusetts’ soaring rents: basic supply and demand in a state starved for housing. And it’s not just real estate prices that are more expensive than ever, Vasil notes. “The cost of everything has gone crazy,” he says. “People forget that the price of insurance has gone absolutely through the roof. You have to look at the building’s costs, what it costs to get a plumber out there.”

The only way to ease the crisis, real estate industry pros maintain, is to build more multi-family housing. Data reinforces this position, showing a severe housing shortage across Massachusetts. According to the MAPC’s analysis of 2020 census information, the Greater Boston region—spanning 101 cities and towns primarily within I-495—needs more than 16,700 rental units to reach a healthy vacancy rate of 7.4 percent. The shortage extends beyond Greater Boston, with a statewide rental deficit of more than 30,700 units. Looking ahead, state projections indicate Massachusetts will need 200,000 additional housing units—both rental and owner-occupied—by 2030 to keep pace with demand.

While Boston, Somerville, and Cambridge have done a relatively good job of adding housing stock, surrounding communities must play a larger role in solving the crisis by building more multi-family homes. The problem? Many towns near Boston resist changing their zoning laws to allow such development, arguing it would alter their community’s character. In fact, resistance runs so deep that some towns are testing the limits of the MBTA Communities Law, which requires communities with T service to designate at least one district for multi-family housing. This defiance prompted Attorney General Andrea Campbell to take legal action, suing Milton in February over its refusal to comply.

Organizers advocating for protections for renters. / Photo by Matt Stone/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald

What landlords don’t believe will solve the problem is rent control, pointing to Massachusetts’ previous flawed experiment with it as a cautionary tale. During its run from the 1970s through its abolition in 1994, opponents argue, the policy backfired. They cite how 30 percent of rent-controlled units went to higher-income tenants—including, famously, the prince of Denmark and the mayor of Cambridge. Critics also blame the policy for shrinking the rental market as property owners abandoned the real estate business, while remaining units suffered from neglect. Looking ahead, Vasil sees little reason for optimism about rent control’s prospects. “It is a disincentive to produce,” he says. “Our biggest owners are our market-rate owners. They’re always asking me, ‘How close is rent control to Massachusetts? Because we will exit the market when it passes.’”

TOPA presents another challenge, landlords argue, by lengthening the property sale process. When tenants or nonprofits attempt to purchase buildings, securing funding takes time—especially for nonprofits, which often combine government support, philanthropic donations, and traditional financing. According to a 2023 housing report from the MAPC, sellers prefer cash payments so much that they will sometimes accept lower amounts over higher bids that require financing.

At the same time, the report found, TOPA also scares investors off. “No one in the private market will shop in a TOPA town,” Quattrochi says. “If Cambridge or Boston adopted it, people wouldn’t shop there for investments, because they couldn’t close for 180 days, and they might not even close after that, once the nonprofits get involved.”

So far, the landlords’ concerns and lobby efforts have prevailed: State legislators stripped TOPA from the housing bill Governor Maura Healey signed in August, while rent control measures have failed to gain traction. Yet amid their disagreements, housing activists and landlords share one clear understanding: Boston’s soaring housing costs are increasingly pushing out the working-class residents vital to the city’s economy. “It is a big issue, one [our industry] deals with every day,” Vasil says. “Everyone is dealing with the problem of finding help.”

Tenants facing eviction await their turn at housing court in Boston. / Photo by Pat Greenhouse/the Boston

The whine of a buzz saw and staccato bursts from a nail gun echo through Yvette Moore’s home in Dorchester, now a full-on construction zone. As she weaves her small frame between workers and tools, the scent of sawdust and paint hangs in the air as electricians install a kitchen hood and a worker hangs tile in the bathroom.

This is Moore’s home, transformed. No longer will black mold exacerbate her asthma, raccoons breach the back porch to nest in her walls, or mice skitter across her floors. But the most profound change isn’t physical—it’s the peace of mind knowing that no landlord can ever price her out or threaten eviction. For Moore and her next-door neighbor, Shaunda Henderson, this two-family home’s conversion to permanently affordable housing was nothing short of winning the lottery.

Their fortuitous journey started in 2022, when their landlord announced plans to sell the building, and Realtors began showing both Moore’s and Henderson’s apartments. Both women were terrified of ending up on the street. Finding new housing in Boston seemed nearly impossible—especially since both rely on Section 8 vouchers, federal rental assistance that is falling increasingly short of the city’s soaring market rates. “Vouchers have a rent cap, and units have gotten so expensive that voucher holders can’t use them,” says the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute’s Andrea Park. “The most heartbreaking thing is to see someone who’s waited years for a voucher be unable to use it.”

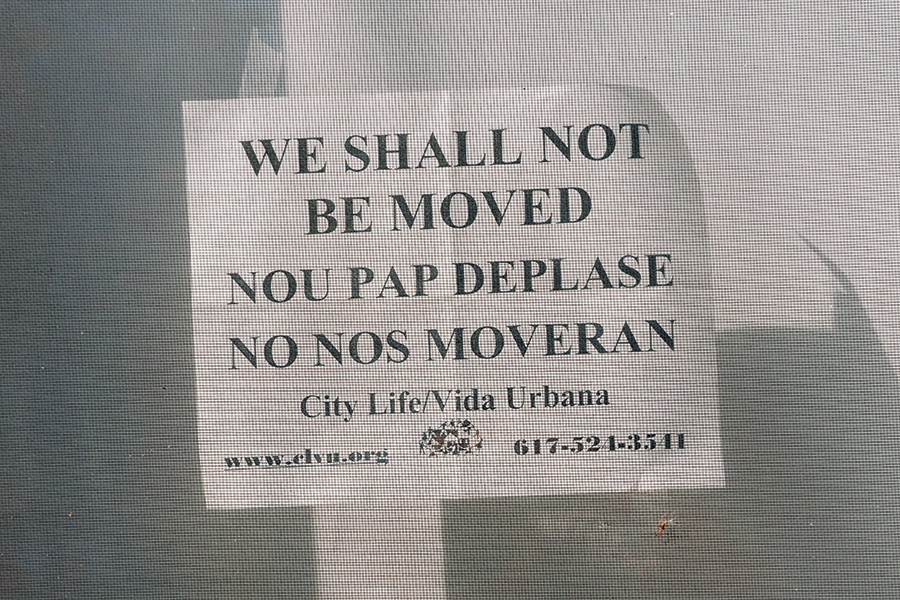

City Life/Vida Urbana supplies these tenants with window signs, like the one displayed in Lewis’s window. / Photo by Tony Luong

But Moore and Henderson found a lifeline in City Life/Vida Urbana. The organization armed them with “We Shall Not Be Moved” signs, which they displayed prominently during real estate showings—a clear message to potential buyers that the tenants wouldn’t leave without a fight. The group also connected them with legal representation.

Most important, City Life organizers completed their strategy—after the “sword” of protest and the “shield” of legal aid—with the offer. They introduced Moore and Henderson to the Boston Neighborhood Community Land Trust, which grew out of a nonprofit City Life had helped establish. The trust’s mission: preserve affordable housing by purchasing properties at risk of being flipped on the speculative market and, in doing so, keep rents permanently accessible for existing tenants. “There needs to be a preservation strategy because we can’t just build ourselves out of the affordable housing crisis that we’re in,” says Meridith Levy, executive director of the land trust. “It’s great if we can build 30-unit buildings, but that’s not the only solution. We really need to think about how we can protect our existing buildings.”

After months of negotiations, using a combination of philanthropy, community development loans, and funding from the city of Boston, the trust acquired Moore and Henderson’s two-family home for $710,000, bringing its portfolio to 32 units in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan. Then came the renovations to transform the property into a safe, healthy living space.

City Life’s victories extend beyond taking properties off the market entirely. In East Boston, after nearly a year’s struggle in 2023, a tenant union secured three-year leases with rent increases capped at 3 percent and significant rent forgiveness. In an even more remarkable case, a Honduran grandmother in Chelsea—who had successfully fought off six eviction attempts since 2009 with City Life’s legal support—secured a six-year lease earlier this year with annual increases limited to 5 percent.

Still, success stories remain relatively rare. After her eviction, Noreli Vasquez—the East Boston resident whose husband’s illness upended her life—drifted between temporary housing arrangements, unable to find permanent housing in her neighborhood, before landing in Revere. Now she shares a three-bedroom apartment with two strangers, paying $1,000 of the $3,000 monthly rent. Though the burden is lighter than her previous rent, it’s still crushing enough that she’s hunting for part-time work to supplement her full-time job. Her daily commute, once a two-hour round trip, now stretches to three hours.

Annie Gordon. / Photo by Tony Luong

Meanwhile, over at the Fairlawn Apartments, Betty Lewis is gearing up for a spring mediation session with the landlord’s attorney, her hopes for negotiating a smaller rent increase fading. Annie Gordon, who faced an eviction for failing to sign the new lease and for allegedly being rude to a representative of the property management company, won a jury trial in late October, but says her attorney warned her that she can likely expect a new eviction for non-payment of rent. Meanwhile, DSF has listed the building for sale, attracting interest from a local nonprofit. However, without TOPA protections, the organization has no guaranteed right to match competing offers, even if it could afford to do so. The timeline for any potential sale offers little comfort to Lewis and Gordon. For now, they’re simply trying to buy more time to find new homes while working with a representative from City Hall to secure affordable housing.

After a five-year fight, these elderly women—already wrestling with health problems—are finally reaching their breaking point. “The fight takes a toll on you mentally, physically, and spiritually,” Lewis says. “I have to have a place to live, and if I have to go broke, or go hungry, or go without my medication to live in a place, I guess that’s what I have to do because I do not want to be another homeless person on the street. I just want to be in a home where I’m happy for my last days, where I can sit down, look across the living room, and just breathe.”

A version of this guide was first published in print edition of the December 2024/ January 2025 issue, with the headline “Home Sweet Home?”