How to Live Long and Prosper, According to Overachievers Living Longer

Keep busy. Stay social. Do purposeful work. In America’s longevity capital, five elder Bostonians share how not only to add years to your life, but life to your years.

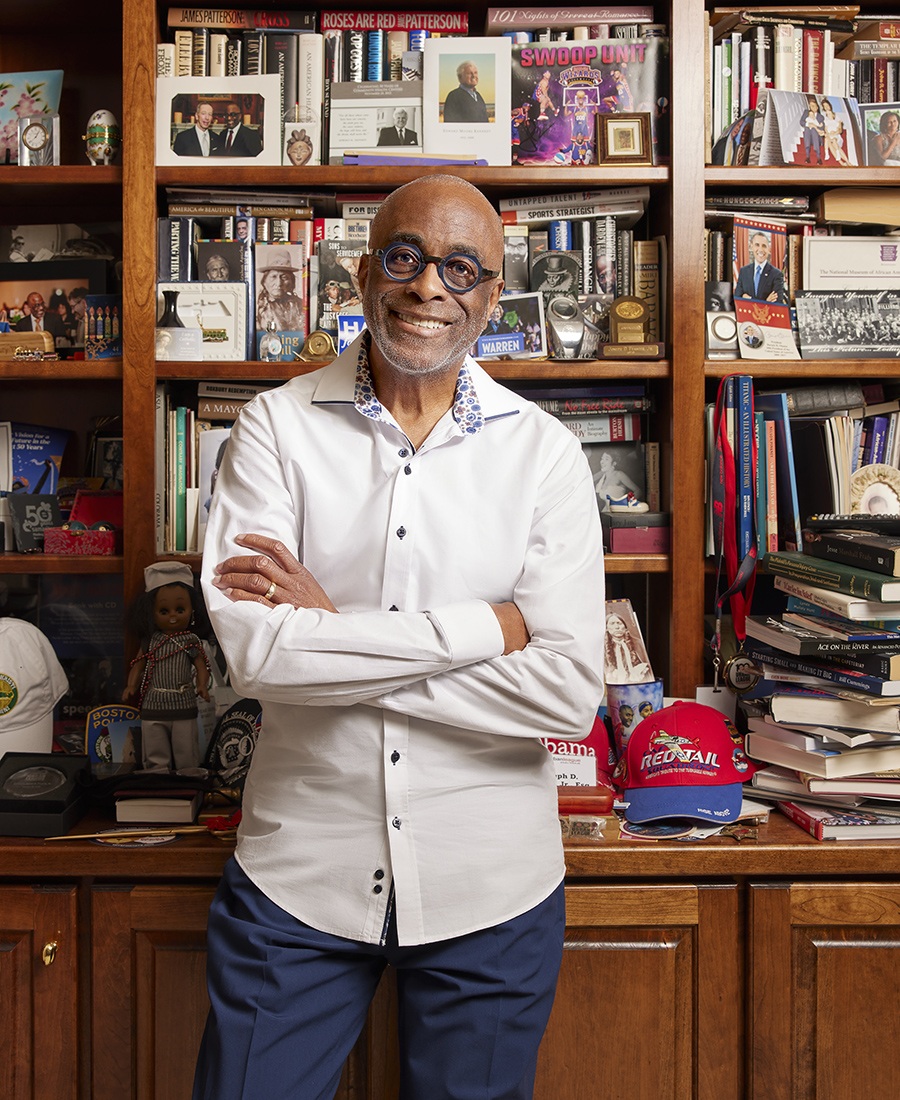

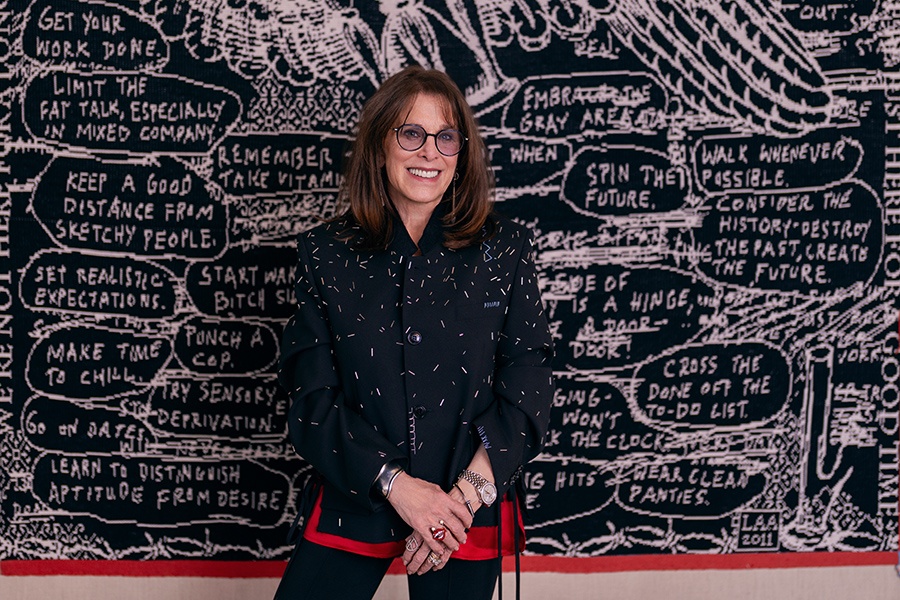

Clockwise from top left: community organizer Shirley Shillingford; real estate mentor Kevin Phelan; Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin; attorney Joseph Feaster Jr. / Portraits by Ken Richardson

Earlier this year, we went looking for Boston’s ageless wonders, those incredible folks who prove birthdays are just numbers on a calendar, not expiration dates. What we found were five Bostonians who’ve mastered the art of vibrant aging in their own distinctive ways. From Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s seven-day work weeks at 82 to Joseph Feaster Jr.’s dedication to mental health advocacy at 75; from Kevin Phelan’s entrepreneurial spirit at 80 to Shirley Shillingford’s community-first approach at 82; and Barbara Cole Lee’s contemporary art adventures at 75—each offers unique wisdom about living fully at any age.

What connects these remarkable individuals isn’t just their Boston roots but their shared secrets for longevity: purposeful work, strong social connections, continuous learning, spiritual grounding, and the courage to embrace new challenges when most of their peers have long settled into retirement. Their stories aren’t just inspiring—they’re instructive.

Portrait by Ken Richardson

Doris Kearns Goodwin

Historian, Author, and Film and TV Producer

Age: 82

Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin is at the Rancho Mirage Writers Festival on a Sunday (one of the seven days a week she works) and is toggling between putting the final touches on her upcoming History Channel American West docuseries with Kevin Costner and prepping for her on-stage interview with Bill Gates the following night.

For someone who’s built a career on looking back, the Boston resident sure spends a lot of her time moving forward, logging upward of 80 days a year on the road. “I just love what I’ve been doing for my whole life. I love history, and I keep learning more about it because I want more people to love it,” says Kearns Goodwin of her enthusiasm for new projects, like the FDR docuseries she coproduced with Bradley Cooper in 2023. “As long as I can keep working on history in different forms, it gives me a sense of purpose waking up every day.”

Kearns Goodwin characterizes herself as “far more social than a writer would normally be,” which was certainly a benefit during her 100-plus stops on two book tours last year promoting both her young-adult offering, The Leadership Journey: How Four Kids Became President, and Best of Boston winner An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the ’60s, her paean to both her late husband, Dick Goodwin, and the tumultuous decade during which he served as a senior adviser to JFK, LBJ (for whom Doris also worked), and RFK. But being off the road by no means curbs her desire to socialize: She has a standing weekly confab with a group of Boston’s female power players at the ’Quin House, and within her neighborhood enjoys more impromptu get-togethers (with wine!) that she dubs sundowners—because, justifiably, at any hour the sun is setting somewhere.

Kearns Goodwin explains that since her husband passed, she no longer has her in-house editor but now relishes her creative partnership with Beth Laski, with whom she runs her production company, Pastimes Productions. “I have a great routine,” she says. “I wake up at 5:30 in the morning, and then I’ve got until noon to write, because Beth lives on the West Coast. Then, at noon, I can do all the other projects Beth and I do together, including the series and documentaries. It’s been wonderful.”

This, of course, is not Kearns Goodwin’s first foray into Hollywood. Her book Team of Rivals was the basis for Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln. “Beth and I learned together what it means to be executive producers, getting involved every step of the way: working on early scripts and outlines, talking to the actors, going over the dailies, editing and music.” She also played herself in both American Horror Story, and on an episode of The Simpsons.

Nor will it be her last: Tom Hanks and Barbara Broccoli (James Bond) recently acquired the screen rights to An Unfinished Love Story, the aforementioned book about her late husband that debuted at the top of the New York Times bestseller list. The film will be coproduced by Pastimes Productions.

The death of Kearns Goodwin’s husband was also the impetus to relocate from their longtime home in Concord, where they raised their three sons, to Boston. Now, she’s a mere elevator ride away from one of those sons and his family. “It’s a real sense of community,” she says, describing the close relationships she has developed with her neighbors and building staff.

In fact, Kearns Goodwin shows no signs of slowing down from her busy schedule of speaking engagements, television appearances, university lectures, film producing, and, of course, writing history. “It’s kind of crazy,” she says. “There are times I’m walking through the airport dragging my suitcase around with my big heavy bag in my left hand, and I say, ‘What am I doing?’ But I wouldn’t change it. As long as I can do it, I’ll keep doing it.”

Portrait by Ken Richardson

Joseph Feaster Jr.

Counsel, Dain Torpy

Age: 75

Despite his towering legacy as a prominent Boston attorney, Joseph Feaster Jr. points to a transformative experience beyond the courtroom—a trip to Israel with the late civil rights leader Lenny Zakim, with whom he previously chaired the Greater Boston Civil Rights Coalition. “We met with Ethiopian Jews, traveled through the Golan Heights, I stayed in a kibbutz. I was in Nazareth, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, at the Wailing Wall.” The journey led to what he calls “a religious experience.”

Though raised Catholic, Feaster and his wife, Phyllis, found themselves drawn to Mattapan’s Morning Star Baptist Church after his return. Under Bishop John Borders III, who remains pastor to this day, Feaster took a decisive step on Palm Sunday 1985. “I walked up and got baptized,” he says, “and I’ve been a member ever since.”

This dedication to community began when the Bronx native accepted a scholarship to Northeastern’s inaugural criminal-justice class in 1967. “I didn’t know anything about Massachusetts. But with the offer they had…” Feaster recalls of his decision to make Boston home. After graduating from Northeastern’s law school, he embarked on two decades in public service, followed by 24 years at McKenzie and Associates, a Black-owned law firm that enabled his continued community involvement. During this time, he also served as interim administrator of the Boston Housing Authority, chaired the Board of Appeals, and acted as town manager of Stoughton.

From his home office in Stoughton, Feaster is experiencing a rare moment of quiet when we chat: He’s recovering from minor surgery under the watchful eye of his wife, a former teacher whom he playfully dubs “Dr. Phyllis Feaster.” With characteristic precision, he assures me they didn’t operate on his mouth—he’s ready to talk. “I guess it’s the lawyer in me that wants to start from the beginning,” he says. It’s also the lawyer in him that gives me verbal consent to record our conversation, before I’ve even had the chance to ask. It’s become rapidly clear that you can take Feaster out of the law office, but you can’t take the law out of Feaster.

Now counsel for the law firm Dain Torpy, Feaster continues to generously give his time and expertise to many organizations, including Home Base, which provides free clinical care for veterans. “When I serve on anything, I give 110 percent. My thing is that I’m not going to serve without serving,” he says. Following personal tragedy, he found new purpose in mental health advocacy through his work with Samaritans. “Because I lost my son to suicide, I am very committed. I consider that my ministry, anything having to do with mental health. In fact, I’ve established the Feaster Family Foundation to support organizations and individuals working with mental health and suicide.”

Even with his professional and community responsibilities, family remains central to Feaster’s daily life. “I speak to my daughter and grandson every day, no matter where I am in the world,” he says. “My grandson is 14 now, and I’m talking to him about what he expects from the day and what he did the day before. I give her fatherly advice, and I give him grandfatherly advice. And the only thing my grandson can say is, ‘Yes, Grandpa.’ So that’s how I start my day. Now, that’s after I’ve kissed my wife.”

Portrait by Ken Richardson

Kevin Phelan

Boston Office Cochairman, Colliers International

Age: 80

Kevin Phelan is in his pin-drop-quiet 100 Federal Street office on a Sunday morning—and that’s just the way he likes it. It allows him to “mop up one week and get ready for the next,” he explains. Naturally, he’s been in all five workdays the previous week. Later on, he’ll drive back to the home in Wellesley where he and his wife, Anne, lived for 42 years before she died in 2023. By 6 the following morning, he’ll be driving back into the office to work on his next major real estate financing deal.

He raises the topic of his wife’s passing very early in our conversation as he ticks off a list of friends/contemporaries/business leaders in their eighties who are “still in the game.” He then thoughtfully mulls the question of why he still works as hard as he does at 80 and, more important, having achieved financial success, why he still enjoys it more than he would retirement, as the choice is clearly his. He mentions his partner, Tom Hynes, along with other notable Boston business leaders, as he wonders aloud whether being widowed could be the motivation to continue working.

But it also seems to occur to Phelan, a tall, soft-spoken man dressed casually in khakis, a sweater, and Hoka running shoes, that despite the fact that many of those people are affiliated with larger corporations, they are all essentially entrepreneurs. “Real corporate guys pension out or are pushed out because [corporations] want to move the next generation up. Whereas the entrepreneur, he or she might have reasons to stay in the race, and they’re all also active civically. I’m on too many boards.” Phelan speaks the truth—there are more than a few dozen past and present charitable and corporate board affiliations listed in his Colliers bio.

Then there’s the mentoring factor: Phelan lights up when he talks about it. “I love working with kids, helping them get into college or giving them advice on how to find jobs,” he says. “Just last Saturday, I sat in a parking lot for 25 minutes with the son of a downtown colleague who wants to get into real estate.”

It was that spirit that inspired him and several of his contemporaries to launch the Breakfast Group in 1976, an ongoing club of which he is both director and its only remaining original member. The Breakfast Group still retains its original mission of connecting leaders from a wide variety of sectors while focusing on job creation, regional economic development, and mentoring the next generation, which, after 49 years of operation, includes multiple “next” generations.

As a proud Providence College alum, Phelan fondly recalls his college days, where he first bonded with lifelong friend and star basketball player Ray Flynn, who later became Boston mayor. Additionally, he advises the Archdiocese of Boston on financial and real estate matters, including spearheading a $26 million dollar “cleanup” of the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, where seven of his grandchildren were baptized, in 2018

and 2019.

Having fundamentally changed an entire neighborhood within the South End by financing the Ink Block development over the past decade, Phelan is currently focused on projects in West Hartford, Newport, and the rapidly evolving city of Worcester. But, in his own words, “When the great book is written, it’s not about the corporate deals I was involved in. I grew up in a Boys & Girls Club where I’m from in Connecticut, and when I was able to, along with then-Mayor Flynn, I helped build the Boys & Girls Club on Blue Hill Avenue and Talbot—that’s the deal I’m most proud of.”

Portrait by Ken Richardson

Shirley Shillingford

President, Caribbean American Carnival Association of Boston, and founder/manager, Shirley’s Pantry

Age: 82

Shirley Shillingford lives by a single saying: “Do all the good you can to all the people you can in all the ways you can, just as long as you can.” Adoringly known as “Miss Shirley,” she’s taken that calling for service to heart, marking her golden anniversary working for the city of Boston across six mayoral administrations while simultaneously running the Caribbean American Carnival Association for 34 years and a vital food pantry for 33.

That food pantry’s origin story showcases Shillingford’s quiet determination. Started in the basement of a municipal building in Hyde Park before moving to Mattapan, it began without any backing. “At that time we had no one supporting us, not even public health,” she says. “We got private people to support the pantry, and over time, the politicians saw the need for it and supported the pantry. That was 1992, and here we are now.”

Her persistence paid off. In December 2019, then-Mayor Marty Walsh officially christened the space “Shirley’s Pantry”—making official what locals had long called it. “I am completely grateful to him,” Shillingford says. “Not many people see the work you do and recognize it. So when he named the pantry after me, although it was an absolute surprise, it was wonderful and emotional for me. At my age, I’m grateful, as they say, that they give you your flowers while you’re alive.”

What started as a simple food distribution center has evolved under Shillingford’s guidance into a comprehensive community hub, offering free clothing and daily meals at its River Street site. The pantry also hosts an annual turkey giveaway event, distributing 400 holiday meals to elderly residents and families in need. “I also put on a senior citizens ball,” Shillingford adds, noting that she personally cooks for the formal dinner dance. “We find that seniors have paid their dues in the world,” she says, “so we need to recognize them and offer them something to make them know they are very special.”

At the same time, this busy senior makes time to care for herself, too. Her exercise routine, she explains, consists of “walking up and down in the pantry daily,” and she doesn’t drink or consume a lot of sugar. But the secret to her longevity, she believes, is doing “a lot of reading and puzzles”—and staying centered. “I don’t entertain stress from things or people,” she notes. “Stress is very toxic if you allow people to rent space in your brain.”

What does take up space in her brain, however, is her work with the community. As president of the Caribbean American Carnival Association, Shillingford orchestrates a weeklong celebration of Caribbean culture each August. The festival culminates in an all-day party beginning with a J’ouvert (or daybreak) celebration, followed by “the big parade.” As Shillingford animatedly describes it, “We have the giant costumes like you would see in Brazil or Trinidad, and they compete in different categories—king, queen, [best costume] individual male, individual female, band

of the year.”

When asked where she gets the energy to lead all of these endeavors, she looks upward and tells me, “You are a young person who looks at people my age and sees how active we are. We didn’t do it alone. God has been an influence in our lives and gives us the energy and the wherewithal to work and make a difference in people’s lives.”

Portrait by Ken Richardson

Barbara Cole Lee

Contemporary Art Collector and Consultant

Age: 75 (this year)

There are ants marching across the floorboards and a chronic drip in the fireplace at Barbara Cole Lee’s Brookline home, but rather than call an exterminator or a plumber to address these issues, she called a gallerist to have these video art pieces installed. It’s all part of the endless pursuit of what’s next in the world of contemporary art that keeps her young and moving forward.

Lee has always had a keen eye for contemporary art, and she credits her passion for the new for never giving up on her quest; like Doris Kearns Goodwin, she still loves learning. “Are you familiar with Marilyn Minter?” asks Lee, pointing out another work of art in her own collection. “She did that video piece—it’s somebody licking pearls in their mouth, and you’re mesmerized. It both repels you and attracts you.”

Lee isn’t just a significant collector, though: She’s made a career of working as an art consultant. “I love art consulting. I love helping people buy what they love,” says Lee of why she’s still doing it into her mid-seventies. A former longtime board member of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, she says she honed her sales skills overseeing and modernizing its famed annual art sale. But she never imposes her aesthetic on clients, she says—rather, “I let them tell me what they like.” She explains that the longer she works with people, the more intuitive their interactions become, adding, “Once I’ve got the go-ahead, I’m scouring the Internet, going to galleries I’m familiar with, or looking at artists’ websites to find what’s available. Once I’ve identified something, it’s a quick motion, because art is fluid, and what you like today may not be available tomorrow.”

As most people age, their tastes get more traditional. Not Lee. “I think as you get older, you are more willing to take risks. I don’t need one of the blue-chip artists, because I want to support emerging artists, and the things that are appealing to me are the things that make me think, make me feel, make me want to watch, make me want to look.” When I slip and ask her a question about her pursuit of modern art, she is quick to gently correct me. “Modern art is really from the ’50s and ’60s; contemporary art is from the ’70s and ’80s to the 2000s.” It’s then that I understand another inherent quality that endears her to her clients: Discussing art can be intimidating, and Lee lacks any trace of condescension.

Lee’s verve and energy are innate, but she lets us know that they are coupled with a serious health regimen that she sticks to regardless of whether she’s in Boston, her mountain home in Aspen, or elsewhere. “I’ve been a vegetarian for more than 20 years,” she says, limiting herself to two meals a day and always eating dinner before 6:30 p.m. She emphasizes the importance of hydration and stretching before doing Pilates three times a week and augmenting that with two to three weekly treadmill sessions. But her biggest keys to long-term vitality? Having a strong social network—and good genes. “My parents died at 94 (mother) and 97 (father), and my father ate every kind of crappy food you can imagine,” Lee says. “He loved Kentucky Fried Chicken, and he did not die of heart disease or cancer.”

This piece was first published as part of a print package in the April 2025 issue with the headline: “Live Long and Prosper.”