Does Boston Need a Gun Buyback Program?

Photo via Jed Hresko on Flickr.com/Boston’s 2006 Gun Buy Back

As the community grapples with a sharp increase in gun-related deaths, officials are scratching their heads trying to figure out a solution that could help put an end to the violence. And while the Boston Police say they can’t “arrest the problem [of shootings in the city] away,” others believe they can quell the increase in crimes with a gun buyback program.

“When are we going to say enough is enough? I’m 50 years old, and I got a 14-year-old, and I worry what’s going to happen to him. If I was a prosecutor, my evidence that something ain’t working would be [the latest crime statistics]. Something isn’t working,” said James Thompson, during a community meeting hosted by Boston City Councilors on Wednesday night at the Hibernian Hall on Dudley Street in Roxbury.

Thompson and many other residents, as well as anti-gun advocacy groups, stood before City Councilors and police officials at a podium and discussed ways to get guns off of the streets, and instead offer alternatives to violence and gang activity.

Police blamed the gun-related deaths this year on a multitude of factors, such as ongoing gang feuds, arguments over statements gang members post about one another on social media, and late-night parties held in abandoned houses that lead to fights and large arguments. “These kids are saying ‘I’ll come on your turf and post it on Facebook and YouTube,’ and some of our youth take issue with that and pick up a gun. And instead of using conflict resolution, they use gun violence, and then there is retaliation,” said Boston Police Superintendent William Gross.

In the past year, shootings in the city between January 1, and June 10, have increased nearly 25 percent. Of the 104 people who have been impacted by gun violence in 2013, 17 have lost their lives, averaging nearly 30 percent more deaths from shootings compared with the same time period in 2012. That number went up in July.

When asked by city councilor members, police said it was tough to gauge why violence ebbs and flows over the years. They said sometimes it also depends on whether or not “main players” that incite gang rivalries are incarcerated or not. “[When in jail] they aren’t making a negative impact on the community, but another year everyone could be released, and the circle of violence starts again,” said Gross.

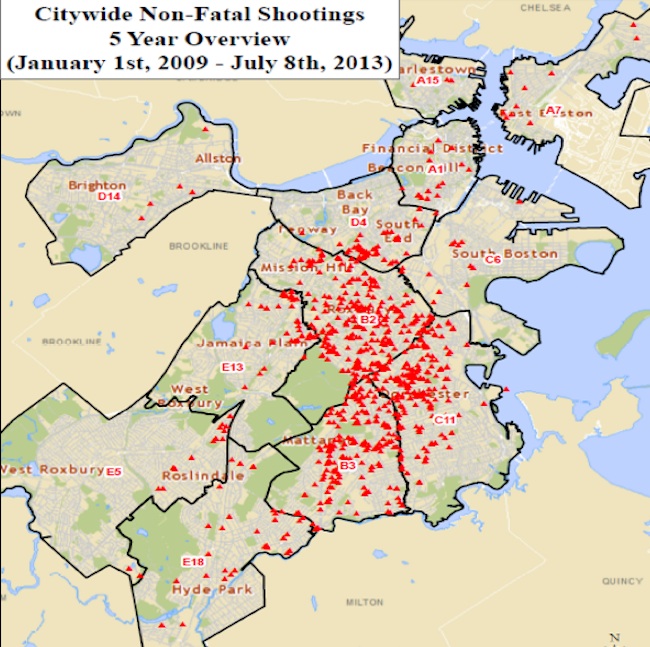

Police present at Wednesday’s hearing supplied a snapshot of the latest data, including heat maps that showed where the brunt of the non-fatal shootings are happening, and continue to happen year after year.

As a first step to stop the violence, City Councilors Mike Ross and Tito Jackson announced the formation of a Public Safety Working Group. It will be comprised of community partners and representatives from city agencies that meet biweekly. The first meeting will be held on August 5 at the Vine Street Community Center. “It’s the work that we do between these meetings that will really tackle this crisis. That’s why we’ve started this group, so that we can continue to bring people together, think up innovative solutions, and hold each other accountable,” said Ross, who serves as chairman of the Boston City Council’s Public Safety Committee and is a mayoral candidate.

But others called for additional methods of crime reduction, including a renewed look into a gun buyback program as a way to start getting illegal firearms out of the hands of gang members and the general public.

Police said many guns are coming from out of state and are being purchased in areas that have “lax gun laws.” This year, 359 guns have been taken off of the streets—321 of which were pistols—and most seem to have been stolen, police said.

Dain Perry, a resident of Charlestown and member of the Massachusetts Coalition to Prevent Gun Violence, said the city has done gun buybacks before, and several cities across the country are doing them now, multiple times a year, with great success. “Some people think it’s not worth doing, and that it doesn’t remove the firearms being used on the street—but removing a gun from the community is removing a gun from the community that may be stolen and used in anger. Many communities are finding it to be an approach to address violence in a very different way,” he said.

In 2006, the city, in conjunction with numerous community and faith-based organizations, ran a successful “no questions asked” buyback by offering anyone that turned in their illegal firearms a $200 gift certificate to Target stores. At the time of the campaign, Mayor Tom Menino said it “exceeded expectations,” and helped net 1,000 firearms.

Community activist and author Michael Patrick MacDonald ran a grassroots effort from 1993 to 1997, taking guns turned in by community members, which helped destroy over 2,900 firearms. He said that if the city officials consider doing one themselves, they should leave it to community organizers to put together, but offer their compliance and assistance. “I believe, though, that people in City Hall can’t do much to reduce violence other than being more open to grassroots leadership,” he said, adding that he met face-to-face with mothers of children and teens killed by gun violence in Boston during his program in the nineties.

MacDonald’s sentiment is something current grassroots organizations and anti-gun coalitions agree on, and it’s something that brought many of them to Wednesday’s meeting. “I know well the impact of violence,” said Thompson. “And when it happens, it’s the same rhetoric, over and over again. But this time something has to be done.”