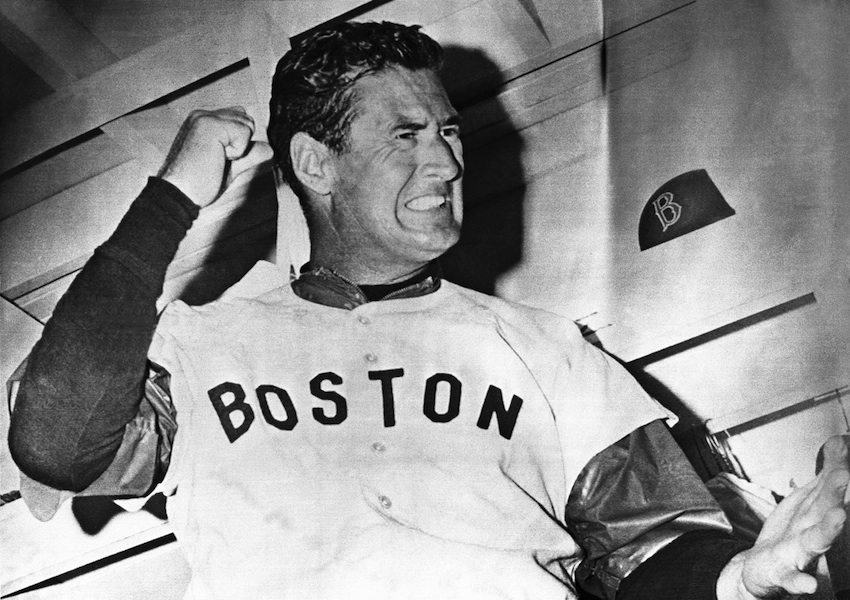

Throwback Thursday: The Time Ted Williams Spit at the Fenway Fans

August 8 marks the anniversary of the day that Ted Williams, whose relationship with fans was never easy, turned to the crowd at Fenway and spit at them.

Actually, he spit at them, walked into the dugout, then popped back out and spit at them again to be sure they got the point. It was 1956, and Williams had made an error in the 11th inning that spawned a chorus of boos from the crowd. When the jeers continued even after he made the catch that put an end to the inning, Williams lost his cool.

The gesture has become infamous, in part because it provides a dramatic example of his stormy relationship with fans and reporters, and in part because Manager Cronin fined him $5,000, a nearly unheard of penalty in those days. When discussing the fine, Cronin told reporters, “Ted was sorry he did it. He told me he didn’t know why he did it.”

Sensing that this sounded nothing like Williams, the reporters followed him to his hotel, where he gave them an interview through a closed door that presented a very different version of his contrition. The Boston Globe reported an (undoubtedly censored) version:

“I’d spit again at the same peopled who boohed me today,” Ted Williams said last night after learning of the $5,000 fine imposed on him by Sox owner Tom Yawkey.

Is Ted Williams considering quitting? Is this his last year?

“Probably …” he said.

Williams then repeated it to ensure reporters had gotten the quote right:

“Got it? … Read it back to me. I said boohing fans …”

Ironically, rather than push him into retirement, the incident actually marked something of a turning point for Williams and his attitude toward fans. There was a backlash against those who booed him. In his iconic New Yorker piece, John Updike defended The Spitting Kid:

The spitting incidents … should be judged against this background: the left-field stands at Fenway for twenty years have held a large number of customers who have bought their way in primarily for the privilege of showering abuse on Williams. Greatness necessarily attracts debunkers, but in Williams’ case the hostility has been systematic and unappeasable.

That week, others rushed to his defense, too. His biographer Leigh Montville writes:

A half dozen funds were started to pay his fine. A legislator from South Boston introduced a bill to have uncouth spectators at Fenway fined. Public reaction everywhere was on Williams’s side and against the side of the sportswriters, his persecutors.

Williams went to Baltimore the day after his fine, where fans cheered him raucously. According to Montville, Williams later recalled, “From ’56 on, I realized that people were for me. The writers had written that the fans should show me they didn’t want me, and I got the biggest ovation yet.”

He maintained his staunch dislike for the media, who he decided turned fans against him. But he returned to Fenway with a new faith that a perhaps less vocal majority had his back, all because of a very expensive bit of expectorating.