If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Best of Boston 2020: The COVID-19 Heroes Edition

In place of our annual Best of Boston reader's poll, we asked Bostonians to shine a spotlight on the everyday heroes in our city.

Portraits by Karin Dailey

Jump to:

Sheila Kennedy and J. Frano Violich

Portrait by Karin Dailey

Abhishek Gupta

Grocer, Kurkman’s Market

Most people aren’t on a first-name basis with their grocery store clerk—unless, that is, they shop at Kurkman’s Market.

“Kevin!” exclaims a gray-haired woman to the man behind the cash register at the corner grocery store in Brookline Village. Though their faces are half-covered by masks, squinting eyes exchange smiles of recognition before 32-year-old Abhishek Gupta—or Kevin, as he’s known to regulars—begins carefully bagging his customer’s fruits, veggies, and other items. When the woman finally scrubs her hands using alcohol-wipes provided at the checkout counter, Gupta, who manages many of the day-to-day operations at the store, walks the groceries outside into a sunny parking lot and puts them inside his patron’s car. She waves goodbye. See you soon.

This may look like a scene plucked straight from The Andy Griffith Show in the 1960s, but it’s just another day during COVID-19 for Gupta, who has become a beloved fixture and local hero for the way he’s kept his customers—especially the neighborhood’s many at-risk seniors—safe and supplied during this public health crisis. His secret? Personal service above and beyond the call of duty. Whether he’s spending hours assembling the detailed shopping lists he now allows customers to email him in advance, making local deliveries up until 10 p.m., or even letting loyal customers pay with an IOU, Gupta provides the rare human touch that’s hard to find during socially distant times—especially at an average chain supermarket. “Here, we feel like family,” Gupta says, standing outside the store for a welcome dose of fresh air. “It’s just like helping a friend out.”

Since the pandemic took hold, roughly 500 shoppers have come through the store’s doors each day—except Sunday, when the market is technically closed. Still, if a customer calls and Gupta is there, he’s happy to let them swing by. After all, it’s probably a familiar voice on the other end of the line. Gupta has memorized a Rolodex of shoppers’ names and favorite foods, and in fact, before he finishes assembling each emailed order—more like a personal shopper than a grocery clerk—he calls the customer to confirm their selections, discuss contact-free pickup and delivery options, offer alternatives for items out of stock, and, believe it or not, remind them of any favorites he’s noticed that they forgot to include. And if someone arrives and requests a last-minute addition? No worries—Gupta just tosses it in the bag and adds it to their next bill. Many regulars are allowed to keep charge accounts, an antiquated nicety that is hugely appreciated by shoppers, especially during the pandemic. Ultimately, he explains, “If you care for somebody, somebody will care for you back.”

The store’s warm, chummy “culture,” Gupta says, is one he set out to create when he started working there six years ago, not long after he immigrated to Boston from western India. Kurkman’s current owner, Harshad Patel, is from the same region of India and an old friend of Gupta’s father. From the start, Gupta took it upon himself to improve operations, beef up inventory (shortages have been minimal during the outbreak, he says), and modernize the century-old store’s systems. Now, there’s an app on his phone that can easily find the price of any item, Gupta says, scanning a box of hamburgers by way of example. He’s wearing sneakers and a bright-yellow snapback hat with a street-art-style graphic of a dog. “Rescues are my favorite breed,” it reads.

Gupta’s heroics are not easy, of course. Providing customers with so much individual attention requires time and energy—and like many essential workers who kept clocking in when the coronavirus first hit, Gupta was concerned about his health. Now, several months later, he still offers free masks to customers if they forgot their own and remains motivated by the smiles he receives when he arrives to shoppers’ homes with a week’s worth of groceries, especially seniors who are unable to make it to the market themselves. “Somebody’s hungry, and somebody’s waiting for me” is his daily mantra.

After putting the sacks of groceries into his customer’s car, Gupta walks back into the store through a sliding glass door. On it hangs a handmade sign from local children that is covered with notes. “We love you!” reads one. “Keeping us safe when we shop!” and “Always smiling!” read others. The largest one? It says it all: “Thank you.” —Scott Kearnan

Portrait by Karin Dailey

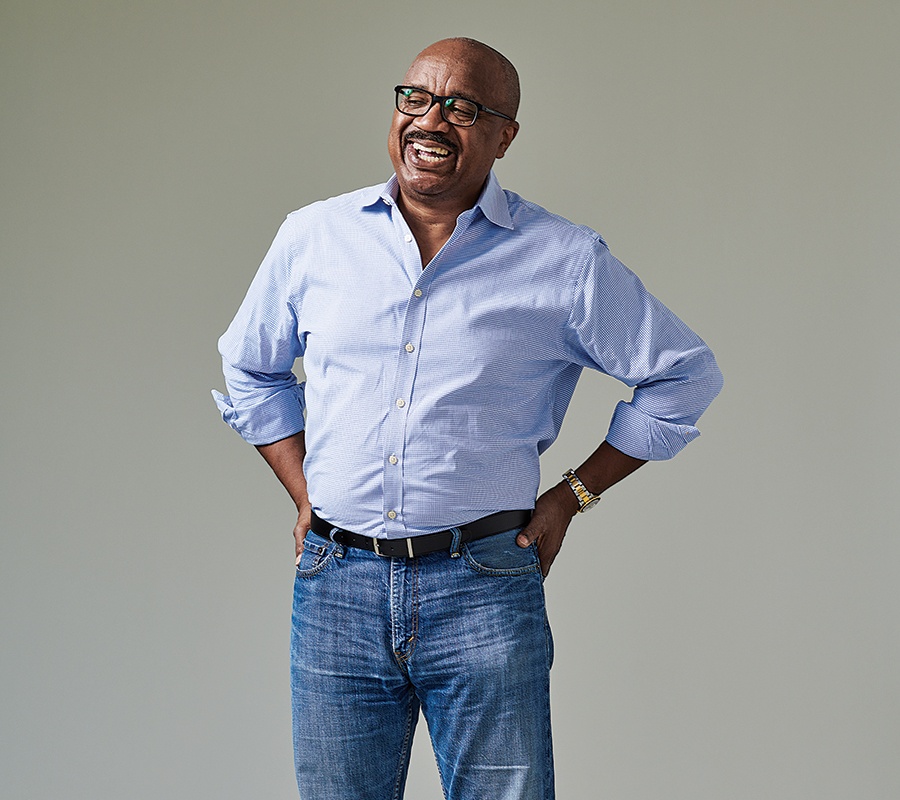

Leonard Lee

Founder, Masking the Community

When COVID-19 hit Boston like a Mack truck, Leonard Lee was sure of one thing: The disease would disproportionately devastate communities of color. A member of the Boston Parks and Recreation Commission who grew up and lives in Dorchester, he’d dedicated much of his career to public health, both in Massachusetts, where he ran the Division of Violence and Injury Prevention for a decade, and in Connecticut, where he served as the deputy commissioner for the state’s public health department. Time and again he’d observed higher rates of preexisting conditions in Black and Brown people, and believed these groups would be far more susceptible to dying from the novel coronavirus. As he watched the disease spread like wildfire throughout Boston, Lee felt compelled to act. Suddenly, a light bulb flipped on inside his head: Given his training in disease prevention and his desire to help his community, he thought, Why don’t I get masks and give them out for free?

It was early April when the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced new guidelines recommending the general public don non-medical masks. At the time, securing a commercially made mask was akin to finding a needle in a haystack. Lee knew the need was especially dire for Boston’s most underserved populations, predominantly Black and Latinx essential workers who are over-represented in service jobs that cannot be done from home. He was also concerned because nearly all of the available masks came with a price tag. “People were saying, ‘I can’t find masks’ or ‘I can’t find money for masks,’” Lee says. “Why should you have to pay to breathe? I don’t want anyone to have to decide, ‘Do I buy a mask, or do I buy food?’ That shouldn’t even be a conversation.”

So Lee started a Facebook fund-raising page asking residents to forgo one morning cup of coffee and instead donate five bucks to the cause. He set a goal of $20,000 (enough to give out about 18,000 masks), and donations—primarily in the amounts of $5 or $10—started rolling in.

With the contributions in hand, Lee was ready to get started. There was only one obstacle: actually procuring masks. Leveraging personal connections from his years in the public health sector, he worked the phones and contacted people he knew in the medical supply business, which eventually led him to securing his first 5,000 face coverings for roughly 70 cents each.

When it came time to distribute them, Lee enlisted help from college friends and former colleagues. The first place they visited was the Elizabeth Stone House, a shelter in Roxbury for domestic violence survivors. “You should have seen the faces on the women I was giving masks to,” he says. “It was amazing.” Lee got a similar reception at the Martin Luther King Towers Apartments in Roxbury, where the group went next. “They were clapping for me,” he says.

In no time, Lee and his team were making the rounds, bringing masks to senior centers, the MBTA Police, and the Suffolk County Sherriff’s Department, which needed about 10,000 masks for both guards and inmates. On some days, Lee’s group spread throughout high-traffic areas around Roxbury and Dorchester, including Hyde Square, Egleston Square, Nubian Square, Fields Corner, and Uphams Corner, handing out masks to passersby. “People would stop their cars and line up to the point where it almost started to become unsafe,” Lee says.

As word spread, Lee says, of a “crazy guy running around trying to mask the community,” more people reached out to help, and the donation sizes began to increase—including a $1,500 check from the CDC of Boston. Then Lee received a surprising call from Debora White, a former classmate from Lexington High School, where he studied as a METCO student in the 1970s. She belonged to a group of women from Wellesley, Needham, and Lexington who had formed a mask-making coalition dubbed Sewing COVID-19 and wanted to offer their services. With an enthusiastic “yes” from Lee, the group began churning out 400 handmade fabric masks a week, which Lee then gave to local service workers.

So far, Lee has raised more than $20,000 and handed out more than 30,000 masks, far exceeding his initial goals. Still, he’s not even close to finished. Residents of Worcester, Lowell, and Springfield have all reached out to Lee, asking him to help them start similar efforts in their cities. Lee is also hoping to establish additional Boston sites, such as the one he set up at Grace Church of All Nations, where walk-ins from the community can receive masks on an ongoing basis. More than anything, though, Lee says the most rewarding part has been seeing how many Bostonians have come together to help the cause. “It’s really just about being human,” he says. —Rachel Kashdan

Portrait by Karin Dailey

Jerome Crowley

Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital

Jerome Crowley is accustomed to having heart-wrenching conversations. As an anesthesiologist and critical care physician at Mass General, he spends more than half of his time in the ICU, tending to very sick patients and talking to their families. When he’s not there, he’s in the operating room, administering anesthesia to those about to undergo heart surgery or receive liver transplants. But even constantly caring for people in dire condition couldn’t have prepared him for what he experienced this spring.

When the novel coronavirus began circulating in Massachusetts, he says, he and his colleagues were afraid. Not so much for themselves, but for their patients. “We were asking ourselves, ‘How many cases are there going to be? And how many are going to come in today?’” Not knowing was the most unsettling part. He had been on calls with physicians in China and Italy, trying to learn from their experiences and gauge what Boston could expect, but there was no saying for sure.

Regardless, Crowley knew that no matter how many critically ill people came through the door, he had the tools to help them. Mass General is a Center of Excellence for ECMO, short for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, a form of life support that takes over for the lungs and the heart or just the lungs, depending on the patient’s needs, by diverting blood out of the arteries, oxygenating it, and then pumping it back into the body. “ECMO is kind of a Hail Mary,” says Crowley—one that he and his team believed could help the sickest coronavirus patients live to see another day.

The first time he put someone with COVID-19 on ECMO, it was already late in the day, and he didn’t know how many more cases he’d have that night. Since then, Crowley has essentially been on call 24/7, waiting for his phone to ring with the news that he needs to slip on his shoes and rush back to MGH. “I live 10 minutes from the hospital, so if I’m not there, I can get there very quickly,” he explains. It’s a good thing he’s so close: During the worst days of the surge this spring, Crowley says he had as many as 10 patients on ECMO at a time; typically, the number is about half that.

It was a daunting task made even more difficult by the precautions required in this extraordinary time. Usually, Crowley says, there’s a full house when a person needs ECMO: There are several nurses in the room taking care of the patient and managing their vital signs, a scrub nurse in charge of the supplies, and an assisting circulating nurse. There are also at least two respiratory therapists handling the ventilator and another two to three physicians to insert tiny tubes into the veins, which drain the blood and return it full of oxygen. And “the door is open,” he says, so intensivists and techs can come in to help as needed. But limiting the risk of exposure to the virus has meant paring that force way, way down to a skeleton crew of only three people.

The aftercare has been no less challenging. In the four to five days after a procedure—or several weeks for those in need of lung and heart support—Crowley spends the majority of his time in the ICU, getting to the hospital shortly before 6 a.m. to talk with the overnight intensivist, check on his patients, and assist with the insertion of tubes, or cannulas, into their veins. Even so, the toughest part of the past few months, he shares, has been the painful conversations during which he has to tell a family that ECMO is not a viable option for their loved one. “Everyone likes being a hero,” he says, “and it’s really tough to say no to someone, even when you know you can’t help them. You wish you could.”

Still, in many cases, the last-resort measure has saved lives. You may have heard about Hingham attorney Jim Bello, whom Crowley helped put on ECMO, and who, after nearly a month of uncertain recovery at MGH, pulled through. Those are the cases that motivate him, Crowley says: “People go into medicine to help people, and you go into the ICU because you want to take care of the sickest people.”

For all of his life-saving work, though, this is the part that Crowley emphasizes most: It’s a team. At every level, healthcare workers have volunteered their time to help care for patients with coronavirus, even before they fully understood how to mitigate the risks of infection for themselves. “People have certainly shown that they’re willing to work and take care of people,” he says. That’s why he believes that if a second wave comes to Boston, we’ll be in good hands. —Sofia Rivera

Portrait by Karin Dailey

Declan Houton

Band leader, Devri

Growing up in County Donegal, Ireland, Declan Houton gained an appreciation for the tradition of the Irish pub early on. For him, it was “the center of the community,” a place where people of all ages could gather to share stories, raise a pint, and enjoy good music. It’s a principle the construction foreman brought to Boston when he moved here 20 years ago and started the band Devri, taking the stage at crowded bars and weddings across the area. For all of his gigs, though, Houton’s most important were always the annual fundraisers for the charity Lucy’s Love Bus, which seeks to improve the quality of life for kids going through treatments for cancer and other life-threatening illnesses. “I made a promise to myself that I’d raise at least $10,000 each year for them,” he says.

When the pandemic shut down live music performances and canceled this year’s fundraiser booze cruise for the charity, then, it hit Houton hard. So the musician did the only thing that made sense to him: He re-created the experience of an Irish pub in his basement so he could still raise money for the group. What does an Irish pub occupied by one man in his basement look like? In Houton’s case, it was an iPhone propped up against some books while he played songs for a couple of hours and drank whiskey on Facebook Live. He told stories, encouraged his listeners to donate blood and platelets to Boston Children’s Hospital, chatted with the people he could see commenting on the video, and sang happy birthday to longtime commenters, all while they donated via Venmo.

The community built around the livestreams was so strong, in fact, that Houton says he often saw around 5,000 views per video. He ended up doing the concerts for 15 straight Sundays, which meant the occasional technical hiccup—“I think one Sunday I started off with the camera going the wrong way,” he admits—but a strong base of support for the charity: At press time, he’d raised more than $32,000, far surpassing his original goal.

The whole project also gave him a connection to music lovers in a difficult time. “There were so many nice, quirky things that came out of it,” he says. Taking inspiration from the Tom Hanks film Cast Away, he added a tiny in-person audience to his concerts—a Patriots football he named Wilson, which fans then outfitted with a series of hats. They also took note of his whiskey consumption, gifting him some 30 bottles of the spirit. He concedes that he wasn’t exactly a whiskey connoisseur before all of this, but says the beverage at least provides a timely conversation starter: The Irish term for whiskey, uisce beatha, means “water of life.”—Lisa Weidenfeld

Sheila Kennedy and J. Frano Violich

Kennedy & Violich Architecture

It all started with a few bags of flour for a lockdown baking project. On his way to pick up ingredients at a small Cambridge supply store in April, local architect J. Frano Violich noticed something that stopped him in his tracks: a single chair, plopped in the middle of the sidewalk outside the shop, holding customers’ orders. It got the job done, but just barely, and didn’t feel particularly welcoming. There has to be a better way, Violich thought.

Luckily, Violich, a principal at the firm Kennedy & Violich Architecture (KVA), had the resources to build a better mousetrap. With projects at a standstill, staffers had already been brainstorming ways to get their hands dirty again. So over a Zoom call shortly after that fateful shopping trip, Violich, his fellow principal Sheila Kennedy, and their team hashed out their next move: a modern, colorful “Curbside Table” for this era of socially distanced transactions.

The idea was to make the awkward ballet of selling merchandise while keeping 6 feet apart more appealing for customers—not to mention easier for business owners. The table would be sturdy, portable, and eye-catching; easy to assemble and clean; and sustainably built. “Design plays a role in going beyond just the bare minimum, survival mode,” Violich says. Most important: The firm would give out as many tables as possible for free to support local small businesses during this challenging time.

With its new mission clear, the team sprung into action. Designers who’d earlier been tasked with making plans for museums and greenhouses using high-tech 3D-modeling software began crafting prototypes of collapsible knee-high furniture, then returned to KVA’s workshop to piece the product together using the firm’s laser-cutting machinery. By late May, the initial batch was ready to go. The first tables went to KVA’s neighbors, including Haley House Bakery Café and M & M BBQ; now they can be found at shops and restaurants across the city, each a reminder to business owners that they aren’t navigating these uncharted waters alone. “Many architects right now are focused on how to throw up partitions, put glass barriers around desks—how to separate everybody,” Kennedy explains. “We wanted to try to find something that would actually help bring people together.” —Spencer Buell

Portrait by Karin Dailey

Ieasha James

Event designer, Endless Flair Events

If there’s anything event professionals know, it’s that nothing ever goes exactly according to plan. So when Ieasha James learned that all of her spring soirees would have to be postponed due to COVID-19, she didn’t despair—she just did what she’d watched her mother do growing up as part of a tightknit foster family in Cambridge. She asked, How can I help?

For someone used to dealing with the complex logistics of event design, the answer was a lot. The Dorchester resident started by delivering groceries to neighbors and a care package to a local nurse working on the frontlines. Then she spotted a post on state Representative Liz Miranda’s Facebook page about a family of 11 that needed assistance. In addition to bringing them food and cleaning supplies, James asked one of her vendors to create Easter baskets for all nine kids, and prayed by phone with the mom, who suffers from anxiety. And when she learned one of the woman’s daughters would be turning 12, she did the obvious—she designed a lockdown-friendly celebration for her, complete with a birthday-in-a-box overflowing with streamers, balloons, plates, and favors. “I asked the mom her favorite color and grabbed everything at the store that was purple, along with an ice cream cake and cupcakes,” she says. Her gift to the birthday girl? Fifteen new outfits.

Determined to keep spreading a little joy during a difficult time, James then reached out to a representative from the Ellen S. Jackson Apartments, a senior housing development in Roxbury, to see what she could do for the residents there. Working with chef Brian Alleyne of Simply Irresistible Cuisine, who donated his time, James organized complete dinners—from spaghetti with meat sauce and garlic bread to a soul-food-themed menu—for 40 seniors on three consecutive Sundays in May.

For James, the good deeds were just an extension of the work she does every day as the owner of Endless Flair—which has coordinated multiple events for Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley—and an active community member who supports local causes and serves as a mentor for Chica Project, a youth and leadership development nonprofit. “I do this for the same reason I do events,” she says. “The end result: joy.” —Marni Elyse Katz