The NAACP Convention That Never Came to Town

Edited by David S. Bernstein

Illustration by Comrade / Photo via Getty Images

Keynote Address

Deval Patrick

Former Massachusetts Governor

America is a country built on aspiration, a nation reaching for the ideals expressed at its founding. Reaching, yet not grasping them in hand.

In many ways, the story of this country is a story of that reach, of trying to make life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness a reality for all Americans.

Boston and Massachusetts have long served as a microcosm for America. That is especially true when it comes to the gap between ideals and reality, especially for Black and brown residents.

We are the birthplace of public education, yet today too many students, mostly Black and brown students, are caught in a vicious achievement gap. We are a world leader in healthcare, but racial disparities in chronic illness, infant mortality, and life expectancy are as profound here as anywhere in the world. We have been the birthplace of social progress and change, from the abolitionists to the suffrage movement to the fight for marriage equality. But to be Black or brown here today can still bring harrowing, frustrating, sometimes life-threatening discrimination.

We see these disparities in data and in the everyday experiences of Black and brown citizens of Massachusetts. I, like every other Black trial lawyer I know, have been mistaken for a defendant awaiting trial and directed elsewhere when I came to sit with other attorneys near the bench. Neither the cut of my suit nor the quality of my briefcase mattered. In fact, every Black professional I know has had similar experiences, all the while working twice as hard for half the recognition.

Racism is at the root of the wealth and income gaps between Blacks and whites. It is the cause of the disparities in health outcomes. It is why we still see persistent housing segregation, food deserts, and criminal-sentencing discrepancies. Yet we cannot ignore too that the ways we have changed our values in business have exacerbated many of the inequalities we see.

While I am a capitalist and have spent much of my career in the private sector, it’s clear that American capitalism is now needlessly harsh and has contributed to our feelings of constraint. The profit model for many companies is based not on innovation, but on wage suppression and job cuts. Meanwhile, residents are no longer protected by much of a safety net. Instead, their economic stability is dependent on that job—lose it, and there goes a family’s healthcare, housing, food, childcare, and retirement plan.

Considered commonplace for Black Americans for generations, these harsh realities— economic uncertainty, social marginalization, barriers to moving up—are now shared by most other Americans, and not just here in Massachusetts, but everywhere across the country.

And yet, I am hopeful. In the midst of a pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands, a teetering economy that casts a shadow over everyone’s future, and a racial reckoning long in coming, Bostonians, like Americans everywhere, are overwhelmingly responding with empathy and compassion. We are asking hard questions of ourselves and being open to hard answers.

I see young Black people taking to the streets to demand justice. I see them joined by people of every background, age, and station. They have put their collective foot down to demand for Black people the same rights that every American is taught to believe is our birthright: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

I am hopeful because I see our nation is still marching toward justice. We need young activists to continue to push us and we need leaders in government and in business to listen.

It is time for bold action to reinvent our nation, and I see in Massachusetts today a new generation of leaders, activists, elected officials, and everyday citizens who are ready to help America boldly reinvent herself. They understand that while the gaps between our ideals and our reality have grown, the tools to close them lie within their reach. Right here, right now. In our commonwealth, in our lifetime.

Photo by David Becker/Getty Images

Moments in History

A timeline of the NAACP in Boston, where it was kinda founded.

1909

In response to news of lynchings and anti-Black riots, a group of racial justice activists, including members of William Lloyd Garrison’s family, William Monroe Trotter, and former Massachusetts Attorney General Albert Pillsbury, created the Boston Committee to Advance the Cause of the Negro. It, and a similar group in New York, were the predecessors of the NAACP.

1910

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was officially formed, naming Boston lawyer Moorfield Storey as its first president. Storey, a white Roxbury-born Harvard Law graduate, led the group’s strategy of using the 14th and 15th Amendments to challenge discriminatory laws and practices.

1911

During an NAACP conference at Boston’s Park Street Church, the Boston Committee to Advance the Cause of the Negro became the very first branch of the NAACP.

1913

In its first major victory, Boston’s newly minted NAACP chapter forced the YMCA to stop excluding Black boys from using its swimming pool.

1941

As a result of the Boston NAACP’s investigation of colleges, Boston University announced that Black women could live in its previously all-white dormitories.

1972

The Boston NAACP filed a lawsuit against the Boston School Committee that resulted two years later in Judge Arthur Garrity’s desegregation order.

1975

The day after Judge Garrity put South Boston High School into receivership for failing to follow his desegregation orders, someone threw a Molotov cocktail into the Boston NAACP’s branch office at the corner of Massachusetts and Columbus avenues.

1982

The 73rd NAACP National Convention convened at the Park Plaza Hotel—the last time Boston has hosted the event. Although the city was eager to present itself as past the tensions of the busing era, the convention took place in the shadow of news that a house in a white Dorchester neighborhood had been firebombed after three Black families moved in.

1988

In a nationally watched case, the Boston NAACP won a class-action lawsuit forcing the Boston Housing Authority to desegregate its housing projects and compensate Black families affected.

2020

The NAACP selected Boston to host its national convention, with thousands expected to attend, but was later forced to cancel due to COVID-19 concerns.

Luncheon

Roadmap to a Better City

Five Black leaders tell their truth about race in Boston—and offer thoughts on how to begin tackling the city’s biggest hurdles to equality.

Photo by Emmanuel Boakye-Appiah

Collaborate, Collaborate, Collaborate

Makeeba McCreary

Chief of learning and community engagement, Museum of Fine Arts

The thing that has improved since I grew up in Boston is the ability to cross lines through different cultural sectors and communities. My son can go into neighborhoods that it didn’t even cross my mind I could explore. He has the freedom to operate without as many definitions of what he can and cannot do; who he can and cannot be.

Other aspects have not improved. After the murder of George Floyd, communities mobilized almost overnight—where were all of you a month ago? Where were you last year? What is it about today that has all of you come out with signs and decide that you’re going to protest the inequities of our world and our city, when Black folks have been suffering and challenged in trying to participate with equity and grace?

We have to do better. There has to be a world in which our leaders work together to create some change. We owe it to this generation of young people, and we owe it to ourselves. This is an incredibly beautiful city, with diversity and great opportunities. The key is that the work up until now has been fairly siloed. The corporate sector has worked among itself; the philanthropic sector has worked among itself; individual leaders have worked in a siloed way. If we could embrace the different gifts that the folks in this city bring to bear, then we can actually do something that’s different. You know, until we had to figure out how to respond to this pandemic, I didn’t talk to my colleagues at the Gardner and the ICA; now I’m on phone calls with them once a week. So I hate to say that there’s a blessing in something as catastrophic as COVID-19, but it’s given us an impetus to work together to move forward.

We have to become less patient. I do not accept that we have two years, or that we have two months. It’s right now. It’s not going to be easy, but I don’t think that it’s as hard as we’ve made it.

Photo by Emmanuel Boakye-Appiah

By the People, for the People

Conan Harris

Founder and CEO, CJ Strategies

As a person who has dedicated my life to better the conditions for Black citizens in the city, state, and country, it is great to see young people from all different backgrounds at the forefront, connected and united. They are going to be the new lawyers, the new judges, the new police officers, the new mayors.

People now see the connective tissue between activism, marching, and policy. You have lawmakers like my wife, Ayanna Pressley, who is a great mixture of an activist and a policymaker. Other policymakers, you have to nudge a little bit. The best policies are driven by the people that they’re made for. That’s when you see real change.

You’re already seeing it a little bit. Months ago you would have never seen a bill pass here to change qualified immunity, to allow police to be held responsible for their actions. But we cannot get one victory and rest on our laurels. We have to keep pushing to get folks to understand that it will make your business, your company, your government better and more successful when it’s reflective of the citizenship that you represent.

Photo by Emmanuel Boakye-Appiah

Equal Access To Opportunity

Nia Grace

Owner, Darryl’s Corner Bar & Kitchen

The city talks about the diversity here, and why it’s such an ideal place to host conferences and events. Then the reality is that if I want to win a contract to provide food for an event at the convention center, the answer is no. The same for small Black-owned companies who do audio-visual work, or floral work; if you’re not on their list of qualified suppliers, you’re not going to be a vendor. I applaud the NAACP locally, for making sure African-Americans could also be a part of that celebration, and that revenue. You can’t want our dollars but not the businesses and the people that they represent. This is really about equity and access. And not just this one time, but figuring out how this can be the norm.

It needs to be more intentional, in terms of reaching out to our businesses and actually reducing the barrier to entry. Our businesses can’t participate in Dine Out Boston, for instance, if they’re not a member of the Greater Boston Convention & Visitors Bureau. And if the cost is prohibitive, they just don’t get a chance to participate in that opportunity. We’re trying to come up with solutions. That’s why I and several other restaurant owners created the Boston Black Hospitality Coalition this year, because we have to get creative in taking care of ourselves and putting ourselves out there to be discovered.

Photo by Emmanuel Boakye-Appiah

Challenge Everything

Emmett Price III

Founding pastor, Community of Love Christian Fellowship, Allston

In his letter from the Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr. suggested that he was more concerned about the white moderate, who was more devoted to order than to justice, than with the White Citizens Council. And that’s what I see in Boston. Boston has a great narrative, when it’s self-told: that Boston is more progressive and forward-thinking than other cities. But I have lived in Los Angeles, California; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Bloomington, Indiana; St. Louis, Missouri; and Alexandria, Virginia. My lived experience, as a Black man who has been here since 2001, is that Boston is just as racist, if not more racist, than other cities I have lived in.

I was still in Los Angeles during the Rodney King riots, and I remember the angst, and the anger that I had as a young person. I think that for our young people today, it comes from seeing capital punishment of Black people on their phones, without due process, time and time again. Enough is enough.

The NAACP, whose first chartered branch was here in Boston in 1911, came out of the Niagara movement for self-determination and to reinvest in their own communities. The challenge of the millennial generation and Generation Z to the NAACP is, What have you all been doing for 110 years, for us to still be here? Do we still need the NAACP, or do we need a new mechanism, a new aspiration? Because we have made progress, but Black people continue to have to put their bodies on the line, and invite others to put their bodies on the line, so that we won’t be killed. And that statement should not be said in 2020.

Photo by Emmanuel Boakye-Appiah

A Shift in Power

Sheena Collier

Founder and CEO, the Collier Connection

I’ve been here 16 years and a lot of people ask me why I’m still in Boston. Boston’s brand is exclusivity: Who do you know, who can vouch for you, are you in? That is a challenge for anyone, but it adds another layer if you’re a person of color. What’s keeping me here doing this work is that Boston has a lot of potential. If we all continue to push in the same direction, we can shift things here. It’s really about pushing past the current structures that are in the way. Those structures are the people, foundations, and corporations in power who might support a new initiative or give millions of dollars toward an effort, but no one is really going to give up their power. For this to really change, they need to say, “Maybe I need to be replaced, maybe I need to build a successor who doesn’t look like me, or wouldn’t have the access that I’ve had.”

But I also think that Black people have to build and create our own spaces, and own our own alternative economic structures. I’m calling them alternative, but it’s just different than the mainstream. Having ways that we instill history and education into our own children. So that while we are working in places where we are not the majority, and we may not be seen, we’re also doing things for ourselves in our own communities, to fortify ourselves to be seen in other spaces.

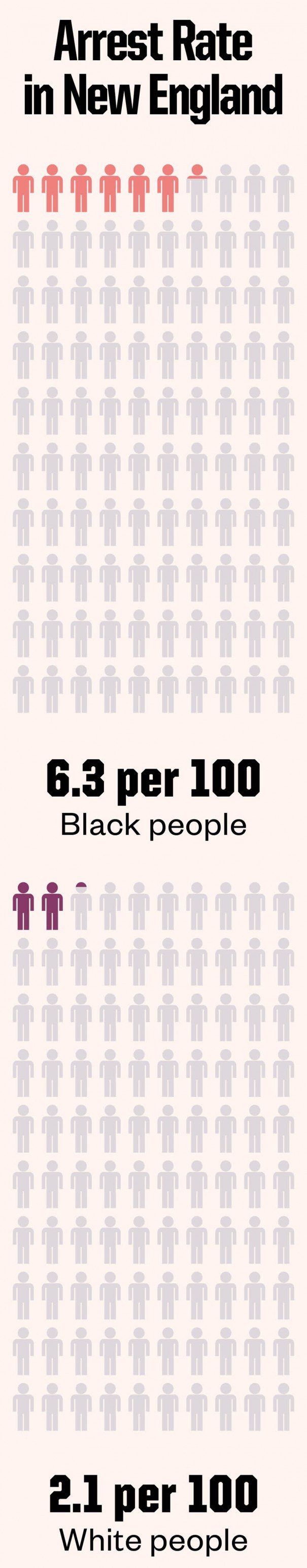

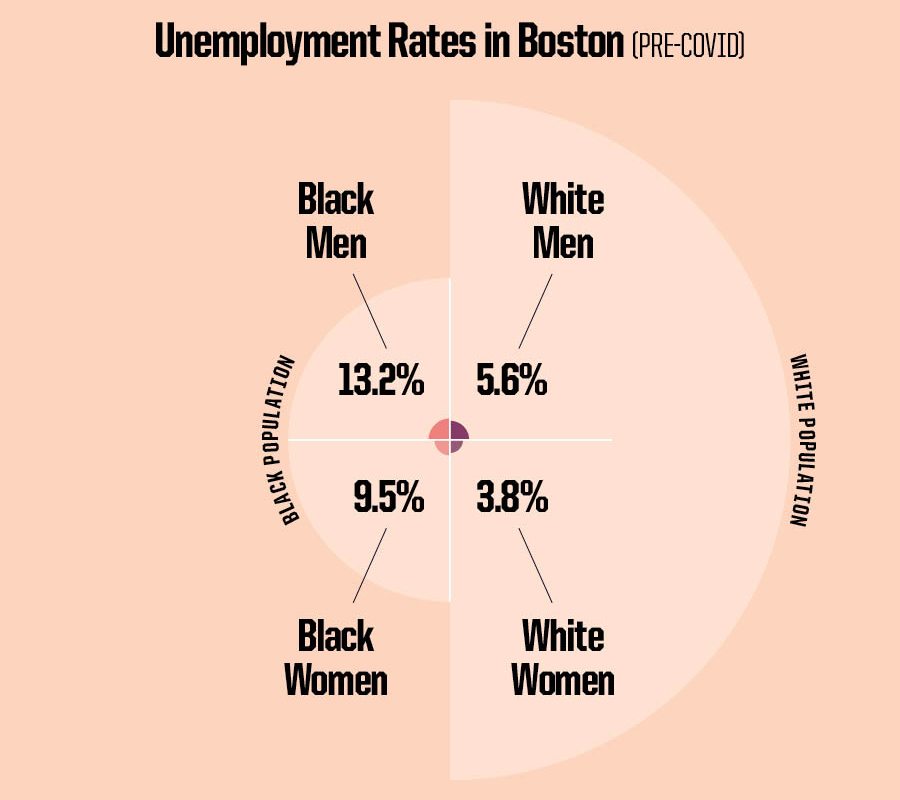

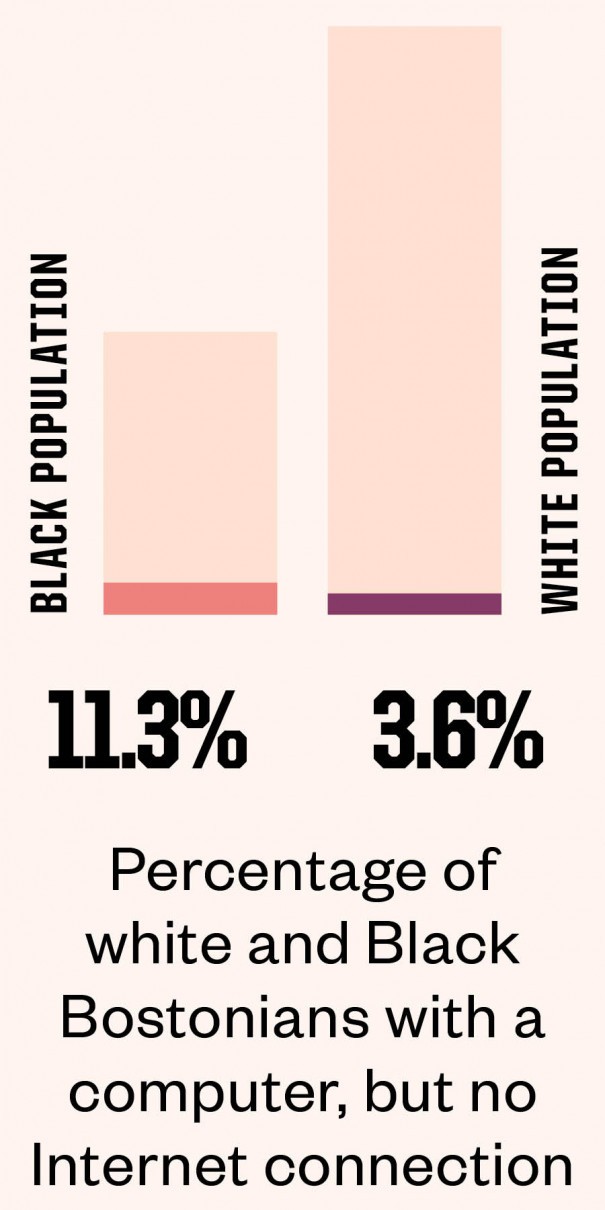

Powerpoint Presentation

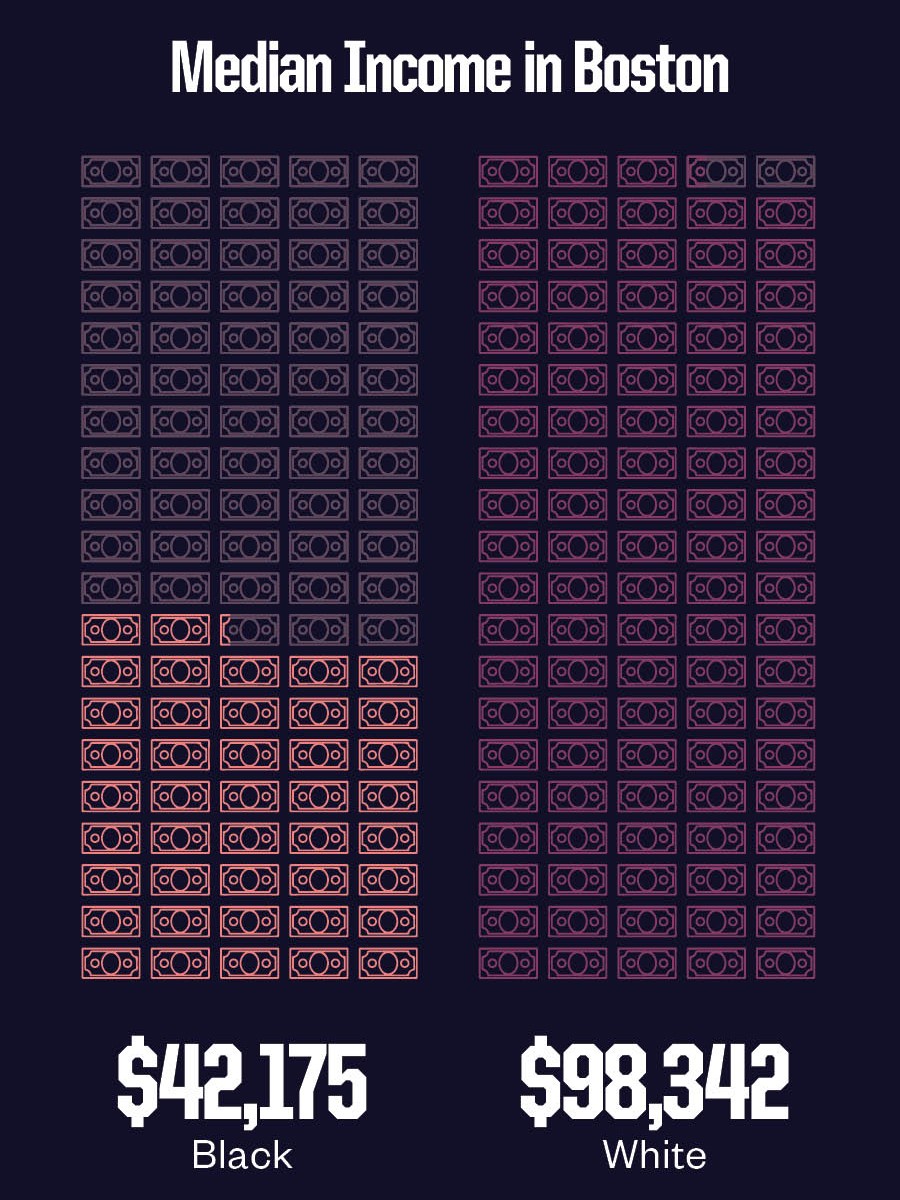

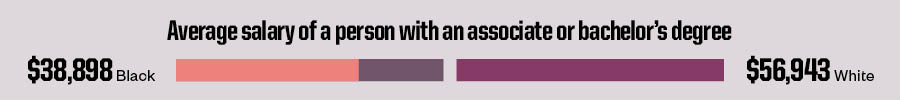

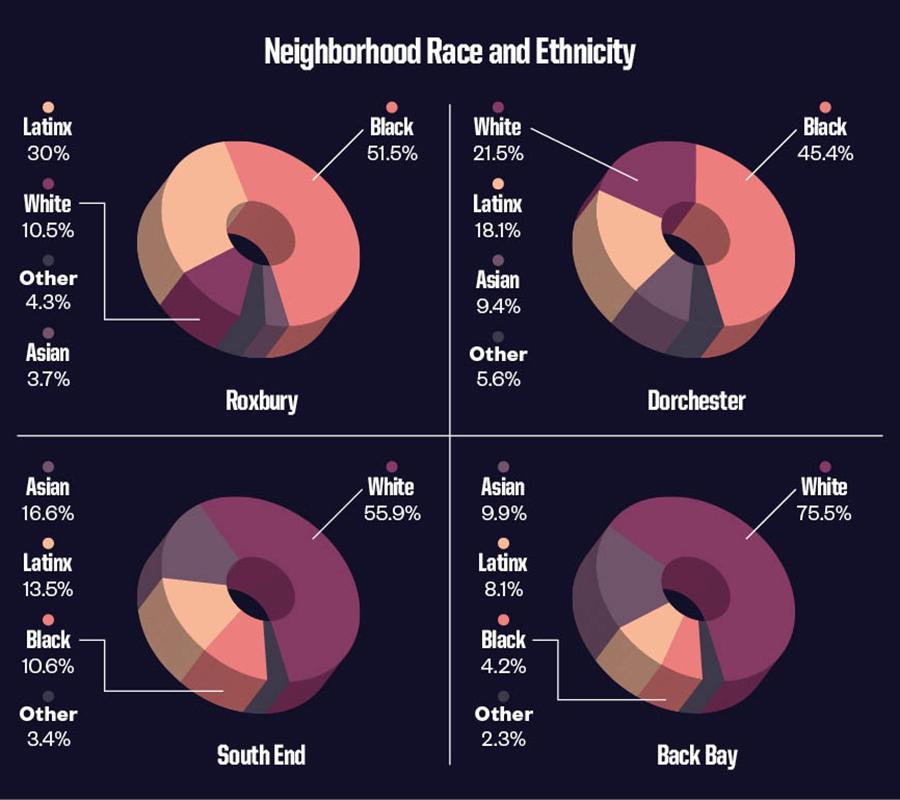

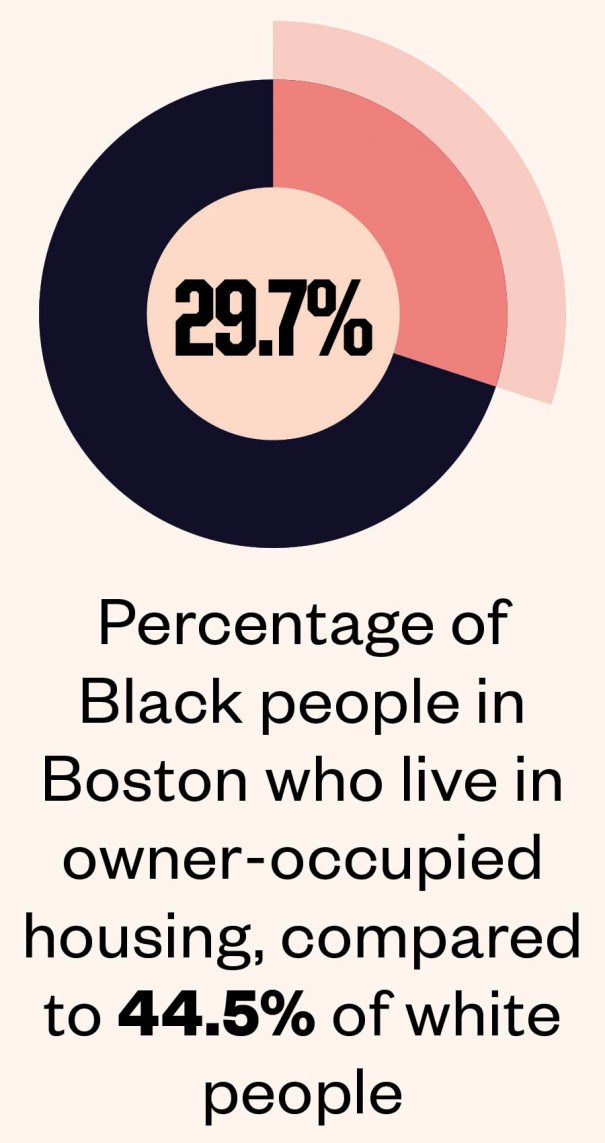

Race in Boston: By the Numbers

From healthcare to homeownership, we still have a long way to go toward making the city a more equitable place.

Source: NAACP Boston Branch; Boston Planning & Development Agency; American Community Survey

Breakout Session

How City Hall Can Fix Itself

In a time of self-reflection, here are three ways Boston’s government can right its own wrongs.

Photo by Phil Cardamone/Getty Images

Show Black contractors the money

Marty Walsh’s administration recently boasted that nearly 5 percent of the city’s $600 million-plus in contracts is going to companies owned by people of color—an increase, but still far behind other large cities, and not nearly enough to make a serious dent in Boston’s wealth gap. The Black Economic Council of Massachusetts (BECMA) is calling for the city and state to commit to awarding at least 10 percent of their contract dollars to Black- and Indigenous-owned businesses.

Re-diversify the payroll

In 1974, a federal court forced Boston’s police and fire departments to begin hiring one POC candidate for every white hire. Those decrees were lifted 30 years later, as judges ruled the departments were successfully integrated. But today, as the original consent-decree hires reach retirement age, the failure to maintain that integration is being exposed. The city needs to find new solutions and show real results, or risk finding itself back in court. “If we discover that the city is unwilling to diversify its workforce, then we need a new consent decree,” says City Councilor Lydia Edwards.

Start a housing war with the state

Gentrification and other factors have priced far too many Black residents out of Boston, which means, among other things, that they are ineligible for many city jobs. Some current proposals to increase housing affordability, including updating city zoning laws, require the blessing of the state legislature, which continues to turn a blind eye. But Boston could do more on its own, says Lisa Owens, executive director of City Life/Vida Urbana, by increasing support for tenant organizations and acquiring more affordable housing. “We need structural reform to make it easier for people who work in the city to live in the city,” Owens says.

Workshop

Broken Promises?

The NAACP convention was supposed to foster fundamental change throughout Boston’s business community. What happens now?

When the NAACP announced it was coming to town late last year, local leaders were looking forward to more than just the meetings and speeches scheduled to take place inside the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. They were excited about the money that promised to flow into the local economy, not to mention the opportunity to demonstrate that Boston is a welcoming place for Black visitors. Plans before, during, and after the convention included several events at the Boston Public Library; a red-carpet Basquiat Ball at the Museum of Fine Arts; a Taste of Black Boston festival on City Hall Plaza; a Duck Boat Black history tour; and gatherings on the Lawn on D.

Most important, many were excited about how the NAACP convention might have prompted the city’s corporate world to commit to real change. “The opportunity presented by the convention,” says Pratt Wiley, president and CEO of the Partnership, which promotes the success of multicultural professionals in Boston-area business, “was to focus the business community on race and equity, and to mobilize the business community around fairly specific calls to action.” And mobilized they were: When Mayor Marty Walsh began dialing for dollars to finalize convention plans, local bigwigs were eager to pony up, quickly offering all of the money Walsh was looking for. The Massachusetts Competitive Partnership (MACP), for example, which includes the top executives of Fidelity, Liberty Mutual, MassMutual, Wayfair, and other area titans, pledged $3 million.

It wasn’t just big checks, says Jay Ash, MACP’s president and CEO. There was talk, he says, of sponsoring and hosting events, giving office space over to convention delegates, and committing to specific goals—increasing diversity of executives and boards of directors, for example, or providing access to capital for Black and Latinx small businesses and entrepreneurs. “Without a convening event, it never seems to happen,” Ash says. “With the [NAACP] announcement, it was a eureka moment: This is where we can have everybody in the room.”

Where those good intentions go now, in the absence of the convention, remains a very open question. For a while, the momentum seemed to remain, particularly after the mass protests following the death of George Floyd. In July, for instance, more than 30 Massachusetts business associations—including Associated Industries of Massachusetts, the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, and the Retailers Association of Massachusetts—released a statement acknowledging “systemic oppression and racism” and committed to “hold ourselves accountable.”

By the time the NAACP’s virtual convention began in early August, though, hopes for real change had started to fade, according to Segun Idowu, executive director of the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts (BECMA). Idowu had expressed optimism a month earlier, as business leaders seemed to embrace concrete steps outlined by BECMA in a June document. But as protests petered out, and the expected spotlight of the convention disappeared, Idowu found that same group of people has suddenly become “content with words like ‘We’re going to encourage…’ or ‘We’re going to work with,’” he says. “I have yet to see any real commitment to addressing systemic racism.”

If that’s so—if the change some hoped the NAACP convention would bring has in fact been lost—it might be a long time before Boston’s Black community feels optimistic again.