Let It Be

Photos by Eric Roth / Styling by Stephanie Rossi

The 19th-century North Shore home was underused and out of date. A dearth of bathrooms, both upstairs and down, made it hard for family and friends to enjoy their stay. The kitchen, designed for servants, was no fun to use. To make matters worse, the house was also drafty and uninsulated. The sixtysomething brother and sister who’d cared for the 1.5-acre seaside property for decades wondered if it might be time to sell.

The pair turned to Timothy Thurman, founder of the Rockport-based Treehouse Design, for advice. If sold, Thurman told them, the 8,000-square-foot home would likely be razed and the property subdivided—it just wouldn’t be worth a developer’s money and time to try to salvage the quirky abode. The thought of the house being knocked down weighed heavily on the family. The shingle-style “cottage” had been built by their grandfather and great-uncle in 1898 as a double house for their respective families. Not only was it steeped in history, but every nook and cranny reminded the owners of their childhood summers spent hiding in the eaves, spying on the adults from the upper porches, or playing charades in the great room. No, they couldn’t stand to see the house knocked down. But now that their children were having children, what could they do to revive the summer-cottage tradition?

The obvious answer was to give the home a major overhaul, inside and out. So they hired Thurman, along with interior designer Maureen Neville, to reclad it with red cedar shingles, put on a new asphalt roof, and install new windows. As the cosmetic renovation proceeded, they considered adding insulation. Thurman, a passionate and careful craftsman, made the case for keeping it a traditional summer home. Winterizing the house would require filling in the interior bays with insulation and sheathing the place with drywall, “taking away the house’s quaintness,” Thurman says. “People back in those days had it right,” he continues. “They built with just wood—no plaster—and enough air moved through the houses that they didn’t end up rotting. Whenever the water got in, which it often did, it eventually found its way out.”

Though insulating had obvious advantages, as an unheated building, the cottage was easy to maintain. The family could close up the porches, strip the beds, drain the pipes, and leave it alone all winter. In the end, they decided to keep it that way, and if their children or grandchildren wanted to add insulation later on, well, at least they were starting on solid ground.

Thurman added two new gas stoves and removed the site-built kitchen cabinets, replacing them with new custom cabinets made in his shop. He created nicely sized guest rooms by combining the original maid’s quarters and one of the sleeping porches. Down in the basement, he converted an unfinished boat-storage area into a rec room with a TV.

But as much as this story is about what Thurman and Neville did do to the house, it’s also about what they didn’t do. The great room, with its inglenook seating and dark, southern longleaf pine floors, is just as it ever was. Upstairs, 12 bedrooms of various sizes spill into one another, creating a cheerful, slumber-party-like atmosphere. Even the large sleeping porch remains, with its massive green-and-white-striped shades. There children lie on blankets and tell ghost stories on hot summer nights.

“The thing about this architecture,” Thurman says, “if you drew the elevations of this house, you’d say, ‘This is really homely.’ I mean homely in the original sense—homey, comfortable. In some ways, that homeliness is comforting. Nothing matches up. On paper it’s out of proportion, but in reality you have something very much in balance. As architects, we get so enamored with our drawings, it’s hard to create a structure that’s so rambling and organic.”

Time-worn floors and simple whitewashed clapboard interiors create a carefree vibe in this seaside cottage.

The deep first-floor porch, second-floor sleeping porch, and three-season porch offer plenty of spots for reading, playing, and contemplating. The home’s foundation was built on exposed granite bedrock.

Unfussy heirlooms and family portraits serve as reminders of summers past.

Vintage family photos, knicknacks, and tiny figurines add historical texture to the cottage.

The brick hearth and Arts and Crafts–style inglenook encourage family gatherings on chilly nights.

An informal dining area adjacent to the kitchen features mistmatched chairs and a collection of blue-and-white porcelain dinnerware.

The landing between the kitchen and the living room has been the setting for countless rounds of charades.

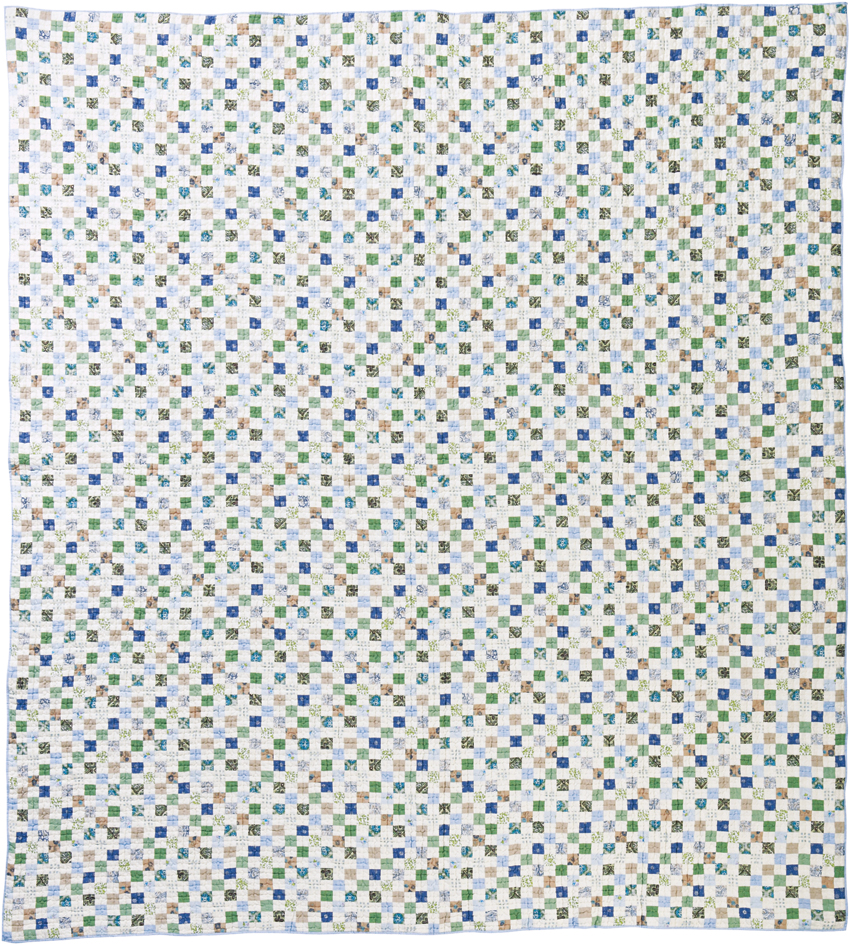

The children’s bedrooms are outfitted with quilts and antique games.

A mantel in the dining area features a vintage wedding photo.

Early-2oth-century photographs of the property and family members hang in the second dining room.

Vibrant custom-built kitchen cabinetry and a beadboard backsplash fit right into the rustic home. Get that look.

Architecture Tim Thurman, Treehouse Design, Rockport

Interiors Maureen Neville, Treehouse Design, Rockport

GET THAT LOOK

Where to find décor inspired by the kitchen this story.

“Spring Harbor Postage Stamp” quilt, $239, L. L. Bean, 6 Wayside Rd., Burlington, 888-552-9866; and other locations; llbean.com.

Vintage porcelain servingware, starting at $35 per piece, Devonia Antiques for Dining, 15 Charles St., Boston, 617-523-8313, devonia-antiques.com.

“Spin” 24-inch stool, $100, Crate & Barrel, 777 Boylston St., Boston, 617-262-8700; and other locations; crateandbarrel.com.