Iron Lady

photograph by jared leeds

Jane Thompson sits in the same Franco Albini chair that her late husband, Ben Thompson, was photographed in for Look magazine in 1962.

Throughout her extraordinary career, design maven Jane Thompson has curated shows at the MoMa, cofounded I.D. magazine, and revitalized civic spaces such as Faneuil Hall and New York’s Grand Central Station District. Her greatest achievements, however, sprung from an incredibly fertile four-decade-long collaboration with her late husband, the acclaimed architect Ben Thompson. Together through their experimental Cambridge-based retail venture, Design Research, they brought modern interior design to the U.S., importing beautiful and affordable home furnishings from Europe after World War II. Always a feminist first, Jane has long advocated for injecting the female perspective into the traditionally male-dominated design industry, challenging gender roles in the office and in life. Today, as principal of her own firm, Thompson Design Group, she explores design with an emphasis on historical preservation and the imaginative repurposing of underused spaces.

Tell us about your involvement with Faneuil Hall in 1976 and why it was important for cities everywhere.

It took us 10 years, and it was very big for Boston. It changed the quality of the center of the city. People had left the downtown quite abandoned and were in the suburbs, eating in malls—there was a complete vacuum. In order to change that, we wanted to create a market where you could buy food and eat it on the street. The idea was you could be outside in a public space and be part of the city, the way you used to have an old town square in a small town. Once it opened, it revitalized the whole downtown. It became a central gathering place where you could occupy the outdoors freely in benches, like a park. It was such a rediscovery. It completely reversed the trend. People reoccupied and business followed. It also brought access to the waterfront that everyone had been denied for years, because it had been an industrial place for shipping and trucking and all that. We woke people up to the value of waterfront land for social, recreational, and commercial uses.

I hear your husband was quite chummy with Jackie Kennedy Onassis.

Jackie O. was a nice lady, and a classmate of mine in college. She didn’t know me, but she got to know Ben, and she liked him. She shopped in his store and came around visiting him. One summer she bought eight Marimekko dresses from Design Research in Hyannis, and appeared in them on the cover of Sports Illustrated. That was the best thing to ever happen to the Fins. She was wearing her Marimekko dresses during her pregnancy with John-John. Jackie was a woman of great taste. She lived on the Cape and we lived on the Cape, and we all traveled back and forth. Every now and then Ben got an airplane ride back to Boston, and Jackie was the other passenger.

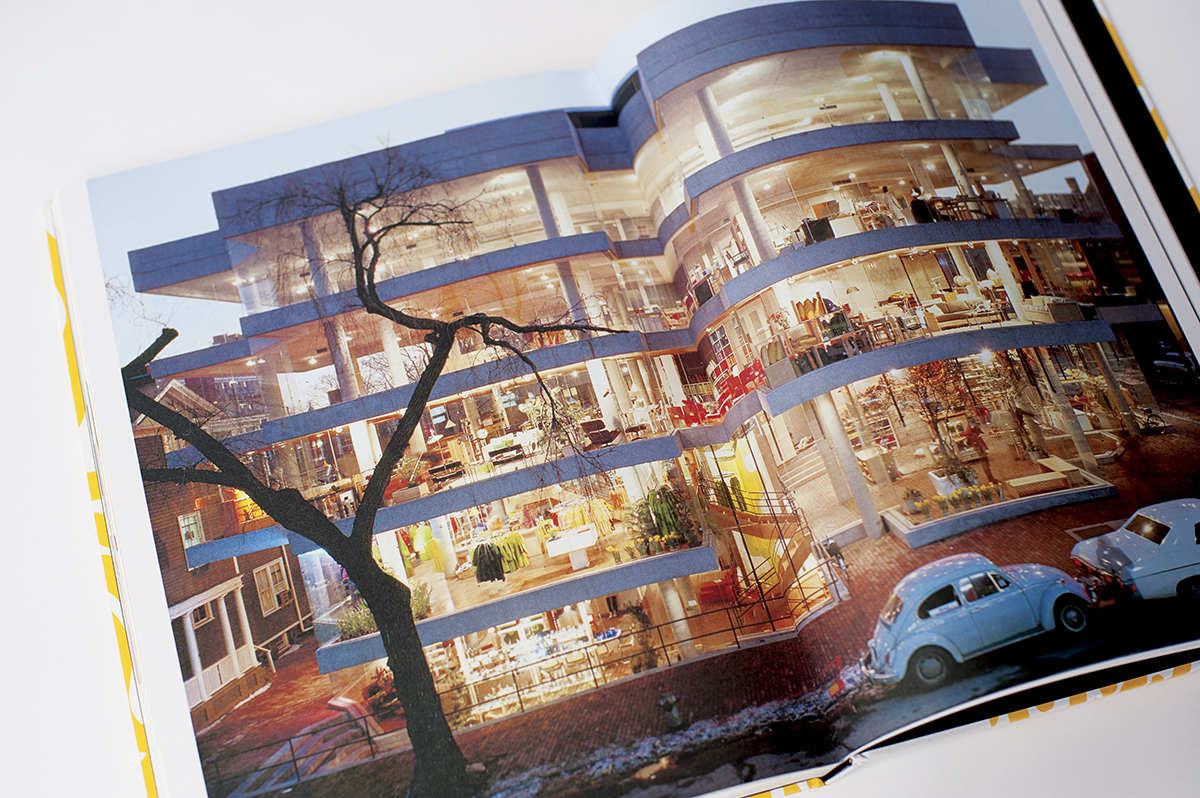

photograph by jared leeds

The Harvard Square outpost of Thompson’s retail venture, Design Research, as it stood in 1970.

And how did your long-standing relationship with Marimekko begin?

It was 1958, and the Brussels World’s Fair was a very big deal. Ben went and he saw beautiful handcrafts, ceramics, fabrics, and girls in brightly colored dresses in the Finnish pavilion. He had a student over there on a Fulbright at the time, and he said, “Find me who did the selvage of this fabric,” and it was Marimekko, although it wasn’t yet called that. So Ben invited the company’s design team to come to Cambridge and put on ›› an exhibition of their work in ’59. The girls came and the dresses came and they sold out in about 20 minutes. From then on, Ben was the distributor for Marimekko in the U.S., and he edited many of their designs. We had a very strong relationship with the company through the ’60s.

That led to your eventual knight- hood and your nickname, Sir Lady Jane, right?

Yes. In 2002 Ben was bedridden and we got a call from the president of Finland saying, “We would like to make you a knight, you and Ben both.” I said, “That’s Finland for you!” It was for our attention to their potential and their arts and design. They declared us Mr. and Mrs. Knight. The ambassador for Finland came to New York and we had a ceremony and got our medals. They don’t have all these gender hang-ups like we do. I didn’t ever ask if there was another woman in the Finnish knighthood, but I said, “I don’t want to be the wife of a knight. I want to be a knight knight.” Someone came up and said, “Sir Lady Jane. That makes you both.”

Tell us your theory about the “double win” in designing.

It came to me in 1975, when I was asked to speak at a women’s design conference at the Boston Society of Architects. At the time women were trying terribly hard to be accepted in the architecture profession by designing like Mies van der Rohe and overall trying to be more like men. I’d see a floor plan and a bed would be pushed off into a corner—you couldn’t even make it, let alone get in or out of it. I said, “You know better than this. You’re not going to live like that, why are you putting it in your plans for other people? Men aren’t thinking about the functional interaction between beds and cleaning, so you need to build this into your lives. You know something men don’t.” The ›› truth is we need men in design just as much as we need women. Because they think differently, and together they get it right. I called it the world of the double win.

How do you feel about Boston as a city now, after watching it bloom and grow for decades?

I think Boston is a great solution for living, but it has limited dimensions. As a city, its general architectural character is very strong. But there are things in Boston that are so out of character and disruptive to its harmonious way of working because they’ve been neglected for so long. The connective tissue of the T has not been perfected, especially in outskirt neighborhoods. There’s a real lack of public housing. If a developer wants to come in and build public housing, that’s allowed, but it doesn’t stir the public needs in terms of programs or a city plan. The state government isn’t thinking of a city plan, because they don’t think we should have one—it gets in the way of deals. They think everything should be driven by private enterprise, and they do a lousy job of monitoring developers. I think the progressiveness of it is sometimes very ill advised. That said, the improvements to the tunnels have been enormous—we finally have the ability to travel long distances without fighting through downtown. And the pace of the city and its casual attitude about life are very restful. You don’t have to get all dolled up to show up somewhere if you don’t want to. It’s not Fifth Avenue, thank God.

photograph by jared leeds

A tribute to Design Research hangs near the entrance to Thompson’s Fort Point design firm.