A Glimpse of the Past at the Gibson House

The interior of the Back Bay’s Gibson House reveals how Boston’s wealthiest denizens (and their servants) lived and worked during the Victorian era. / Photograph by John Woolf

Walking along Beacon Street in the Back Bay, you might not notice anything special about house number 137, located just a block from the Public Garden. But inside, this residence turned museum, where nothing has been altered since 1954, offers a rare glimpse of Boston’s golden age.

Built in 1860 by Catherine Hammond Gibson for her son, Charles Sr., the Gibson House occupies the second lot developed after Boston began filling in marshland to create the Back Bay neighborhood. Over the next 40 years, the public works project would yield 570 acres of land, on which many of Boston’s most affluent families built their homes.

This house was designed by Edward Clarke Cabot, the architect behind the Boston Athenaeum, and features the eastern and western motifs that were all the rage during the Victorian era. From the French mansard slate roof and Italianate brownstone arches around the windows to the foyer’s gilded “Japanese Leather” wallpaper (embossed paper, added in 1888 by Charles Sr.’s wife, Rosamond, a member of the prominent Crowninshield family of merchants), the Gibson House is considered an exemplar of 19th-century Boston residential design.

Photograph by Mary Prince

Unlike other townhouses of the era, the entrance is centered on the façade. On the other side of the heavy carved walnut double doors is a spacious foyer with high ceilings crowned by a multistory ventilation shaft—a Victorian innovation that served to draw warm air up to all parts of the home while providing natural light from its skylight. Beyond is the dining room, featuring a grand mahogany table. A majestic curving black walnut staircase leads to a landing, where a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s famous painting of George Washington at Dorchester Heights hangs, along with many other works in heavy gilded frames.

Designed for entertaining guests following lunch or dinner, the second floor is divided into men’s and women’s areas, including a paneled library where Charles Sr. conducted business for his cotton brokerage. Family portraits, lamps, tables, and wall-to-wall carpeting abound, just as they did during the home’s heyday. The third floor contains two bedrooms connected by a bathroom with plumbing that was last updated in 1902. The larger bedroom boasts a 15-piece bedroom set built of bird’s-eye maple.

A network of narrow hallways leads to the servant’s kitchen, where a side door opens onto one of the Back Bay’s many public alleys, through which deliveries were received. Servants would also use this route as their entryway.

Photograph by Mary Prince

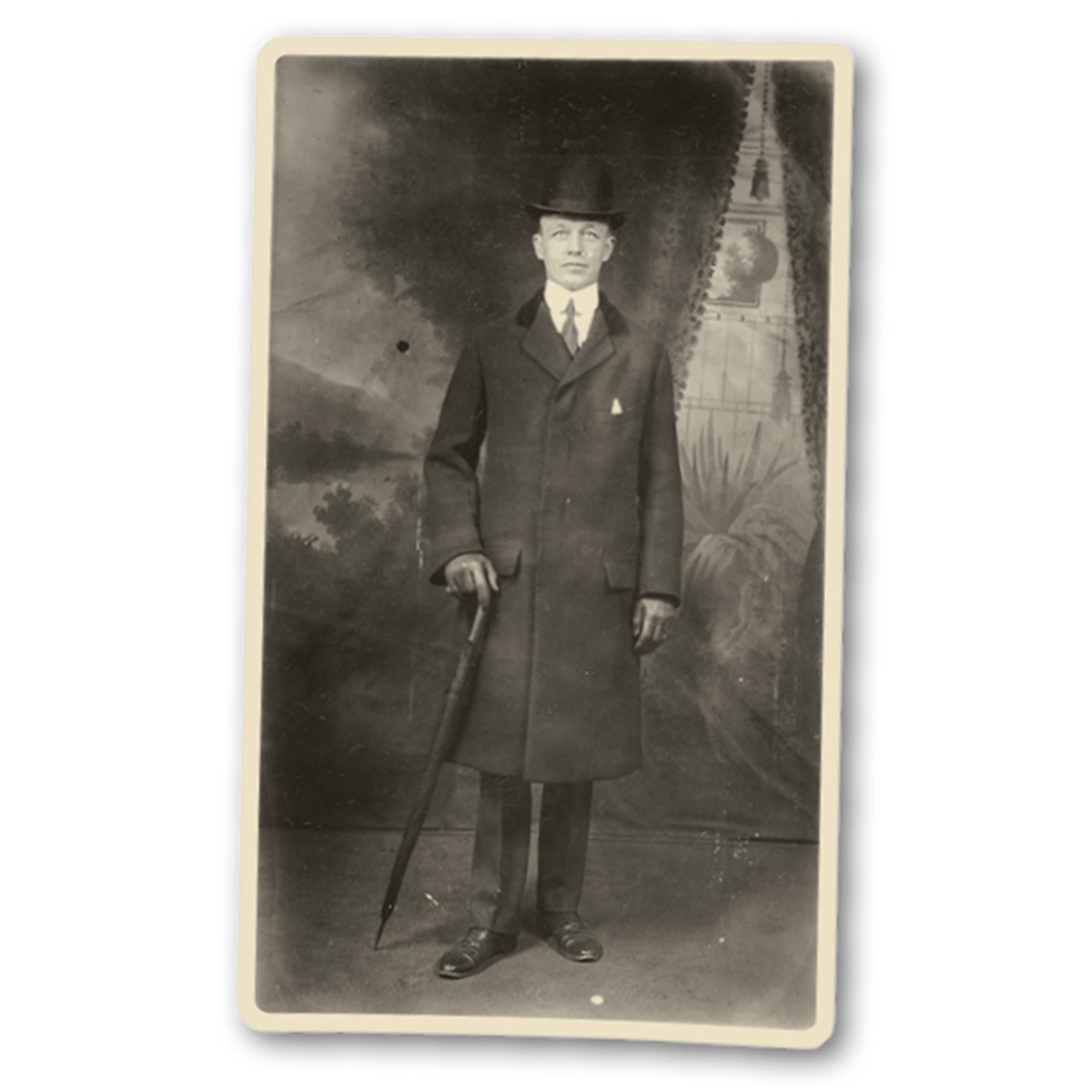

The preservation of the house was the vision of the eccentric Charles Gibson Jr., who lived there with his mother after his father, Charles Sr., died in 1916. As he watched the neighborhood decline during the 1930s following the Depression and his mother’s death, Charles Jr. tried to maintain the appearance of lost Boston opulence, dining regularly at the Ritz-Carlton in top hat and tails into the 1950s. Perhaps to honor his mother and Boston’s fading Brahmin heritage, he was determined to safeguard every aspect of his family home, forcing his guests to eat in the stairwell so as not to disrupt the dining room that, to this day, is set with Haviland Limoges china, as his mother left it.

Today, the property is overseen by the Gibson Society, which Charles Jr. founded for that purpose before his death, in 1954.

Charles Gibson Jr. / Photograph courtesy of the Gibson House Museum