Landmark: The Cutler Majestic Theatre

One of the city’s few great examples of Beaux-Arts architecture, the renovated Cutler Majestic Theatre is enjoying a vibrant second act. / Photograph by Bruce T. Martin

Modern-day theater-goers marveling at the Cutler Majestic have the unique pleasure of seeing it just as Isabella Stewart Gardner would have when she attended the theater’s opening night in 1903. Before the curtain rose for the musical comedy The Storks, Gardner would have observed the same elaborate details of the Edenlike atmosphere, including the theater’s ceiling, designed to resemble a heavenly trellis with patches of blue sky.

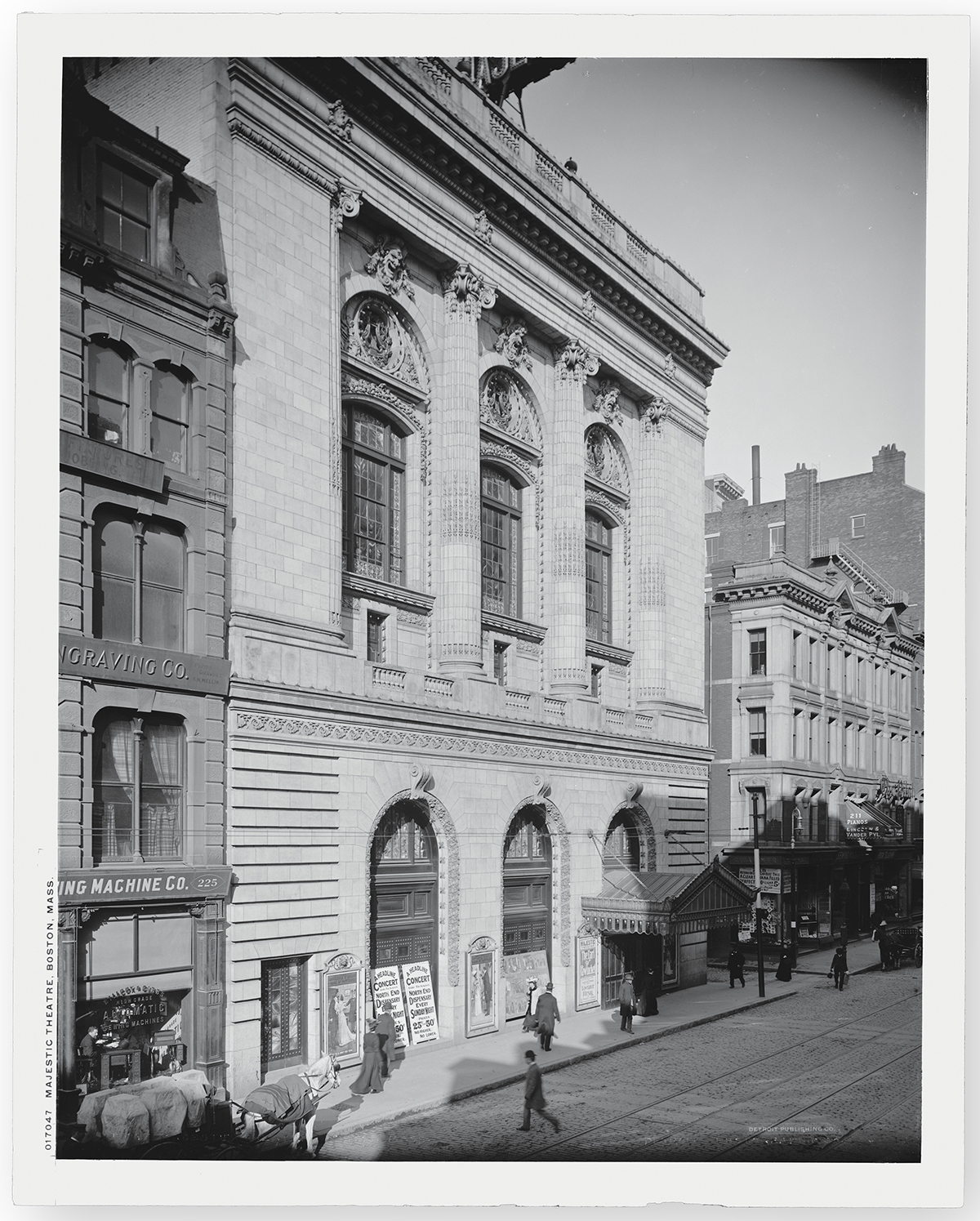

The Cutler Majestic Theatre is the work of architect John Galen Howard, one of the few Americans to attend Paris’s L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in the late 1800s. The Chelmsford native decked out his only known Boston work with all the classical references that characterize the Beaux-Arts style. As such, it is one of the city’s few great examples of Beaux-Arts architecture, along with the Boston Public Library and South Station. Today, a signature green placard near the building’s entrance announces its significance as a Boston Historic Landmark.

The 1,186-seat theater was commissioned by Eben Dyer Jordan, son of the founder of the Jordan Marsh department store empire, who was an active patron of Boston’s arts institutions. Just three years after opening it, Jordan sold it to the Shubert brothers—then the region’s premier theater operators, who ran everything from boxing matches to vaudeville shows there until 1956, when Sack Theaters converted it into a movie theater.

A photo of the Cutler in the early 1900s.

When it was built, the Majestic was the first theater in Boston to include electric lighting from the outset; other theaters had be retrofitted from gas to electric. Clearly fascinated with this “safe” source of illumination, Howard integrated the electric light bulb into his design, intertwining strings of bulbs with plaster grapevines along the ceiling’s trellis design, lining balconies, and highlighting the theater’s arches. Some 4,500 bulbs give the interior a fantastic glow.

On the exterior, hundreds of additional bulbs mounted in rosettes once lined the carved terra cotta arches as well. “[The façade] is part of creating this sense of arrival, this sense of grandeur,” says architectural historian Amy Finstein, who lectures at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. “When people saw the theater, suddenly they thought, ‘Whoa, this is bigger than me.’ They [knew that they had] arrived at someplace important.”

Three additional arches frame a trio of Tiffany stained-glass windows flanked by fluted ionic columns. The theater’s splendor is further accentuated by intricate stone carvings of fruit atop each window, surrounding three theater masks depicting happiness, sadness, and anger.

From the beginning, the Majestic has been heralded for its impeccable acoustics. Whether ticket holders pay top dollar (for seats like Gardner’s) or retreat to the balcony, they enjoy crystal-clear sound, thanks in part to the auditorium’s inverted bowl shape. Curving both out and up from the stage, it carries sound evenly across the space. Cantilevered balconies, another innovation, allow for unobstructed stage views from every seat in the house.

Gilded decorative plaster and rich handcrafted accents abound, which earned the theater the nickname “House of Gold” early on. The lobby is adorned in a reddish-orange faux marble called scagliola, as well as murals by William de Leftwich Dodge, an artist known for his work in the Library of Congress and the Boston Public Library.

The theater was saved from the wrecking ball by Emerson College in 1983; five years later, the college launched a $14.8 million restoration project. Reopened in 1989, it was eventually renamed the Cutler Majestic in honor of Ted and Joan Cutler. The Cutlers funded the final phases of the project, overseen by Elkus Manfredi Architects and unveiled in 2003. The theater’s marquee is one of the only parts of the building not originally drafted by Howard.

To enjoy a truly authentic experience, book a seat in rows C or D of the center balcony. Made up of original seats from the orchestra level, they include a small hook and rack below—once used to hold canes and top hats. The Cutler is much the same today as it was a century ago—Mrs. Gardner likely wouldn’t spot a difference.