New England Made: Element of Design

Rhode Island’s O&G Studio brings a “wood-first” approach to furniture making.

Photograph by Pat Piasecki

To the casual observer, O&G Studio crafts beautiful, handmade wooden furniture from the bayside town of Warren, Rhode Island. But look closer: Not only does the Ocean State company design and build seating, tables, mirrors, hardware, and lighting, it also operates a nearby showroom, offers consulting services to local manufacturing companies, and runs an intensive apprenticeship program—all while lending a chunk of its staff to the Rhode Island School of Design’s faculty.

Co-owners Sara Ossana and Jonathan Glatt say that O&G’s plethora of undertakings is a natural progression of the pair’s obsession with design (plus a shared streak of perfectionism). Ironically, when they met as graduate students at RISD in 2002, they were studying everything but furniture design—Ossana pursuing a degree in interior architecture and Glatt in jewelry making—until both ended up in an intensive, six-week furniture-welding class. “I don’t think either one of us actually designed a piece of furniture for two years after that,” Glatt says. “But as our careers progressed in our respective fields, we started to have more and more crossover with furniture.” Eventually, the two decided to switch gears and launched O&G in 2008 with a line of Windsor chairs. A decade later, the company still focuses on chairs, but enjoys a worldwide following for all of its product lines.

O&G’s sunny workspace—20,000 square feet of spare parts and sawdust—is a testament to its “wood-first” approach. “Because it’s alive, wood is a perfect combination of control and craft,” Ossana says. “Once you cut the tree down, the wood keeps moving—you have to work with it in the right way and respect it, but also celebrate it.” That translates to what Glatt calls “wood engineering,” or carefully assembling a product based on the material’s structural properties. Throughout the building process, workers handselect each piece of wood according to its grain, which determines everything from strength to how dark a product can be stained. For O&G, that also means performing most of the building by hand. “There’s too much variation in wood that just doesn’t work with machines,” Glatt says, “but the human hand can pick up and adjust for all those little tiny variations. It’s a hand process all the way through.”

A builder fits a rail onto an “Athenaeum” settee, O&G’s most complicated build. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

“We wake up in the morning wanting people to be as passionate about design and making as we are,” Ossana says. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

A chair arm, handcarved by one of O&G’s master craftsmen. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

In the studio’s sanding area, a craftsman finesses all the pieces until they’re as smooth as “melted butter,” Glatt says. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

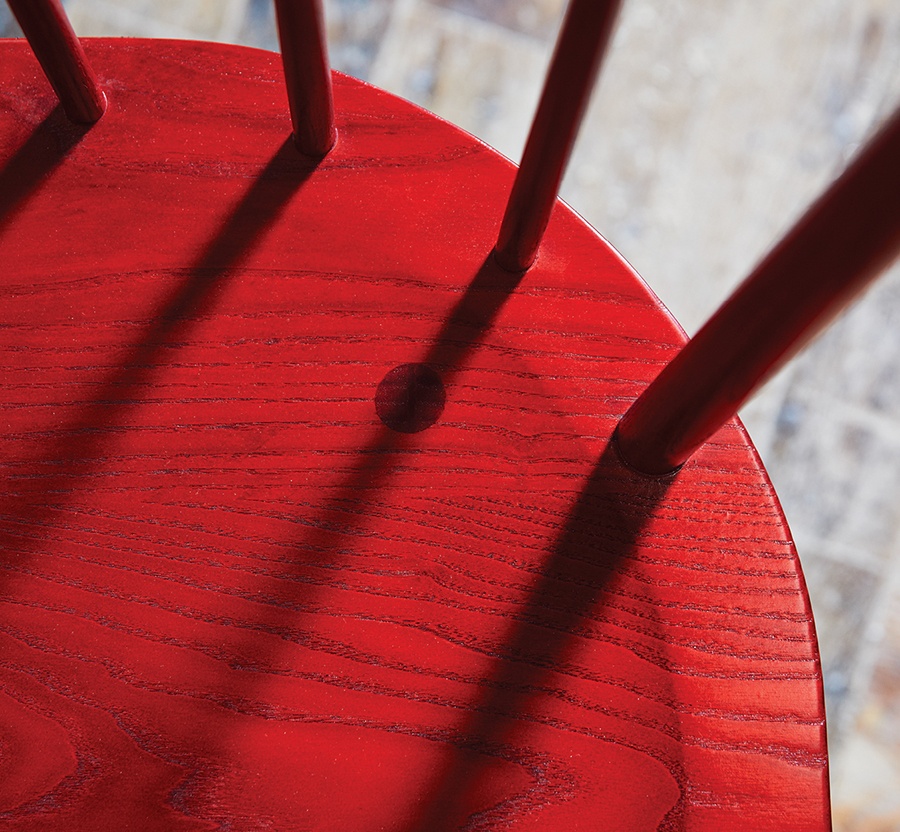

To make one of the company’s signature Windsor chairs, builders start with the seat. A craftsperson takes a slab of wood (O&G primarily uses North American ash, maple, and walnut) and forms the saddle shape by profiling the edges with a table saw, adding contours with a “dishing” machine, and finishing by hand. Once it’s shaped, builders select wood for the chair back and arms, making sure that growth rings run in the same direction (for both structure and aesthetic). The chosen pieces go into a steam box, where they’re steam-bent around custom forms and then put away to dry. Next, builders turn their attention to the legs and back spindles, shaping the pieces on a hydraulic lathe before gluing and wedging them into place sans hardware. “This keeps with the traditional Windsor style, which didn’t utilize nails or screws,” Glatt says. Builders handcarve any piece that needs extra attention and then send the chair off to be sanded and stained. Each piece receives five to seven coats of one of O&G’s 19 signature finishes, which range from barely there translucence (“Oyster”) to deep marigold yellow (“Turmeric”) to bright Mediterranean Sea blue (“Cyan”). The vibrant colors are a studio trademark: “We take longer to come up with a stain than we do a chair design,” Ossana says. “When you’re making chairs to last, you have to be really disciplined about how it’s done.”

O&G’s team of 17 builders puts out 100 to 150 pieces a month, with products shipping everywhere from Shingle-style homes in New England to sleek boardrooms at Facebook, Instagram, and Google. The company’s wide variety of clients points to the adaptability of its products: a characteristic both business partners say they sought to bring to the design world. And now, with buyers across the globe, it’s a sign that they’re doing something right. “I still wake up and I think, ‘Oh my god, this is working,’” Glatt says. “But that’s part of it; you gotta believe in it and look at what your resources are, and every day you just plug away.”

“You kind of get bullied by natural materials,” Glatt says of the company’s reliance on wood. “Not every woodworker can do it!” / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

Cofounders Jonathan Glatt and Sara Ossana. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

An “Athenaeum” settee, a “Colt” side table, and a “Tiverton” lamp on display. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

A builder preps a steam-bent ash comb for a “Colt” chair. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki

A chair stained in bright-red “Bayetta.” Staining is the studio’s only proprietary process, Ossana says. Each color can take up to a year to develop. / Photograph by Pat Piasecki