When Flattening the West End Was Just a Dirty, Dangerous Summer Job

“I nearly collapsed the first day,” says Colliers International CEO Tom Hynes.

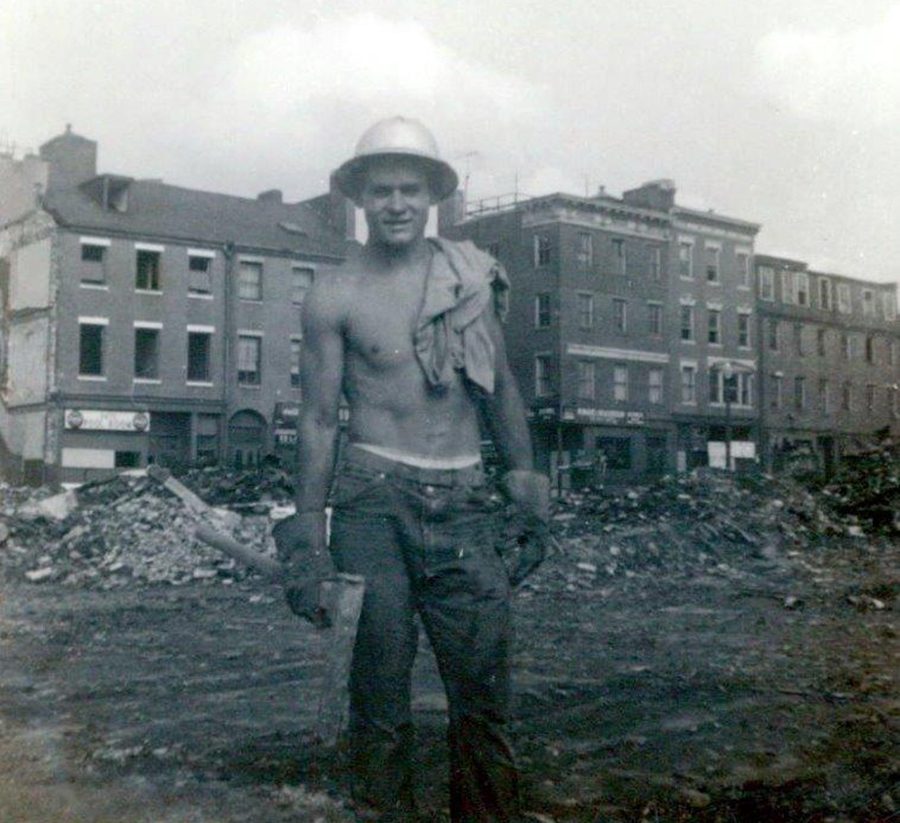

Tom Hynes during the West End demolition in 1959 / Photo provided by Tom Hynes

When Tom Hynes walks around Boston, he can point to buildings he’s brokered deals in. At the Prudential Center, he secured space for the headquarters of high-powered law firm Ropes & Gray. In the Fenway, he sealed the deal on 550,000 square feet of office space for Blue Cross Blue Shield. Looking around the West End, though, he can recall not what he’s created, but what he demolished.

Before Hynes, nephew of mayor John Hynes, became the CEO of real estate firm Colliers International, he was a student at Boston College looking for a summer job. He found one with Duane Wrecking Corp., and in June 1959, Hynes joined the demolition team that would wipe out the West End.

He’ll speak about his experience on the demo crew this Thursday at the West End Museum. In a talk titled “The West End Demolition Through the Eyes of a Young Construction Worker,” Hynes plans to describe the exhausting work he did some 60 years ago, during one of the most controversial urban renewal projects in U.S. history.

The word he repeatedly uses to describe the work? Backbreaking.

“I nearly collapsed the first day,” he says.

Hynes was assigned to some of the project’s most dangerous jobs, like plucking scrap metal from giant piles of rubble. To raze the buildings, bulldozers would push all of the debris from a week’s worth of demolition into one city block, then torch it all. “So you have this massive inferno with acrid smoke and who knows how much hazardous waste in it,” Hynes explains. Meanwhile, gasoline and kerosene caused muffled explosions in the wreckage, while bulldozers continued to add more debris to it. Hynes was tasked with pulling steel and iron—like pipes and cast-iron radiators—out of the pile as it grew larger and larger.

“The drama was the bulldozer driver can’t see or hear you,” Hynes says. “You’re on your own, so you make sure you look out for yourself.”

Without any safety precautions, he stood in trucks while cranes dropped debris into them, and spent hours packing salvaged bricks into huge steel buckets.

“After two weeks of working like that, I started to actually get physically adjusted and in good shape. And by the middle of the summer I was like a rock,” Hynes says. So he stayed. For years.

The West Roxbury native spent several summers and all of his college breaks and holidays making extra cash with Duane, raking in $2.10 per hour. He stopped after five years, when the hazardous environment he’d begun to grow comfortable in claimed a coworker. While working on top of a small garage, a man driving a small bulldozer next to Hynes was killed after the bulldozer went off the roof.

Hynes traded his hard hat for a helmet, and became a second lieutenant in the Army. Later, in 1965, Hynes found himself in the boardrooms of commercial real estate firm Meredith & Grew. He’s been with the company since then, becoming vice president, then chairman. Meredith & Grew changed its name to Colliers International in 2011, after joining with Toronto-based Colliers in 2008.

Photo via Tom Hynes / West End Museum

Aside from his summer job, Hynes had a family connection to the West End project. His uncle was mayor John Hynes, who created the Boston Redevelopment Authority and put the plan to raze the neighborhood in motion. But Hynes didn’t sign onto the demolition crew at age 19 because he explicitly agreed with the plans for the area. “My viewpoint was that of a college kid trying to, one, stay alive, two, make some money, and three, get in shape for football.”

The urban renewal project that was meant to create the “New Boston” displaced almost 3,000 families, replacing brick rowhouses with high rises, government buildings, parking lots, and offices. By the time Hynes arrived on the job, most of the original West Enders had already left their homes involuntarily, save for one holdout who refused to move.

Hynes says he had “certainly more than a passing curiosity factor about what was going on.”

“But I had no real good frame of reference for it. Urban renewal was new. It was the hope of the future for cities in the country,” he says. “Today you have much more mitigation and much more sensitivity to the whole process.”

Boston’s erasing of the West End is widely considered one of the country’s most infamous examples of urban renewal. And Hynes has had a lot of time to think about the project in the years since working for Duane.

“I go to the dentist right there,” he says of the neighborhood. “So every time I go down there I think about the site. I think about what didn’t happen and how it could have been better, or if it should have happened at all.”

But, for the record, he doesn’t feel guilty about helping to tear down almost a third of the city.

“I have no reason to feel remorse. I didn’t start the project. I didn’t die. I’m thankful that I had a job, I survived, and that I made a little bit of money,” he says. “Looking at it from a different perspective, could it have been done differently? Sure. Sixty years later and there are still very, very strong feelings from the residents. It was bad. It took their homes. How could they have positive feelings about that?”

With any project, Hynes says, planners have to consider the impact it will have on everything else around it, from stakeholders to personal property, and then work from that standpoint. It’s an approach he learned from that dangerous, dirty summer job in college, and one he has kept in mind during his time in the real estate business.

“[My] hard work [in the West End] was the incentive not to do that for a living, but to get to the next level and help shape the future of the city.”

Hynes will recount his memories of the demolition of the West End this Thursday, December 6, at 6:30 p.m., the West End Museum, 150 Staniford St., Boston, westendmuseum.com.