Discover the History behind Horticultural Hall

A one-time gathering place for growers and the current HQ of Boston magazine.

An exterior view of Horticultural Hall soon after its 1901 debut. / Photo courtesy of Detroit Publishing Co./Library of Congress

We’ve seen plenty of trend pieces about millennials’ love for plants. But today’s tenders of massive monsteras have nothing on the green-thumbed enthusiasts of centuries past, who preserved plant specimens in herbariums, painted them in painstakingly detailed illustrations, and created sprawling botanical gardens and arboretums. They even designed architecture around flora—not only glass-walled conservatories and orangeries, but sturdy, stately structures such as Back Bay’s Horticultural Hall, the former headquarters of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (and current HQ of the magazine you’re reading right now).

The society didn’t start out with fancy digs. Its first meeting convened at a Congress Street insurance office on a frigid February day in 1829, when 16 attendees braved 6-foot snowdrifts for the occasion. Despite that modest turnout, the society quickly took root, hosting exhibitions of locally grown flora (including buzzy new cultivars like the Concord grape) and helping to create America’s first garden cemetery at Mount Auburn. By century’s end, the society claimed nearly a thousand members and had outgrown two previous Horticultural Halls—the first on School Street, and the second on Tremont—neither of which remains standing today.

The third Horticultural Hall was built to last. After purchasing a lot on the corner of Mass. Ave. and Huntington, the society hired Wheelwright & Haven, the architectural firm behind landmarks such as the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall and the quirky Harvard Lampoon Building. Horticultural Hall would be a more sober structure, one designed to harmonize with the year-old Symphony Hall across the street. The resulting blueprints begot a rectangular Renaissance Revival building of brick bedecked with white trimmings, like a layer cake artfully adorned with icing. Bedford limestone framed the windows and formed Ionic capitals atop the pilasters; marble friezes featured fruits and flowers, hinting at the bounty within. Inside, the ground floor contained a 300-seat lecture hall, a small exhibition hall, and a cavernous main exhibition hall measuring over 52 feet wide and 123 feet long. Vaulted skylit ceilings soared nearly 50 feet high, and a raised loggia at the hall’s eastern end let viewers survey the vast space. The second floor held another stunner: a balconied library boasting ornate woodwork and more than 10,000 volumes on horticultural topics.

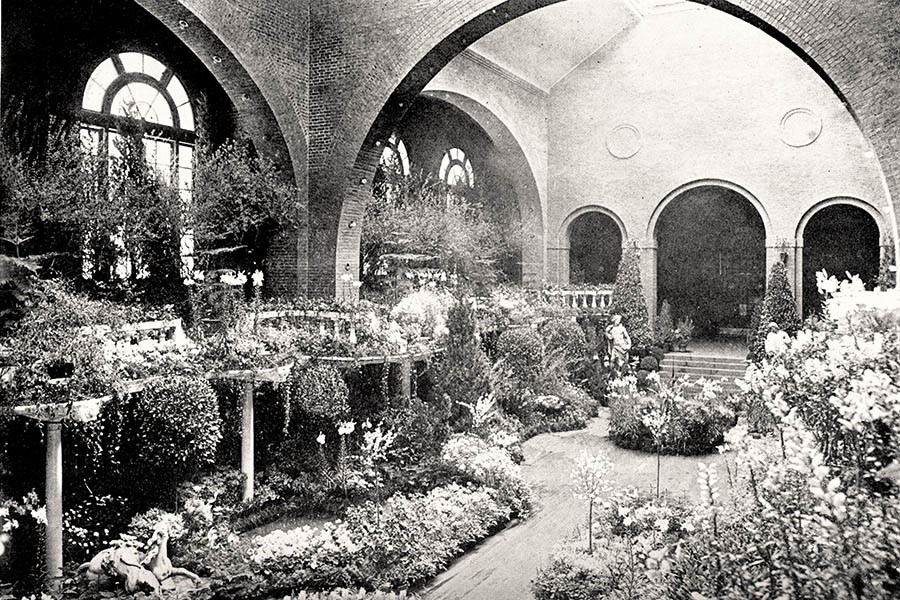

More than 150 species starred in this Italian Garden exhibition in the spring of 1912. / Photo courtesy of the State Library of Massachusetts

On June 3, 1901, when 2,000-plus attendees arrived for the opening night of the inaugural 10-day show, they found the new building filled with flowers and foliage loaned by Greater Boston’s finest gardens and greenhouses. White and purple wisteria bloomed in the lecture hall; jasmine perfumed the loggia. The small exhibition hall showcased a thousand orchids, a collection called the “best ever gathered in America” by the Boston Transcript. And in the main hall, a riot of azaleas and rhododendrons offered the illusion of a real garden transported indoors, complete with floors covered in earth and gravel walkways.

This arched entrance was added to the building during the 1980s renovation.

In the decades that followed, Horticultural Hall served as a home not only for the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, but for lots of other like-minded groups, including the Wildflower Society, the Garden Club Federation, the Boston Mycological Club, and the Herb Society of America. The building was also rented for an array of other happenings, from dance parties to dog shows, antique fairs to Shakespeare performances. But it began a second life in 1984, undergoing a $4 million renovation that allowed the society to continue to operate the library while commercializing most of the building. The very first tenant: Boston magazine. The staff moved into one of the city’s most beautiful and unusual office spaces, which had been updated with a cantilevered mezzanine level that added square footage but preserved the hall’s grand scale and natural light.

In the ’90s, the society sold the building and transplanted itself to the Gardens at Elm Bank, a 36-acre property in Wellesley and Dover where it remains to this day. But that lavish library hasn’t gone to waste. Today it’s home to the Museum of Fine Arts’ William Morris Hunt Memorial Library, where books on art, not botany, line the shelves. And in the adjoining hall, monthly, quarterly, and biannual magazines continue to be made in that airy, sunlit space where annuals and perennials once bloomed.