Take a Glimpse into Beacon Hill’s Newly Renovated, Century-Old Synagogue

After more than a year of work, the 100-year-old Vilna Shul was about to host its grand re-opening—until COVID-19 forced them to close.

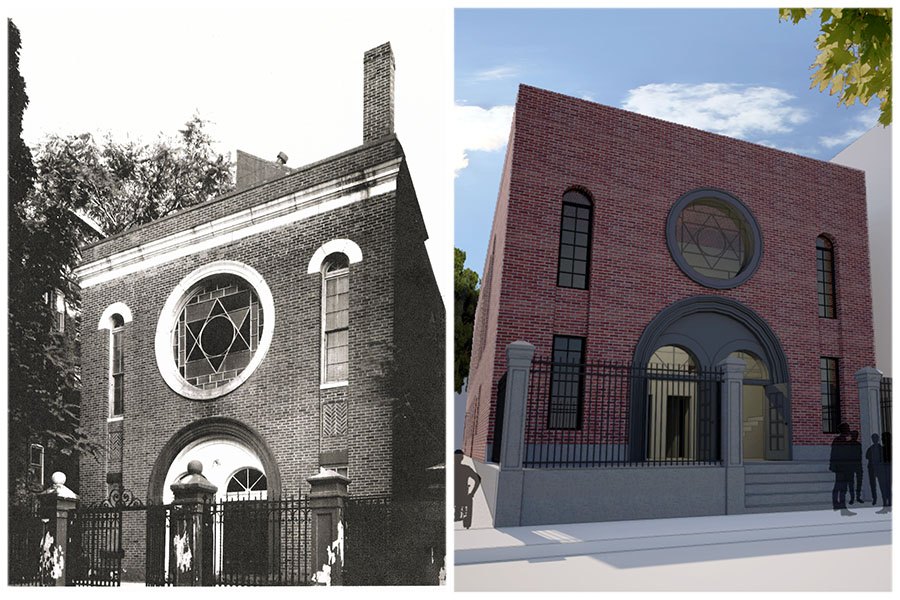

A 1920 photo of the synagogue vs. a 2020 rendering of the renovated cultural center. | Photos courtesy of the Vilna Shul

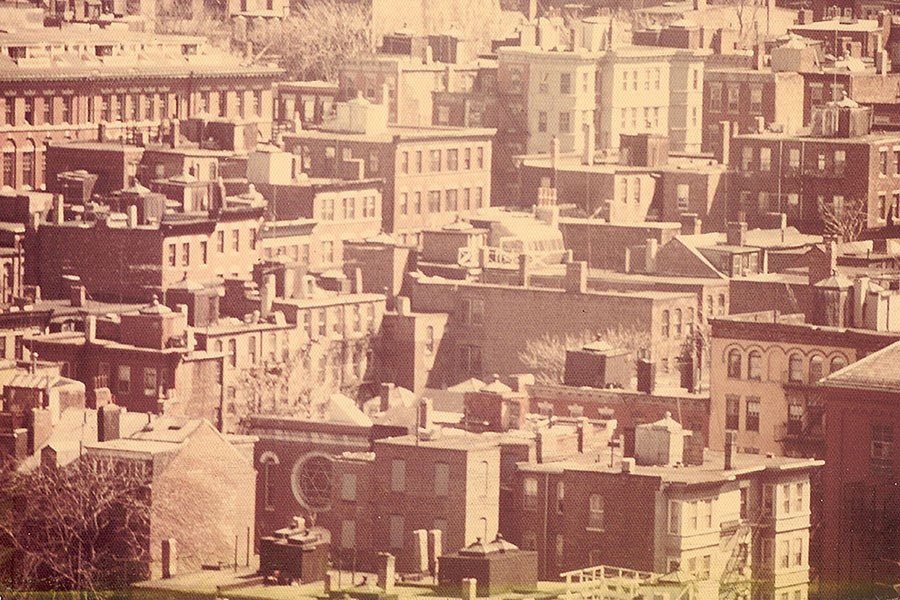

Look at an old photo of Beacon Hill, and even in sepia tones you’ll be able to pick out the Vilna Shul by its prominent round window filled by a stained glass Star of David. If you strolled through Beacon Hill and the neighboring West End 100 years ago, you’d have counted more than two dozen synagogues populating the cobbled streets. Make the same trek today, though, and due to the infamous Urban Renewal efforts of the 1950s, you’ll find that the Vilna Shul is the only one remaining from that period.

And this year, a century after its historic construction in 1919, downtown Boston’s last immigrant-era synagogue building—that is, one that was built during the swell of immigration to the U.S. in the early 1900s—got a major facelift. After 15 months and $4 million of renovations, which included an updated community room, 1,000 square feet of new space, and complete handicap accessibility, the place of worship-turned-Jewish cultural center was slated to host its grand re-opening this May—until the coronavirus outbreak struck and all scheduled plans went out the window.

Having to lock up the building instead of proudly opening the doors was disappointing, says executive director Barnet Kessel, but the Vilna Shul community was built on resiliency, and they deftly pivoted to a “Virtual Vilna.” The platform offers online programming such as meditation classes, challah-making workshops, and discussions on the Netflix television show Unorthodox, which have helped grow the community by attracting virtual visitors from Chicago to Costa Rica. They even digitized their annual fundraiser, which took place on June 4

“It seems like every week we’re drawing a parallel to the flu pandemic of 100 years ago, and finding sort of a comfort that they were able to survive as individuals, as a community, and as a congregation, and thrive after. So we’re finding motivation that we’ll be able to get through this, and thrive after, too,” says Kessel. For now though, the Phillips Street building sits empty, and, he says, “We’re just so anxious for people to get in the building and see what it can do.”

Photo courtesy of the Vilna Shul

Kessel hopes to host an official unveiling sometime in the fall, but when the lockdown lifts, the revamped Vilna Shul is brimming with good reason to make the little-known institution one of your first destinations. One such motivation is a recently gifted painting by modernist Hyman Bloom, a Boston artist whose work has hung in the MFA and MoMa, and who attended the Vilna Shul with his family as a child. After going through painting after painting with Stella Bloom, Hyman’s widow, in her New Hampshire home (“I felt like a kid in a candy store,” Kessel says), he eventually chose a colossal oil on canvas portrait informally dubbed “Rabbi Seated With Torah and Blue Prayer Book,” which will be a focal point in the revitalized cultural center.

Beyond enticement for art devotees, the building has plenty to offer lovers of antique architecture, too. Despite the recent slew of renovations, the second story sanctuary is still a century-old sight to behold. Towering ceilings, original arched windows with blue and red stained glass panes, a chandelier sourced from a hotel that was going out of business back in 1919, and even gas lamp fixtures (which the founders installed “in case the electricity thing didn’t last,” says Kessel) help the room reverberate with history. Dozens of pews populate the floor, which tell a unique Boston story of their own: The Vilna Shul was first located down the street at the original site of the Twelfth Baptist Church, until the city claimed it via eminent domain and, in 1919, the synagogue moved to its present-day 18 Philips Street home. But they brought the pews, which members of the historically black 54th Regiment once sat and prayed in, with them. The rare relics of African American and Jewish history have now been brought back to their former glory, thanks to wood refinishing and the modern addition of plush cushions.

A refinished pew, relocated from the original site of the Twelfth Baptist Church and one-time home of the Vilna Shul. | Photo by Sofia Rivera

There is also one integral part of the grand prayer sanctuary that will actually go back in time, in the next phase of the restoration plan. The walls, covered in peeling paint, will be carefully peeled even further to reveal what they looked like a century ago. When the synagogue was first reclaimed as a cultural center some 25 years ago, the space was covered in beige-yellow paint. Soon after, a revelation was made. Beneath the neutral hue were three distinct murals, painted by the Lithuanian Jews who attended the synagogue in the 1920s-1940s. So far, the uncovered gems peek out from the yellowish walls like snippets of a story: the base of a column (a piece of the earliest mural), a corner of the Star of David, a fragment of a flowery Art Nouveau scheme. As solutions are painstakingly applied to reveal the pictures beneath, each phase of mural will be photographed for the archives, until the full scope of the first scheme is unearthed.

Downstairs, the recent renovations led to surprising discovery. In the midst of excavating 1,000 square feet of dirt-filled space, the team found a shoe. Then, another shoe, and another. In all, about eight single pieces of footwear had been hidden in the walls, adding to a cross-continental phenomenon where concealed shoes are found in old buildings, thought to be left there as a symbol of protection. “We found a lot of interesting things in this huge space,” Kessel says, hinting at fodder for a future exhibit. And before they sealed off the new walls, they made sure to keep with tradition and tuck a few shoes behind them.

The center’s previous museum vs. the freshly painted community room, ready to host the first full exhibit in the renovated space. | Photo by Sofia Rivera

In addition to being a cultural institution, Kessel says the Vilna Shul hopes to step into this next era as a small gallery and as a community-building force, encouraging visitors to unite around differences. “The weight of being the last immigrant-era synagogue building in Boston is huge, and making it so that more people can come through this building and learn a bit about the culture, the faith, and make it less ‘other’ is for sure a part of our modern mandate,” he says. “Equally as important is the way people can compare that story with the stories that are happening right now.”

When the Vilna Shul eventually reopens its doors, it will actually be the second time they’ve celebrated their 100-year anniversary. Since “1919 is on the cornerstone, but the building didn’t open until 1920, we get to celebrate our centennial twice,” Kessel explains. “Just like they got into the building in 1920, now we’re getting back into the building in 2020.”

This commemoration, though, will mark the milestone with a concrete time capsule, which will be buried near the old front door. When the city dwellers of the future open the case, they’ll discover artwork, a sealed letter from the president of Harvard, and even a couple of modern shoes, among other symbols of life in 2020. Without repainting the walls, the capsule will paint a picture of what the community valued today. In that sense, it’s a new mural for this new era of the Vilna Shul.

An already unearthed and restored mural in the prayer sanctuary, showcasing an estimated 98 percent original paint. | Photo by Sofia Rivera

Photo by Sofia Rivera