Living Monument

Isabella Stewart Gardner’s former Brookline residence stays true to its origins while accommodating its present-day inhabitants.

Dentil moldings, wainscoting, and interior window shutters nod to the home’s 19th-century origins, while a sumptuous new rug from Landry & Arcari takes color cues from the Gracie wallcovering. / Photo by Michael J. Lee

Isabella Stewart Gardner, Boston’s most famous patron of the arts, relished the time she spent at Green Hill, the 40-acre Brookline estate she and her husband, John, inherited from his parents in 1886. Built in 1806, the sprawling, Federal-style, vine-covered manse was perched atop a sloping hill amid verdant lawns and fields where Isabella, a passionate horticulturalist, saw limitless potential for cultivation.

Isabella’s primary residence was in the Back Bay—and later in Fenway, where she constructed the Venetian palazzo of her dreams that has housed her eponymous museum for the past century—but from April through October, for more than 30 years, Green Hill was home. In the decades she lived there, Isabella, along with the property’s lead gardener, Charles Montague Atkinson, transformed the landscape of Green Hill, says Shana McKenna, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum archivist, from a pastoral farm to a series of lush and elaborate gardens that received wide acclaim.

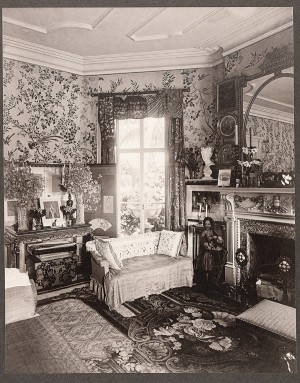

In Isabella’s day, the parlor was filled with art and other decorative collectibles that had personal meaning to her. / Photo courtesy of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Isabella made changes to the interior of the house as well, adding a two-story glass conservatory and a music room where small concerts were held. “Very quickly, Green Hill became this spot where she entertained artists, musicians, and writers,” says McKenna, noting that the home remained a summer haven for the extended Gardner family. “Guests and friends came to see Isabella’s art collection, to listen to music, and to see the flowers.” A voluminous guest book contains inscriptions from Isabella’s Green Hill visitors—who included novelist Henry James, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and writer and activist Julia Ward Howe—often with sketches, sentiments, and inside jokes referring to something that transpired during their visit. This preserved history nods to how much Isabella enjoyed the estate. Says McKenna, Green Hill was also a place where Isabella took refuge, “seeking solace when she suffered loss or struggled with illness.”

Isabella endured her first of a series of strokes in 1919 and could not make her annual respite to Green Hill. Before her death in 1924, she sold the home to her nephew, George Peabody Gardner. “While the property was subdivided several times afterward, the home remained in the Gardner family for 172 years, which is pretty amazing,” McKenna says. In 2011, it was purchased by the current owners.

Built in 1806 by Captain Nathaniel Ingersoll of Salem, the estate was purchased by John Gardner and his wife Catharine in 1842 as a summer home for their growing family. The acreage featured a small farm and several greenhouses where John Gardner grew fruit and prize-winning orchids. / Photo by Richard Mandelkorn

Boston photographer Thomas E. Marr took this exterior shot of the house (and the above photo) in 1905. / Photo courtesy of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Shortly after buying the house, the homeowners embarked on a renovation that included lifting the house off the ground to have a new strong foundation built by Youngblood Builders. Aside from structural and system updates, the interior needed to be more suited for contemporary living, says architect Dell Mitchell, “Yet they were very conscious of preserving what was worth preserving.” Among these were the main stairway’s handcarved balusters and banister finials and the grapevines that climb along the home’s façade.

“It was very much a house from a previous era in the way it was laid out,” Mitchell says. “There were rooms geared for large-scale entertaining and a rabbit warren of small rooms with nothing special going on that must have been servants’ quarters long ago.” Mitchell and her team opened the layout to make the connections between the informal and formal areas of the house more natural.

Another key aspect was refocusing the interior to engage with the surrounding landscape. “The house was very interior oriented,” Mitchell notes. “It wasn’t focused for the way people live today, where people really enjoy comings and goings and their backyards where kids play.” While there was a carriage house on the property, it wasn’t practical by today’s standards. A new driveway was created that leads to the back of the home, where an attached two-story garage leads into the kitchen, which, thanks to the addition of several windows, is swathed in light and views of the new terraces that emulate the original terrace gardens that were there in Isabella’s time.

The kitchen is airy and bright and filled with all the modern conveniences, yet the white palette keeps it anchored to the home’s origins. / Photo by Richard Mandelkorn

In the office, walls are sheathed in wool flannel and flat Roman shades have a masculine feel. The Linley game table procured in London is paired with chairs upholstered in purple velvet. / Photo by Michael J. Lee

The homeowners hired Kate Bellin to help them curate art; most pieces were created by midcentury American female painters, a choice that might have resonated with the pioneering collector Isabella. Interior designer Dee Elms came on board to refresh the living room and office after they’d lived in the home for many years. The office, located off the foyer, flows into the living room, so it was important to establish cohesion between the spaces while also giving each room its own identity and some modern styling.

“These rooms really show how you can mix classic and contemporary forms,” says Elms, who added a sculptural European chandelier in the office where original moldings have been restored and replicated. A larger rug unifies the space, which is also used as an overflow room for parties and family card games, which happen around a handmade game table paired with purple velvet chairs.

The living room’s Gracie wallcovering—a handpainted motif depicting flowering trees and birds based on Georgian-era wallcoverings—was selected for its resemblance to a wallcovering that sheathed the walls during Isabella’s era. Elms added soft cream drapes to frame the long windows and, at a Parisian gallery, discovered the room’s centerpiece: a mod chandelier made of ivory and pale-green glass. The carved fireplace surround is original. While the piano is a modern-day addition, it’s easy to imagine a similar model in the room a century ago when Isabella hosted one of her lively salons.

First published in the print edition of Boston Home’s Winter 2024 issue, with the headline “Living Monument.”