New York Times Wine Critic Eric Asimov Dishes on His New Book

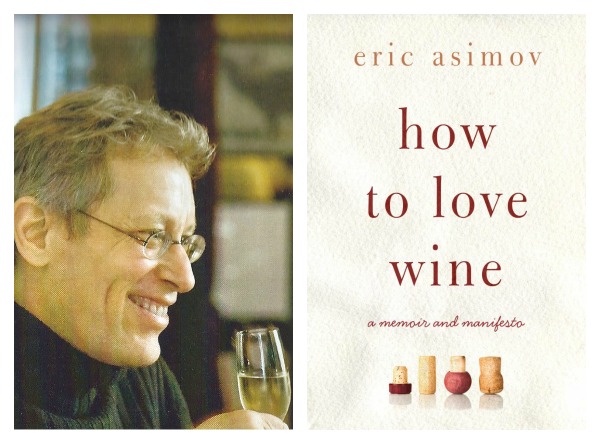

Asimov, left; his new book, right. Both images courtesy of Facebook.

Asimov, left; his new book, right. Both images courtesy of Facebook.

Eric Asimov, Chief Wine Critic of the New York Times, a title he admits is “ominously highfalutin,” has been tweaking and tailoring his distinctive voice during the span of his almost-thirty-year tenure. Influenced largely by his critical predecessor, Frank Prial, Asimov takes a practical approach to wine that emphasizes cultural and social context over rote memorization from books or standard journalistic tropes like scores and tasting notes. His new book, How to Love Wine: A Memoir and Manifesto, is a celebration of the refreshing new attitudes of the twenty-first-century connoisseur and an exploration of the real factors that lead to an enduring love of wine.

Tomorrow, Asimov will be discussing his book at the Harvard Book Store at 6 p.m., and will be at Belly Wine Bar in Kendall Square afterwards for an after-party and book signing from 9 p.m.-12:30 a.m. Tickets for the Belly event are $15 and include plenty of eclectic wine, chosen by co-owner Liz Vilardi. In the meantime, read on as Asimov discusses White Zinfandel, craft beer, and the role of the sommelier in our Q&A.

What was your motivation in writing How to Love Wine?

EA: Two main motivations. First, and I say this in the book, is that one of the main reactions I get from the public, more than any other, is people reporting how anxious wine makes them feel. They tell me, “I like wine, but I don’t get all those aromas and flavors that critics talk about. I guess there’s something wrong with me.” I’ve heard this so often from people that it began to be personally painful for me that something as benign and pleasurable as wine was causing so many people to feel intimidated or anxious. Combined with the fact that this is the greatest time in history to be a wine lover. There are more great wines available and more styles from more different places than ever before. This combination of potential pleasure and these obstacles required an examination of our wine culture to see why people were feeling this way. This is what I came up with.

One of the bottles you credit with inspiring your passion for wine was the much-maligned Beringer White Zinfandel. Why was that a seminal moment for you?

Well, it wasn’t so much the wine itself, but the synergy between what we were eating (garlic butter shrimp over linguine) and the wine. It was just so good together that I wanted to continue having that experience. Obviously my palate wasn’t so developed at the time that I would have recognized what might have made that wine insipid. But it inspired me to want to keep exploring and make that a priority in my life. You shouldn’t be humiliated by your first exposure to wine. I’m not humiliated by it. But I am frustrated by people who like White Zinfandel and who won’t try anything else.

In the book, you credit your very ordinary background, in regards to wine—one without extensive travel, haute cuisine, or access to great bottles—with how you approach the subject. How do you feel that’s benefited your writing and how the public responds to you?

It’s not that I went out to set myself off as different. It’s just that, in my case, getting into wine by drinking it everyday and having it on the table with food, I think has given me a different vantage point from many other writers who see wine as an almost fetishistic object; something to be exalted and worshiped and basically bowed down to. It’s just a food. It’s just a beverage. You shouldn’t confuse this with the idea that I’m trying to demystify wine or that I only like cheap wines. That couldn’t be farther from the truth. It’s just that wine, at its very basic level of enjoyment, is something that is on the table that enhances the pleasure of eating food. It enhances the social pleasure of eating with other people. It tastes good. And there’s no getting around it, the slight level of intoxication that it brings in moderate consumption is part of this. This is not to say that wine can’t be a profound and wonderful and unbelievably beautiful pleasure. It can be all of those things. You start out by incorporating it into your life. That’s another way of looking at it without burdening it with scores, which convey the idea that you must only shop for the so-called best. That you must search for greatness. That you must measure wine on one universal scale. It’s just a different way of coming at this very broad subject.

Why do you feel that longstanding publications like The Wine Spectator and The Wine Advocate are less influential than they have been in the past? Why has there been a “decentralization of critical thinking,” as you called it?

Far be it for me to say they’re irrelevant. That’s not true. They’re highly influential. But I think their influence, because of their scores and rating, is felt mostly in moving bottles. I do believe their influence is waning in training people how to think about wine. In a sense, they played a role in making themselves less relevant by doing such a good job of introducing people to wine and building enthusiasm. Many people have gone on to outgrow the need for a central authority that tells them what to buy and how to perceive wines. I think when you get to a certain point you’re looking for something else in critics, rather than simply steering you each year to a hierarchy of producers. This doesn’t go for everybody. The great mass of consumers isn’t so interested in wine that they’ll take on these responsibilities for themselves. For them, these kinds of consumer publications will always have an important role to play.

Do you feel that growing interest in food and dining has helped reshape wine’s image as a stodgy, intimidating beverage reserved only for the elite?

There’s no question about it! You’ve been seeing a food and wine revolution going on in this country for, I don’t know, I’m losing track, maybe forty years now, or more. And each generation approaches food and wine from a vantage of greater knowledge and comfort. So, I think you’re seeing younger people today who are growing up with wine because their parents introduced it to them. Then they move on further. People have become far more interested in good beer, good cocktails, good cocktail ingredients, good food ingredients, and good wine.

Will wine ever achieve the same momentum that craft beer is currently experiencing, particularly with the younger generations?

Absolutely! I think you can grow into it. It’s partly an economic thing. You can walk down to your corner deli and for ten bucks buy a six-pack of some of the greatest beer in the world. You can’t do that with wine. You’re spending more money. It requires a certain amount of disposable income. You also need the motivation to want to learn more. Anybody who is into craft beer has at least tried to read about it and to learn different styles of beer and different producers. Wine isn’t so different. It just requires some commitment.

In the book, you challenge almost every convention to approaching a bottle of wine, including blind tastings, vintage charts, and tasting notes centered on esoteric aromas. You go so far as to call them “parlor tricks.” These are typical skills practiced by people studying to become sommeliers. How do you rationalize that traditional education of the “experts” and what role do you think they perform?

It’s funny, I think about this a lot and when I’m in Boston I think I’ll be meeting a fair number of sommeliers. Sommeliers have a crucial role to play. I think they’ve never been more important than they are now. They’re one of the greatest resources for consumers, if they can make use of them. Like merchants in wine shops, they’re the interface of the wine industry. Sommeliers are there to inspire people. They can turn people off right away or they can turn people on. It’s a very complex question that you’re asking. But I think what you’re getting at is that I’m sometimes dismayed that sommeliers confuse their professional training with what consumers need to know to enjoy wine. We don’t need to know all this stuff about soil and where the oak comes from in the barrel regiment and whether you can identify wines blind and things like that. Those are just parlor games for professionals. I just think professionals, like sommeliers, just need to be able to communicate with the public in a language that they understand and that they find useful.

One of my favorite quotes from your book is “A great wine, even a good wine, has the capacity to surprise and to move, and perhaps even to scare.” Off the top of your head, what are some wines that have “scared” you?

(laughing) I don’t know if off the top of my head I can name any specific bottles, but sometimes you’re exposed to flavors or aromas that can be transgressive at first. I think that’s true of food as well. You have something that you find simultaneously attractive, yet repulsive. I think that’s a great thing to explore. You can also be moved in a way that can possibly be a little bit scary. I’m a little too tightly wound and rational, but I’ve seen people who just break into tears over a glass of wine. I love that and I wish my capacity for that was greater than it is.

For more online food coverage, find us on Twitter at @ChowderBoston