Taking Inventory: Behind the Scenes at M.F. Dulock Pasture-Raised Meats

Welcome to Taking Inventory, where we raid the spice racks, walk-ins, bar shelves, and tool arsenals of the restaurants and artisans in the Boston area.

Dulock hard at work at his shop in Somerville. All photos by Fawn Deviney for Boston magazine.

Dulock hard at work at his shop in Somerville. All photos by Fawn Deviney for Boston magazine.

Michael Dulock didn’t set out to be a butcher. In fact, most of his life’s work has been devoted to a different realm of the animal kingdom: fish. For two decades Dulock worked alongside his brother Steve, who runs Sunny’s Seafood, a fish purveyor that distributes to some of the best restaurants in the area. But five years ago, the Everett native set out for a different challenge. “Fish was very familiar to me, and when something becomes familiar it becomes less exciting,” Dulock says. “Knowing I had equal skill sets to do fish or meat in the same level, why not do the one that’s lacking in the market? Before I opened my shop, there was no option to get what we are selling.”

Last year, he closed Concord Fish & Prime, his store in Concord, and opened up a boutique butcher shop, M.F. Dulock Pasture-Raised Meats, on Highland Ave. in Somerville. “Our model is unique in that we only source animals within 250 miles. There’s no commodity meat here at all. What we are doing is the way things were done in the old world,” Dulock says. While the shop is tiny—700 square feet, to be exact—the advantage in the size is for the customer, who is able to have full view of Dulock and his coworkers hanging, slicing, and stuffing meats to order. Get a look at how the sausage is made here, quite literally, ahead.

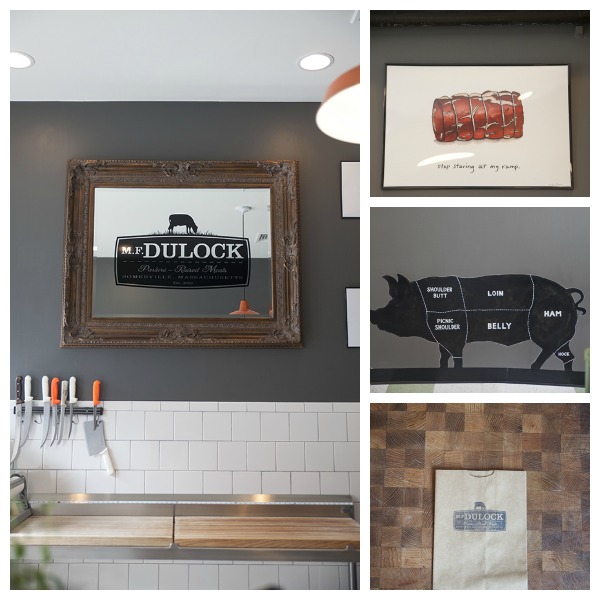

Clockwise, from left: 1. The mirror in the space comes from the home of one of Dulock’s colleagues, Maureene Gaffney, and is covered with a vinyl replication of the store logo. Dulock enlisted the help of a childhood friend, Michael Corcoran, to design the logo. “I said, ‘I want it to look like the Wells Fargo [font],” Dulock says. “I wanted the animal to be nondescript and eating grass.” 2. The space features illustrations by artist Alyson Thomas of animal cuts paired with cheeky phrases. 3. A life-sized painting of a pig (created by Gaffney) adorns the wall, as a tool for customers. “What you see is the actual size of the animals that we are cutting,” Dulock explains. 4. Bagged orders are individually stamped with the logo .

Clockwise, from left: 1. The mirror in the space comes from the home of one of Dulock’s colleagues, Maureene Gaffney, and is covered with a vinyl replication of the store logo. Dulock enlisted the help of a childhood friend, Michael Corcoran, to design the logo. “I said, ‘I want it to look like the Wells Fargo [font],” Dulock says. “I wanted the animal to be nondescript and eating grass.” 2. The space features illustrations by artist Alyson Thomas of animal cuts paired with cheeky phrases. 3. A life-sized painting of a pig (created by Gaffney) adorns the wall, as a tool for customers. “What you see is the actual size of the animals that we are cutting,” Dulock explains. 4. Bagged orders are individually stamped with the logo .

Gaffney stands with a large shelf of mason jars filled with sausage spices including bayleaf, white pepper, cayenne pepper, thyme, black peppercorns, smoked paprika, and dried parsley. Above, butcher paper and twine for wrapping up meat for customers.

Gaffney stands with a large shelf of mason jars filled with sausage spices including bayleaf, white pepper, cayenne pepper, thyme, black peppercorns, smoked paprika, and dried parsley. Above, butcher paper and twine for wrapping up meat for customers.

Above, the knives Dulock and his team rely on every day, that are always positioned on a magnetic strip within arm’s reach of the cutting table. From left: A 10-inch cimeter used for broad cuts for steaks like ribeyes or New York strips; a filet knife that used to belong to Dulock’s parents; an 8-inch fillet knife that’s technically a fish knife, but used for skinning pork belly; two 6-inch boning knives, a new set from Dulock’s knife-sharpener; a cleaver. “The knives that I use are $16 knives,” Dulock says. “For $50 in tools, you can break down any animal you want. A thousand-dollar knife won’t make you a better cutter. I understand they are perfectly balanced to your hand, but I can harness any animal I have with a cheap old plastic-handled knife.” Top right: A set of knives that have been handed down through Dulock’s family. Bottom right: A sharpening steel that once belonged to Dulock’s grandfather. “That’s probably 50 years old,” Dulock says. “I use that every day. I don’t know that my grandfather was necessarily a butcher, but some of these knives were his. Maybe people had to butcher more meat in those days.”

Above, the knives Dulock and his team rely on every day, that are always positioned on a magnetic strip within arm’s reach of the cutting table. From left: A 10-inch cimeter used for broad cuts for steaks like ribeyes or New York strips; a filet knife that used to belong to Dulock’s parents; an 8-inch fillet knife that’s technically a fish knife, but used for skinning pork belly; two 6-inch boning knives, a new set from Dulock’s knife-sharpener; a cleaver. “The knives that I use are $16 knives,” Dulock says. “For $50 in tools, you can break down any animal you want. A thousand-dollar knife won’t make you a better cutter. I understand they are perfectly balanced to your hand, but I can harness any animal I have with a cheap old plastic-handled knife.” Top right: A set of knives that have been handed down through Dulock’s family. Bottom right: A sharpening steel that once belonged to Dulock’s grandfather. “That’s probably 50 years old,” Dulock says. “I use that every day. I don’t know that my grandfather was necessarily a butcher, but some of these knives were his. Maybe people had to butcher more meat in those days.”

Dulock gets to work on a large cut of beef, which came from PT Farm and slaughterhouse in North Haverhill, New Hampshire. All of the butcher block tables in the space were crafted by Dulock himself.

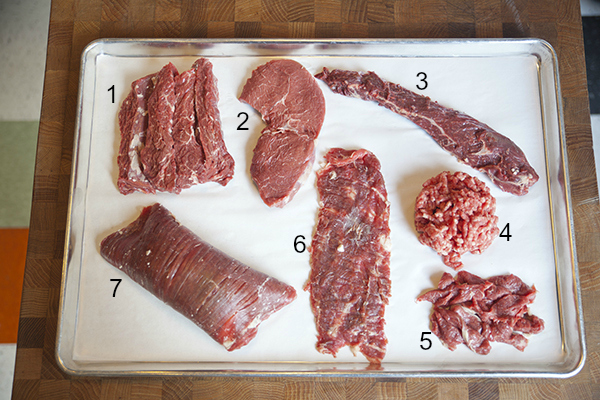

Time for a little anatomy lesson, with a subprimal cut of sirloin. 1. Tenderloin. 2. Top sirloin. 3. Top sirloin cap, also known as a Culotte steak. 4. Tri-tip steak. 5. London Broil, also known as knuckle steak or outside round.

Left: Dulock trims the excess saddle from a flank steak. Right: A large piece of sirloin flap steak. “It’s not so much a flavor difference [between the two], but a texture difference. The tighter the meat grain, the tougher the meat. We would cut [the sirloin flap] 90 degrees from the grain, and that’s your steak tips,” Dulock says.

Clockwise from top left: 1. A swivel hook, used for hanging small animals (like lamb). “It allows me to hook both achilles tendons, so that when you hang it, it doesn’t splay open,” Dulock explains. 2. Fellow butcher Jamal Coleman grinds beef for burgers. “I loosely manage, so we are all bosses,” Dulock says. “Everybody here that works for me is capable of doing any job.” 3. A bandsaw is used for breaking down large, bone-in cuts of meat. “When you cut by hand, there’s a variance in the angle of the chop or bone you are cutting because the blade tends to wander a little bit. In a bandsaw setting, because the rotation is so fast, you slice right through like you are cutting through bread.”

The bandsaw in action, separating a sirloin cut (left) from a short loin cut (right).

Top: A cleaned-up short loin. “The face of that cut on the larger side is the Porterhouse,” Dulock says. The circular muscle on the right is the filet mignon, which tapers through the short loin at which point the cut becomes a T-Bone instead of a Porterhouse. Bottom left: A large hunk of filet. Bottom right: Burger mix goes through the grinder. “It’s generally 80/20,” Dulock says. “We make everything in the case look really pretty and nice. Anything that gets cut up at an odd angle or that doesn’t look nice goes into the grinder,” Dulock says. “The majority is chuck and chuck round, because that has the most volume and gives a really good, all-purpose ground beef.”

Broken-down beef cuts sit on the counter.

Anatomy lesson, part two: 1. Sirloin tips. “That’s a pretty versatile cut because it’s a tender muscle and cooks quickly. That’s the same for every cut on this tray—they are all designed to be cooked very quickly.” 2. Top sirloin. 3. Hanger steak 4. Ground beef. 5. Sirloin that’s been cut for stir-fries. 6. Skirt steak. 7. Flank steak.

Dulock has amassed such a large collection of volumes devoted to meat at his home, that he’s let some spillover fill the shelves in his shop.

Dulock has amassed such a large collection of volumes devoted to meat at his home, that he’s let some spillover fill the shelves in his shop.

Left: Top to bottom, broken-down pork parts. 1. Bone-in loin chops. 2. Leaf lard. “That’s from inside the carcass, it covers the kidney and the inside of the organ cavity,” Dulock says. “That you can render down, and it’s a flavorless lipid that you can use for pie crust.” 3. Pork “sirloin.” “With pigs we don’t isolate the muscles the same way that we do with beef, but they are all there,” Dulock says. 4. More leaf lard. 5. A slab of pork belly. 6. Pork ribs. 7. A cross-section of a ham. 8. Back fat (more commonly referred to as “fatback”) for making sausage. “When we are making sausage, the amount of fat used is more important than with ground beef. The fat is weighed.” 9. In front of the metal bin is a pork femur. Inside are pork scraps used for sausage grind. Top right: Bay leaves, mustard seeds, and chili flakes, all essential components in sausage seasoning. Bottom right: From left, Mexican-style chorizo, Toulouse sausage (French country-style, with garlic, parsley, and wine), and sweet Italian sausage.

Left: Top to bottom, broken-down pork parts. 1. Bone-in loin chops. 2. Leaf lard. “That’s from inside the carcass, it covers the kidney and the inside of the organ cavity,” Dulock says. “That you can render down, and it’s a flavorless lipid that you can use for pie crust.” 3. Pork “sirloin.” “With pigs we don’t isolate the muscles the same way that we do with beef, but they are all there,” Dulock says. 4. More leaf lard. 5. A slab of pork belly. 6. Pork ribs. 7. A cross-section of a ham. 8. Back fat (more commonly referred to as “fatback”) for making sausage. “When we are making sausage, the amount of fat used is more important than with ground beef. The fat is weighed.” 9. In front of the metal bin is a pork femur. Inside are pork scraps used for sausage grind. Top right: Bay leaves, mustard seeds, and chili flakes, all essential components in sausage seasoning. Bottom right: From left, Mexican-style chorizo, Toulouse sausage (French country-style, with garlic, parsley, and wine), and sweet Italian sausage.

True story: the sausage filler is emblazoned with the word “Dick.” But it’s not from a wicked sense of humor—it’s crafted by the German butcher tool manufacturer F. Dick. “I know it’s giggly—you don’t get rid of that,” Dulock says. “That’s the ‘little dick,’ it’s only a 12-pound stuffer. There’s’s also a ‘big dick,’ a 30-pound sausage stuffer. That thing is our godsend, it saves us so much time. We blend [the mixture] by hand, then we fill up that cylindrical chamber. Then the meat is forced through the tube into the sausage casing. You aren’t re-grinding or emulsifying the sausage, which allows you to have a [coarser] texture that’s unlike that of a hot dog.” On weekends, Dulock typically stocks 6-7 types of sausages, with 2-3 available during the week.

True story: the sausage filler is emblazoned with the word “Dick.” But it’s not from a wicked sense of humor—it’s crafted by the German butcher tool manufacturer F. Dick. “I know it’s giggly—you don’t get rid of that,” Dulock says. “That’s the ‘little dick,’ it’s only a 12-pound stuffer. There’s’s also a ‘big dick,’ a 30-pound sausage stuffer. That thing is our godsend, it saves us so much time. We blend [the mixture] by hand, then we fill up that cylindrical chamber. Then the meat is forced through the tube into the sausage casing. You aren’t re-grinding or emulsifying the sausage, which allows you to have a [coarser] texture that’s unlike that of a hot dog.” On weekends, Dulock typically stocks 6-7 types of sausages, with 2-3 available during the week.

All sausage recipes are meticulously cataloged in a Japanese notebook that Dulock purchased in San Francisco. Pictured, the recipe for beef kofte kebabs. “The first column is the master recipe. The next two columns are for the 2x recipe and the 4x recipe,” Dulock says.

“Since we don’t have cranes or hoists, we have to do everything by hand so we have the beef arrive in 8ths instead of in quarters,” Dulock says.

“Since we don’t have cranes or hoists, we have to do everything by hand so we have the beef arrive in 8ths instead of in quarters,” Dulock says.

Left: After the beef comes in from the farmer or slaughterhouse, “we will hang the whole carcass on the rails, and let it age for 7 days,” Dulock explains. Then, the beef is broken down into primal cuts and aged further. “The age of meats in the case is 14-21 days. That’s true dry-aging. Even our ground beef is dry-aged ground beef,” Dulock says. Right: Curls of pork skin, ideal for making chicharones. To create the shape, Gaffney wraps wet pieces of skin around a chopstick, and allows it to dry.

Left: After the beef comes in from the farmer or slaughterhouse, “we will hang the whole carcass on the rails, and let it age for 7 days,” Dulock explains. Then, the beef is broken down into primal cuts and aged further. “The age of meats in the case is 14-21 days. That’s true dry-aging. Even our ground beef is dry-aged ground beef,” Dulock says. Right: Curls of pork skin, ideal for making chicharones. To create the shape, Gaffney wraps wet pieces of skin around a chopstick, and allows it to dry.

The finished product of Dulock and his staff’s hard, diligent work: a meticulous, gorgeous meat case.