How Fermentation Is Used At No. 9 Park

Welcome to Chefology, where married couple Ben Wolfe (a Harvard microbiologist) and Scott Jones (the chef de cuisine at No. 9 Park) explore the relationship between biology and haute cuisine. This is, quite literally, a marriage of science and cooking.

Welcome to the first installment of Chefology—but before we get started, here’s a little background on us. Ben is a Harvard PhD. He studies the microbes that give delicious flavors to cheese and other fermented foods. He is courted by cheese makers, salami producers, chefs, and hobbyists to understand the burgeoning world of fermented foods. Over the last two years, he has worked closely with Jasper Hill Farms in Vermont to understand the science and biology behind the development of their cheese.

Scott, meanwhile, works at No. 9 Park. He quit graduate school (he studied cancer biology at Harvard) to knock on doors of area restaurants, but he only wanted to work at one. A year after our engagement dinner at No. 9 Park, he started there as a line cook, picking greens, and sweeping the floor during service. Today he is the chef de cuisine, writing the menus, hiring the staff, and training those who show the same drive he did four years ago.

As our career paths have diverged, we’ve learned a lot about the similarities and differences between the lives of a scientist and a chef. In this blog, we’ll reflect on the exciting interplay between science and cooking as we experience it from day-to-day. First up? Let’s talk about fermentation.

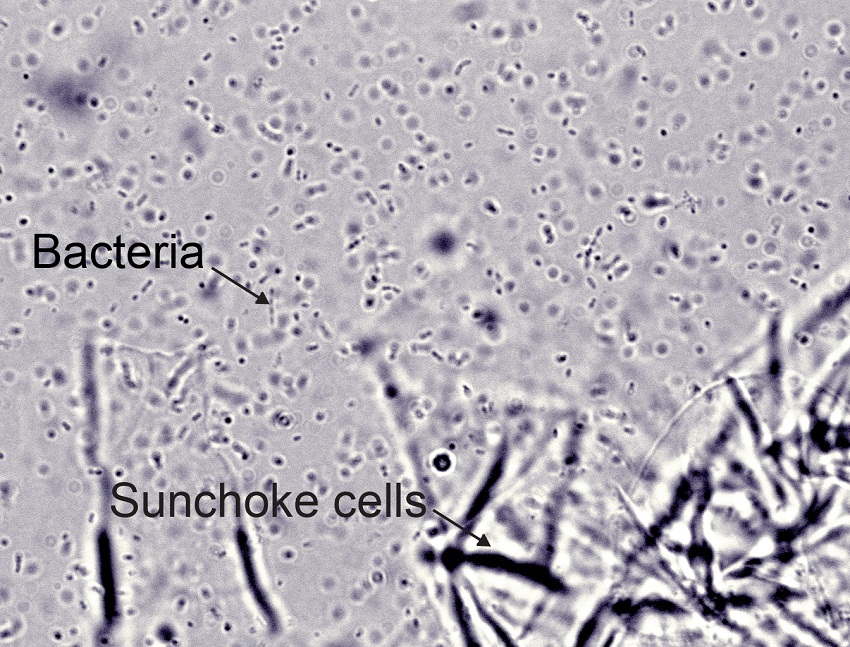

Fermented sunchokes (bottom left) are used as ingredients No. 9 Park.

Rotting food. In the restaurant industry, it’s a red flag for health inspectors and a great way to lose profit. But in kitchens of some of the finest restaurants in the world, rotting food has become a symbol of culinary innovation. As the Sandor Katz fermentation revival has swept across the food world, savvy diners are being drawn to menus featuring ingredients that are cured, pickled, and aged.

In the simplest terms, fermentation is controlled rot. Microbes (bacteria and fungi) eat sugars in the raw ingredients and produce wastes or byproducts that are useful and delicious to us. Lactic fermentations, where bacteria eat the sugars and produce lactic acid, are what give us fermented dairy products like cheese and fermented vegetables like sauerkraut. Alcoholic fermentations give us booze. And acetic fermentations give us various forms of acetic acid, commonly known as vinegar.

Sauerkraut and yogurt are lovely, but how can we incorporate fermentation into fine dining to satisfy the continuous quest for new flavors and ingredients? Here are two dishes that we worked on together for the menu at No. 9 Park using Ben’s knowledge of the microbiology and Scott’s knowledge of crafting a fine dining tasting menu.

Fermented sunchokes

At No. 9 Park, Scott ferments Jerusalem artichokes, or sunchokes, that he buys from Eva’s Garden. When fresh, sunchokes have an earthy, nutty, and vegetal flavor. These starchy tubers are sometimes called called a “fartichoke” because of their ability to cause gas when eaten raw. Your body can’t digest the compound inulin that is abundant in these root vegetables, but the beneficial bacteria in your gut can. When those bacteria in your colon get busy, they produce a lot of flatulence.

One way to add some zip to the sunchokes and to cut back on the farts is to ferment them. Encouraging the growth of lactic acid bacteria (the same “probiotic” bacteria that are the live cultures in your yogurt) during the fermentation process causes the breakdown of the sunchoke to happen outside of your intestine, allowing it to have a more gentle trek through your digestive system.

The microscopic line cooks of No. 9 Park. This image shows a piece of a fermented sunchoke magnified 1000 times. The lactic acid bacteria that ferment sunchokes can be seen as tiny round specs. Each spec (~1 µm in length) is a bacterial cell. Billions of bacterial cells ferment each sunchoke.

Fermented sunchokes have a slightly acidic twang, with a sweet and sour accent. Their sweet-salty-sour flavor pairs wonderfully with fish. Scott currently has a halibut dish on the prix-fixe menu that starts with a green garlic and preserved lemon puree, and the halibut sits on a ragout of rock shrimp, fresno chile, and the fermented sunchokes.

To ferment sunchokes, Scott peels, grates and rinses the sunchokes several times to remove any dirt or discoloration. They are then put into a 5% brine (for 1 liter of water, add 50 g of salt). This concentration of salt stops bad bacteria from growing and allows for the lactic acid bacteria to thrive. You don’t need to add these bacteria – they are already abundant on the outside of the sunchoke roots. Be sure everything is completely submerged in the brine by placing plastic wrap on the top of the brine and leave it at 55-65 º F for three days. If you want more lactic zing, let the artichokes ferment for another day or two.

Kombucha-marinated turbot

Kombucha is a really ugly fermentation, even to a microbe-loving food microbiologist. Even most meticulously prepared kombucha will have a slimy, stringy mass floating on the surface of some tea. This mass is known as a mother and consists of billions of yeast and bacterial cells. To make kombucha, you add a mother to tea with significant amounts of sugar. The yeast use the sugar in the tea to make alcohol and the bacteria eat up the alcohol and produce acetic acid (vinegar). Despite the ugliness, the funky-boozy-vinegar flavors from this fermented tea are strangely intoxicating.

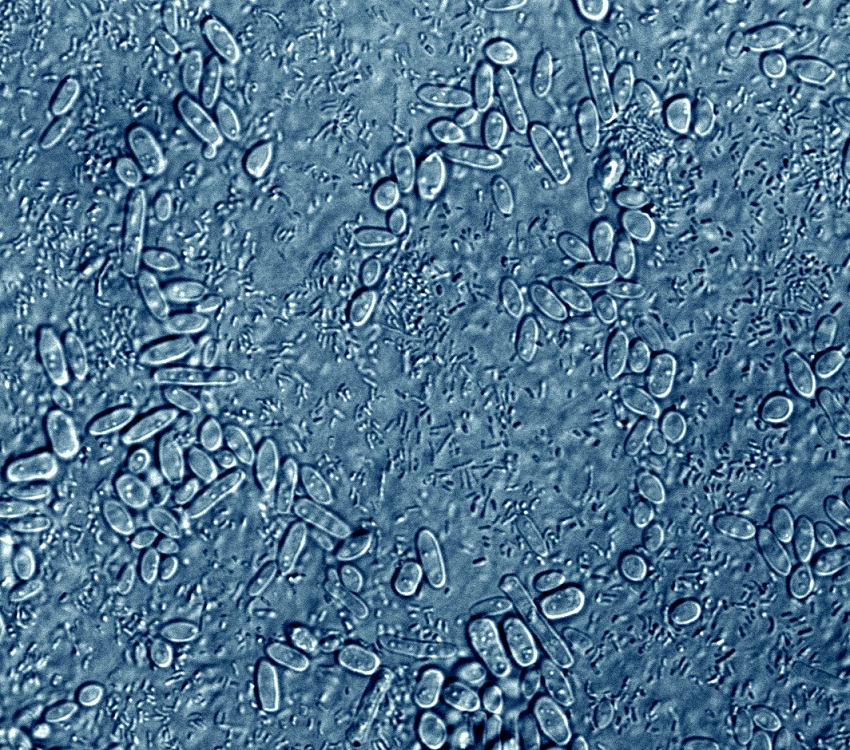

A microscopic view of yeasts (large ovals) and bacteria (small ovals) that live in a kombucha mother.

Ben was experimenting at home with making his own unsightly (but delicious!) kombucha. When we dared to try it, it tasted sweet, sour, and kept some of the bitter flavors of tea. Similar to the sunchokes, this made Ben think of fish, and say to Scott, “You should use kombucha on the menu. Maybe marinate some fish with it.” And as one learns in marriage, this is not a suggestion, but a requirement. “Yes, chef,” was the response.

Kombucha-marinated turbot with black garlic, pickled watermelon cucumbers, and watermelon radishes.

Scott picked turbot, a fish with a firm texture and higher fat content, to stand up to the kombucha. Turbot was sliced thin, marinated in kombucha, and then dressed with warm oil seasoned with garlic, chili threads, and lime zest, as a form of escabeche. It was paired with black garlic (a fermented garlic), pickled watermelon cucumbers (also fermented), and watermelon radishes (which are not fermented, but taste funky). The funk of the kombucha carried through the dish and added a depth of flavor that vinegar or tea alone wouldn’t achieve.