The Trailblazer

Steve Herrell: I introduced a style of ice cream based on a low overrun, or the amount of air in the ice cream. The home-style ice cream freezer, which is the one I used at Steve’s, incorporates much less air into the ice cream while freezing.

Gus Rancatore: Steve made the ice cream in front of people in an old-fashioned White Mountain Equipment Company ice and salt machine. Steve, and Steve’s Ice Cream, set the clock back to pre-industrial food preparation. And I think Steve is related to microbreweries, the back-to-the-farm mentality, all of those things.

Marc Cooper: I was one of the early customers. There’d be lines, no matter what time of day—I’ve waited two hours there. It was an event.

G.R.: We quickly became the busiest ice cream store in the area. Steve used to go to the HP Hood Factory, in Charlestown, to pick up milk and cream in his VW Bug. One day he was buying so much of it that the guy in charge of ice cream operations for HP Hood came down and said to Steve, “You know, we will deliver this if you want.”

S.H.: It was a place with character. I put in the dropped ceiling myself, and I bought used chairs and tables—they were mismatched, but I painted them purple and orange. My goal was not to produce ice cream that was the least expensive and the most profitable. My goal was to make the best ice cream possible.

G.R. Steve was very eccentric, kind of a hippie guy. He didn’t have a very nice car, he didn’t dress expensively. Even when he could have made a lot of money, he always refrained from it.

S.H.: The concept was to take name-brand candies and mix them into the ice cream. That was new. Of course, you could get chocolate chip or maple walnut before Steve’s, but Heath Bar Crunch and cookies and cream came right out of Steve’s Ice Cream.

M.C.: He had bananas stacked on top of one area—he used every inch of space in the store. Before reaching the counter, there’d be a sign that said, “This is how you order.” To speed up the process, you’d pick a flavor, and something you’d want mixed in.

G.R.: Steve’s was very important in catalyzing a change in Davis Square. Somerville was this incredibly pugnacious, blue-collar suburb. Steve’s changed Somerville the way that Olives changed Charlestown and Hamersley’s Bistro changed the South End.

One Good Cone Deserves Another

The opening of Steve’s ignited a decade-long ice cream boomlet in Boston.

1973

Steve Herrell opens Steve’s, in Davis Square.

1975

The lawyers Robert Rook and Richard Rubino launch Emack and Bolio’s, in Coolidge Corner—a shop named for two of their homeless pro-bono clients.

1977

Herrell sells Steve’s to Joey Crugnale, the founder of Bertucci’s, and moves to western Massachusetts.

1980

Herrell makes his Boston-area comeback with the franchised chain Herrell’s.

1981

Gus Rancatore says goodbye to Steve’s and, with his brother Joe, opens Toscanini’s, in Central Square.

1981

Vincent Petryk opens the first J. P. Licks, in Jamaica Plain, of course.

1984

Petryk sells his J. P. Licks location in Inman Square to a former employee, Steve Cirame, who names it Christina’s, after his daughter. (Ray Ford, its current owner, later bought out Cirame in 1993.)

1984

Marc Cooper, a big Steve’s fan, quits his job as a radiology production manager at Mass General to open a Herrell’s franchise in Allston.

1985

Joe Rancatore leaves Toscanini’s to open Rancatore’s, in Belmont.

Photograph by Scott M. Lacey

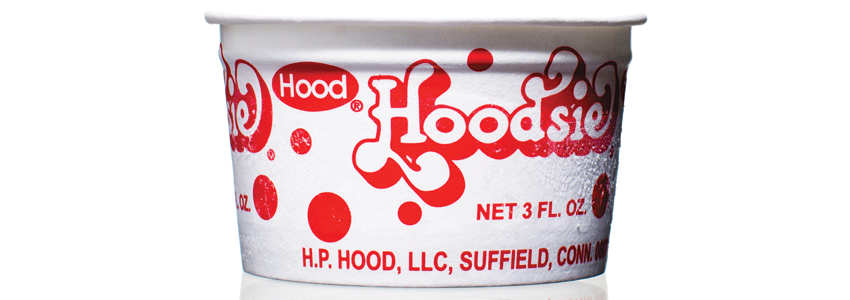

Cup of Excellence

The Hoodsie—with its unique combination of vanilla-chocolate ice cream, printed waxed paper cups, and wooden “spoon”—is synonymous with childhood in New England. Newton native Michael Leviton, the chef-owner of Area Four and Lumière, likes Hoodsies so much that he’ll be serving them straight from the bag at A4, a new Area Four outpost coming soon to Somerville. Serving them, that is, until he perfects his own recipe and offers from-scratch versions. With the Hoodsie, he says, “it’s all about mouth-feel and having this very light-textured stuff that doesn’t melt on a summery day.”

Want more?

Check out our complete summer ice cream package.