Chefology: The Science of Sherry

If your grandma’s sweet nightcap is the first thing that comes to mind when you see sherry on a wine list, think again. While sherry remains one of the world’s most poorly understood wines, the science and art of sherry production are perhaps some of the most fascinating among fine wines. Here, an introductory primer on sherry production and how it pairs with food.

What is sherry? A most basic definition is a fortified wine produced in the Sherry-Jerez-Xeres region of southwest Spain. There are three towns that make up the “sherry triangle,” and all sherry in the world is produced in this small area. Almost all sherry is made from the palomino grape which grows in that region, though sweeter sherries are made from moscatel and Pedro Ximenez.

The first steps of sherry production are fairly standard wine production: grapes are fermented with a yeast to transform sugars into alcohol. After fermentation, sherry is fortified by adding a high alcohol grape distillate (aka, brandy) leading to 15-22 percent alcohol content. After fortification, aging and blending takes place in a bodega where the wine is aged in oak casks (called butts). It’s during this aging phase where the magic happens, leading to the surprising diversity in sherry wines.

The surprising diversity of sherry wines, from light and dry fino and manzanilla (glasses on the left)

to dark and sweet oloroso (glasses on the right). / Photo by Melodie Reynolds

One way to create diversity in sherries is through the use of a natural layer of yeasts that forms on the surface of the aging sherry. This slimy mat of microbes, called a flor, contains yeasts that prevent the wine from coming in contact with the air and oxidizing. The yeasts of the flor also consume the residual sugars present in the wine, which leads to reduced sweetness and the development of a range of flavors. If the flor is maintained throughout the aging process and little to no oxidation takes place (called biological aging), the wine produced is called a fino or manzanilla. Variation in the strains of yeasts in the flor among different wineries leads to variation in flavors. Aged manzanilla can only be produced in the seaside town of Sanlucar de Barrameda; fino comes from the other two towns, Jerez, and El Peurto de Santa Maria. These wines are clear, delicate, and bone-dry. They are best served chilled and make for an incredible aperitif.

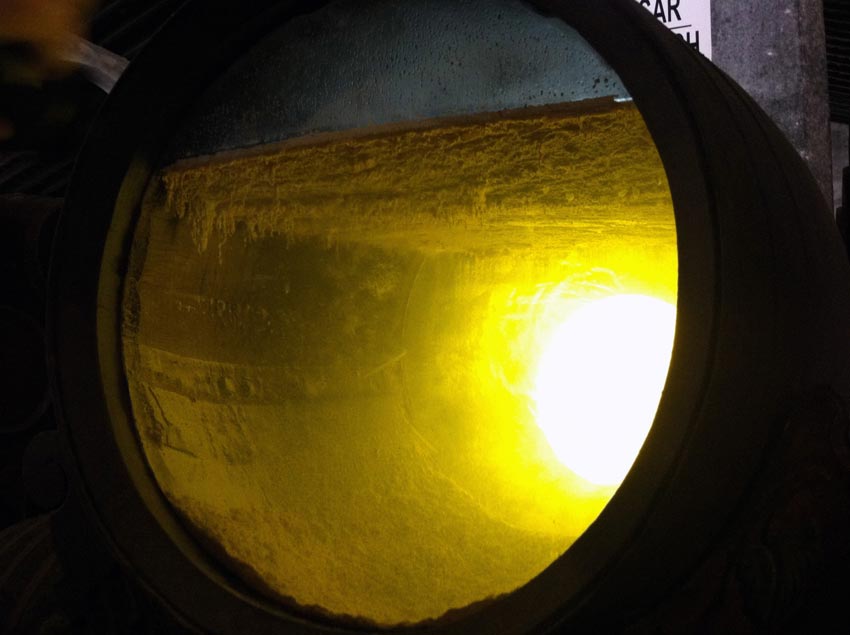

A cross-section through a barrel of aging sherry where a flor has grown. The sherry fills roughly 80% of the barrel and has an

undulating layer of yeasts floating on the surface. This layer is called the flor. / Photo by Scott Jones.

Another source of diversity in sherry comes from the blending of old and new batches. Sherry aging uses a solera system, where barrels are stacked on top of each other. The oldest wine is at the bottom (or solera), and several times a year, wine from one layer (or criadera) is partially blended with the layer of barrels below. Wine is removed from the bottom row for bottling and the wine removed is replaced from the layer above, which is replaced from the layer above that, and so forth. The top layer is restocked with the new wine from that year’s harvest. The bottom layer contains some wine that is as old as when the solera began, in some cases older than 50 years. Because of all of the blending, sherry has no vintage.

Sherry is aged using a solera system, where new wine is put in top barrels and older wine is in lower layers of barrels. Blending between ages of wines leads to diversity in flavors. / Photo by Scott Jones.

If the alcohol content is too high or the wine isn’t blended often enough to provide new sugars to feed the flor, the flor will die. When the flor dies, oxidation takes place, darkening the wine, and developing a range of nutty and caramelized tones. If a wine lives most of its life as a fino and is only oxidatively aged toward the end, it produces an amontillado. These wines are the lightest and driest of the oxidated sherries. More oxidation leads to a darker, richer, more full-bodied wine, called oloroso. Those sweeter sherries you may have seen before come from mixing the ultra-sweet Pedro Ximenez sherry with oloroso, creating what’s known as cream sherry. Pedro Ximenez never ages under flor, meaning the residual sugars left after the initial fermentation are left to concentrate.

Sherry has an impressive versatility in food pairings. In collaboration with the wine manager of No. 9 Park, Melodie Reynolds, Scott recently explored the pairing of sherry with diverse foods as a contestant in the 5th Copa Jerez. Chefs and sommeliers from restaurants around the world wrote a three-course menu that paired sherry with each course. Judges evaluated the match of sherry and food, the quality of the food, and the explanation by the team of why they paired that food and sherry. After winning the U.S. competition in New York in July, Melodie and Scott went on to Spain in early October for the world competition, where they won Most Overall Creative Menu and Pairings.

Here’s their menu and an explanation on how the sherry was paired with the food:

Artichokes en barigoule, oyster veloute, smoked deviled quail eggs, white sturgeon caviar, manzanilla olive and orange relish.

Hidalgo la Gitana Manzanilla

The wine is delicate, though complex, with flavors that call out to the orange and the smoke. Manzanilla, aged by the sea, can have a strong salinity, which pairs well with the caviar, oysters, and olives. Since the wine is so dry, we liked the texture of the creamy eggs and veloute paired with the crisp wine.

Rohan duck breast, seared foie gras, marcona almond puree, fried brioche, fennel pollen, white asparagus and truffle marmalade, huckleberry and leek ash jus.

Lustau Almacenista “Pata de Gallina” Oloroso

This wine is dry, but funky and rich, and pairs well with the rich umami flavors of duck and foie. The bitterness of the jus highlights the sweetness of the wine. This pairing was about matching complexities.

Mango mousse, chestnut honey and rooibos tea puree, graham cracker financier, rooibos tea glace, fried chestnuts.

Cesar Florido Moscatel Especial Chipiona

This was the easiest pairing, perhaps. When you smell this wine you think of tropical fruits. It has a high floral tone that calls to the rooibos tea and aromatics in the chestnut honey, but also darker notes to pair with the graham spices and fried chestnuts.

If you’re new to the realm of sherry, try tasting through several: start with lighter, delicate manzanilla and fino, dip into amontillado, keep going with oloroso, and finish with a drop of Pedro Ximenez. Eat food with sherry. And try a sherry when you might normally drink another type of wine. A good rule of thumb? When you might drink chablis with oysters, try fino. When you might drink pinot with duck, try oloroso.