Chefology: The Five Tenets of Pairing Food With Science

In cooking and in science, finding connections between ingredients and data points is a common goal. In science, there is a somewhat rational basis for finding those connections: the scientific method. Ask a question, design an experiment, generate data, and revisit your question to see how the data fit your original hypotheses.

Is there a similar scientific method to putting together a dish or tasting menu in fine dining? Yes and no.

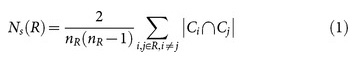

Scientists have attempted to quantify and identify the methodology of food pairings. In 2011, a team from Northeastern University and Harvard attempted to show that there’s a different approach to food pairings in different cultures. In the journal Nature, they suggested that Western cultures pair foods that share flavor compounds, and Eastern cultures avoid pairing ingredients that overlap. The authors tried to come up with an equation that could describe this property of food pairings:

So, does this mean that when Ben asks Scott, “Why did you use those ingredients together?” Scott simply jots down a few equations, shows them to Ben, and the question is considered answered?

Not so much.

Despite the scientific interest in trying to find underlying principles behind food pairings, the process of putting together a dish or menu is, in actuality, based on experience and history. Novelty in food pairing comes from experimentation, understanding how flavors balance one another, and a great deal of reading. Here are a few approaches commonly used in fine dining to construct a dish.

1. Things that Grow Together, Go Together

This is a common saying in food pairings, and in wine pairings, too. This speaks to seasonality and location. Before food globalization and mass marketing, cooks were limited to what was available in one place and one time. Stand in your garden at the peak of the summer harvest, and you can see a beautiful ratatouille around you—tomatoes, eggplant, bell peppers, zucchini, basil, marjoram, all in season and ready to harvest in the same garden plot. Pair it with a rose from Bandol and you’re eating a place and time. Few approaches offer such success.

2. Building a Narrative

Some of the best dishes come from creating a story. We like to think that we taste food in a vacuum, but we really love the context. At No. 9 Park, Scott once offered a dish that featured grass-fed beef from a local farm, poached in whey made from the same cow’s milk, and then served with ricotta made from that same milk. He then added a chickpea farinata, a pancake that is a traditional Ligurian street food, and a broccoli rabe pesto (also traditional from Liguria), and you could see a whole history in one dish. Nearby in Piedmont, truffles often grow on the roots of hazelnut trees, prompting Scott to use one of his favorite pairings. Describing that these foods go together in part because they live symbiotically in Northern Italy offers a powerful narrative.

3. Biology Informs Flavors

The more we learn about flavor chemicals, the more we can experiment with flavor pairings. In a previous post, we wrote about furanones, the compound that is similar to both tomatoes and strawberries. Scott used that information to create a strawberry flavored pasta (which tasted like a tomato flavored pasta), and paired it with a calaminth pesto (calaminth is like a cross between oregano and mint). The result was a dish based on tomato and oregano, which became strawberry and mint.

4. Nothing Beats Experience

In a recent interview, Scott was asked, “What is the most important thing when you’re creating a dish?” His answer: Hunger. You have to be hungry. Hunger stimulates the mind to think of all the dishes you’ve eaten and want to eat now. When you are hungry, you can practically taste what you want to eat. Ideas come to you that wouldn’t when you’re full. Lobster and chamomile sound like a strange pairing, but every time he uses it, Scott falls in love with it more. Duck confit and shrimp remind us of a late night trip to Chinatown. Medjool dates and tuna crudo is tough pairing to explain, but was a hit with guests at No. 9 this past summer.

5. Balance Is Important

Acidity, bitterness, spice, savory, sweet, salt. A good dish hits every note in the right way. Sometimes all it needs is a little lemon juice.

For the best reading on flavor combinations, we highly recommend Niki Segnit’s The Flavor Thesaurus. Her writing is clear, precise, funny, charming, and inspiring. We cannot recommend it enough.

And sometimes, the best way to learn about new food pairings is to talk to new people. So, what strategies do you use to pair foods? Any favorite pairings you wish you saw more of? Let us know in the comments.