Growlers in Massachusetts: A War on Glass

Tim Oxton / Night Shift Brewing

Night Shift Brewing is everywhere. Since opening in 2012, the brand has spread like wildfire into Massachusetts liquor stores and bars. Lucky for us, that ubiquity means it’s easier than ever to imbibe in the Everett company’s beer, whether it comes from a can, bottle, or tap line.

If you visited the brewery’s taproom over the past few years, you might have noticed another way to bring beer home: growlers. These bulbous glass jugs are filled to order with draft beer for later drinking. After being purchased for an initial fee or deposit, the vessel can then be brought back for subsequent fills.

On paper, it’s an environmentally conscious, waste-free way to enjoy a drink at home—grab a growler, polish it off, then bring it back for a refill. But you won’t find growlers at Night Shift anymore. Due to a slew of state regulations and quality issues surrounding the use of growlers, the company scrapped glass jugs from the business plan last year, and they’re not the only local brewery that is moving away from growlers.

“Our mission is to brew world-class beer and have people enjoy it in its peak condition. Growlers don’t help us get to that mission,” says Rob Burns, cofounder of Night Shift and president of the Massachusetts Brewers Guild. “I know some other brewers that have already eliminated growlers for many of the same reasons.”

The Drinker’s Plight

By law, Massachusetts breweries can only sell and fill growlers that display their own branding on the front (or are entirely blank—more on that in a bit). This restriction stems from federal labeling guidelines and legal language interpreted by the Massachusetts Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission (ABCC). The state doesn’t actually have any laws that specifically address growlers, so the ABCC defers to federal guidelines to define what drinkers and breweries can do.

Per these rules, a growler from Trillium Brewing Company cannot legally be filled anywhere in Massachusetts, other than Trillium. Likewise, you can’t tromp over to Winter Hill Brewing Company in Somerville and expect them to fill a growler from Harpoon Brewery. They can’t, and they won’t.

From a consumer standpoint, it’s easy to spot the draconian issues with this system. Drinkers can amass upwards of 15 to 30 different growlers that, more often than not, collect dust on shelves. And remembering to bring a growler to its associated taproom requires an additional layer of planning. Growlers are a useful tool for drinkers who frequent the same business, or live in close proximity to a brewery, but most consumers would argue for the freedom to simply fill their growlers anywhere, rather than be limited to a single place.

In May, the ABCC elaborated on guidelines for unmarked or blank growlers, stating that growlers from elsewhere could be filled anywhere, as long as they’re “entirely blank” and “devoid of any labeling of another brewery.” No legislation was added or altered; it was simply a clarification. Since the statement says these changes are in response to “several inquiries,” it implies that the ABCC is aware of the pushback on state growler usage.

A step in the right direction, maybe, but this hardly adds much to the discussion. Also, who owns a blank growler?

These tweaks don’t specify any particular size or material of the growler, either, which is cause for more confusion. Plus, this announcement blindsided local brewers, and now many are scrambling to update their filling policies. While drinkers are more eager than ever to snag a blank jug and head to their favorite spot, some establishments, like Trillium, aren’t changing their rules until they can sit down and hash out a game plan.

Staying Power

Despite the update, labeled growlers are still sold at most Massachusetts breweries. When growlers first came about in the 1800s, it made more sense to use them. At that time, the vessels were more like buckets that held beer. The name was adopted from the bellowing, growling sound the liquid made when it splashed around in transit. When the container evolved into a glass jug, it was still the simplest and most efficient solution to transporting beer at the time.

“Some of the early appeal was that draft beer was not pasteurized and packaged beer was, so it tasted even better from the taps than the bottle,” Burns says. “[Growlers] also easily allow consumers to pick up smaller batch, one-off beers that don’t get packaged in cans or bottles.”

Technology made strides, though, and growlers had to compete with cans and bottles. While Burns’ point about small-batch draft beers is still true in some cases, many breweries like Night Shift don’t pasteurize or filter their beer at all anymore, so it’s the same in a can as it would be in a growler. And, because most growlers are filled right from a tap, the beer inside is actually more susceptible to going bad than a beer in a carbonated container.

Growler laws never really caught up with the craft beer boom, it seems. That’s not a unique issue in Massachusetts, which has touted plenty of strange and archaic laws regarding alcohol. Some stances, especially the taboo of hosting a formal happy hour, are just laughable against the state’s other left-leaning freedoms.

The powers that be seem to have realized the irony. Early this year, treasurer Deborah Goldberg convened an Alcohol Task Force that will review regulations and restrictions surrounding alcohol, such as when it can be sold and what IDs are acceptable to purchase it. Among the most requested changes from consumers, per the Boston Globe? Easing growler restrictions.

But whether new laws are made to grant growler filling freedoms or not, the vessels are here to stay for now. The majority of the 120-plus breweries in Massachusetts sell growlers as a means to take beer home. Around two-thirds of breweries in Boston alone currently offer growlers. And interestingly enough, some of the state’s brewers would prefer to leave these laws the way they are. For them, growler laws are a safeguard for maintaining the quality of beer that leaves their taprooms. Those brewers want to avoid consumer confusion, and simultaneously defend their branding.

“Our brand is one of the most valuable assets we have, or any brewery has, and we will protect it to the greatest extent possible,” writes Brian Shurtleff, cofounder of Bog Iron Brewing in Norton, in a blog post on the subject.

For concerned brewers like Shurtleff, lenient growler filling rules could threaten the branding they have spent years building. If a customer drinks beer they don’t like out of an misbranded growler, that stigma could be associated with the wrong business. That idea has left some local brewers wary of, if not opposed to, changing the status quo. This is also the ABCC’s reason for keeping regulations as it is.

At the moment, growler reform is not on the floor of the House or Senate for review. There have been attempts to change this in the past few years, though. In 2015, an amendment was brought forward by Rep. Steven Howitt of Seekonk (R-4th Bristol) to let consumers fill growlers at any brewery, but the bill eventually died on the floor. Howitt has has tried again since, according to the Boston Business Journal, to no avail.

If and when a new law goes into effect, some local brewers want the option to opt out of any amended legislation, according to the nonprofit Massachusetts Brewers Guild that represents the state’s brewers and their interests. So, until compromise can be achieved on all fronts, some local brewers are just avoiding growlers all together.

Bone Up growler signage and 32-ounce branded jugs. / Photos provided by Bone Up Brewing

Fitting the Bill

Not every brewery has the luxury of simply ignoring growlers. For newer businesses like Bone Up Brewing Company in Everett—blocks away from Night Shift—growlers are a means to get their foot in the door. The owners sell beer to-go exclusively in growlers, since they don’t currently have the resources to invest in alternatives.

“We launched with growlers because we basically had to,” says Liz Kiraly, who opened Bone Up with her husband, Jared, in August 2016. “There’s no room [in our brewery] for a bottling or canning line. Bottling by hand is super labor-intensive; some small breweries do it, but that just wasn’t an option for us.”

Bone Up needs time to build its business before introducing other means of distribution, Kiraly says. Growlers offer a low buy-in, which attracts budding businesses. To invest in a canning line, or use a mobile canning service, a brewery needs the space and a high production volume. Kiraly notes that cans normally need to be purchased in large quantities, too much for Bone Up’s three-barrel production system.

The Kiralys say they are in favor of amending current legislation and would willingly fill growlers from elsewhere. The two also hope to introduce another form of packaging this summer to coexist with growlers. But they aren’t in a hurry to ditch the glass containers. Growlers require consumers to come to the brewery’s taproom and experience the space firsthand. That’s a huge plus for the Kiralys.

“We want to focus on being a neighborhood taproom and make beer for our zip code,” Kiraly says. “We want people to come to us. We want to meet them and enjoy talking with them about beer, so we put our efforts into creating a space and taproom, rather than focusing on distribution and spreading our product far.”

State growler restrictions can also manifest in odd ways: Springdale Barrel Room opened in December 2016 on the same Framingham block as its sister brewery, Jack’s Abby Craft Lagers. Since both brands are under the same ownership, drinkers can legally fill Jack’s Abby-branded growlers at Springdale, and vice versa. To perhaps embrace this exception, both companies plan to eventually sell co-branded growlers.

Searching for Solutions

While Massachusetts drinkers might find it normal to drink under these odd regulations, the rules vary by state. Over the past several years, states such as New York and Connecticut have begun to relax their laws and interpretations.

While you still have to buy a growler for an initial fee in these places, businesses can fill clean containers from elsewhere without issue. According to William Goggins, a licensing director with Vermont’s Department of Liquor Control, his state’s laws were amended about five years ago to omit the world “growler,” since people began coming up with other things to put beer in. Vessels ranged from Capri Sun-like mylar bags, to stainless steel monstrosities. Now, “container” is the new umbrella term to define any vessel in the Green Mountain State.

More lax laws in nearby jurisdictions have some Massachusetts residents packing up their growlers and crossing state lines, but there’s no guarantee they will return home with beer. While growler restrictions in Vermont allow for more freedom, there’s nothing stopping a brewery from refusing to fill a growler that isn’t its own, simply because it doesn’t want to.

To address any confusion about what’s in the growler, Vermont breweries will use a sticker, or extraneous tag on the bottle, to identify what’s inside. When the consumer fills that growler with something else, another sticker or tag is applied accordingly. These practices have even paved the way for a new business model—growler filling stations inside some package stores and bars.

Stickers could be a plausible solution to brewers’ worries, but Massachusetts legislation would still need to be instituted to recognize the practice. Another option would be for the ABCC, or the state itself, to sanction and distribute its own universal growlers. Theoretically, these generic glass jugs could be filled anywhere in the state and would require the consumer to keep track of what’s inside.

But even these methods raise concerns with local brewers. The sticker system leaves bartenders and breweries in charge of replacing the branding, which isn’t foolproof. And the fiscal requirements for issuing Mass.-branded growlers are unknown. What’s more, now-kosher blank growlers shed the very branding power brewers want to maintain.

Another solution was implemented by Bog Iron Brewing last winter: The Norton brewery “exchanges” a competing brewery’s growler for one of its own branded ones. Bog Iron would then recycle the old growler, and the consumer would still leave with a jug full of beer. Drinkers were thrilled with the program—one person exchanged 26 of their growlers on the first day. It’s a plausible solution to address branding concerns that, in this instance, pleased every party involved. Bone Up has since introduced a similar policy.

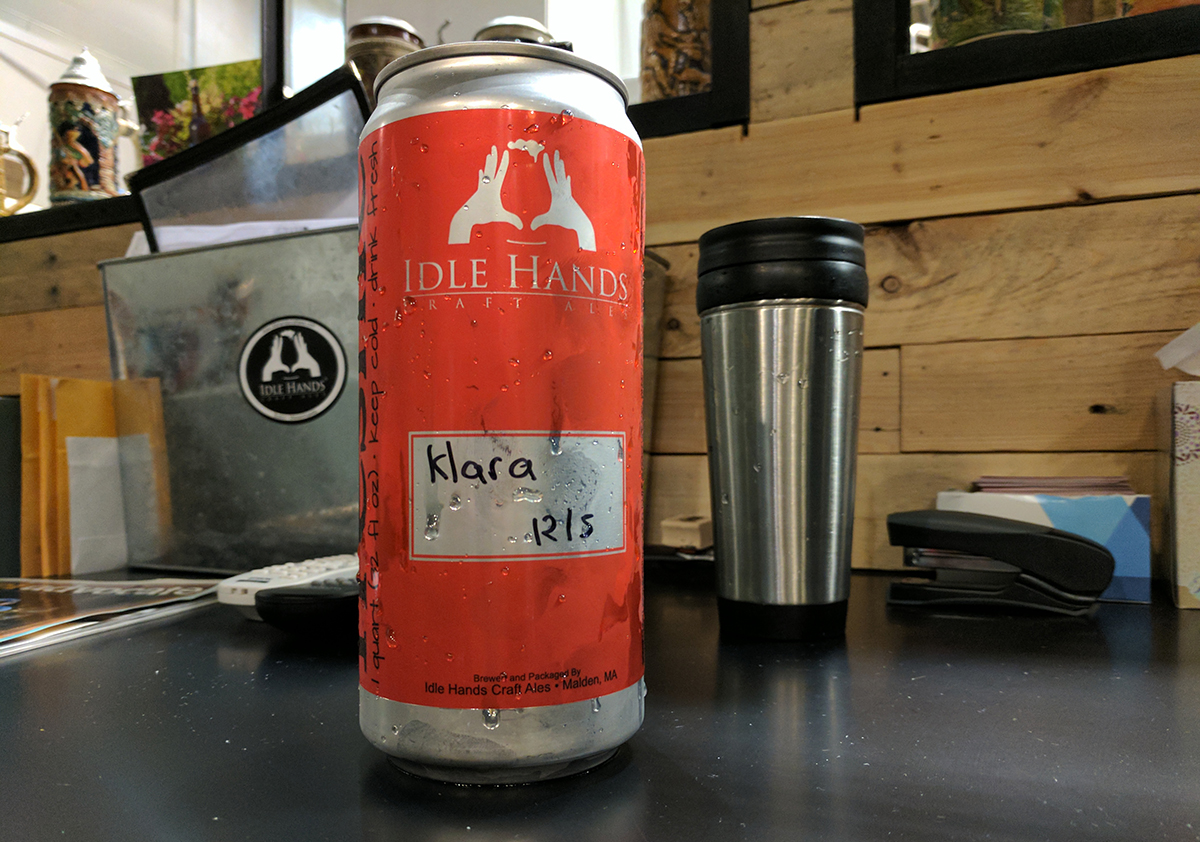

Idle Hands crowler photo provided

Crowlers Rising

But one alternative has separated itself from the pack: Crowlers. Essentially “canned growlers,” these 32-ounce tallboys are filled to order right from a tap like growlers, but are then machine-sealed.

Crowlers were popularized by Oskar Blues Brewing Company, the Colorado-based brewery credited with igniting the canned craft beer movement in 2002 with Dale’s Pale Ale. Alongside development partner Ball Corporation, Oskar Blues manufactures and distributes all the equipment necessary for breweries to fill their own branded crowlers, such as the canning machine and blank cans. Once a brewery buys all the associated tools, they can slap on their own labels and start filling tallboys.

All the benefits that make aluminum superior to glass also apply with crowlers, such as no light exposure and portability. The price difference is also minimal for consumers, with both glass and aluminum vessels costing around $10-$15 each to fill.

Crowlers are essentially the same as growlers, but drinkers can simply throw them in with other household recyclables, instead of bringing them back for a refill. A crowler-filling machine doesn’t take up much more room than a Keurig, leading locals breweries like Notch in Salem, Barrel House Z in Weymouth, and Aeronaut in Somerville, to just offer crowlers in place of growlers entirely.

The rise of the crowler over the past year has divided state brewers. Some favor growlers and all of their trailing failsafes, citing state regulations as a positive. Another group has jumped ship, instead favoring less restrictive alternatives like crowlers.

But the split isn’t even that simple. When it comes to growlers, cleanliness is also a huge variable. A dirty growler taints the beer, and brewers don’t want that uncertainty anywhere near their product.

That became a huge issue last fall in Malden, where Idle Hands Craft Ales is based. The brewery was told by the city that in order to conform with local health codes, it could only sell growlers if every single jug was deep-cleaned prior to filling it. Most breweries will wash a growler out before filling it, but the Idle Hands team wouldn’t have been able to fill growlers to order under Malden’s terms. Given the labor costs to clean growlers in bulk, and the strain on growler use already present statewide, owner Chris Tkach decided to take a hard pass.

“We were literally throwing [growlers] in the recycling bin,” Tkach said. “They’re no use to us now.”

His brewery’s solution was to switch to crowlers. Like the local breweries forced to adopt growlers from their inception, Tkach turned to crowlers to keep his to-go sales alive. He set up a rewards program to buy back growlers from consumers in exchange for crowler discounts, and began taking steps to help drinkers transition from glass to his brewery’s “freshies.” Idle Hands has since started canning a few of its core beers in 16-ounce four-packs, too.

“We’ll never bring [growlers] back. I don’t want to deal with them,” Tkach said. “And even if we did bring them back, I’m still beholden to the Malden health code laws. Even if I could fill a Night Shift growler, or Cambridge Brewing Company growler, it doesn’t solve my problem of having to clean and sanitize.”

Splitting the Tab

Crowlers aren’t a perfect solution, either. Night Shift’s Rob Burns argues that filling a crowler slows down bar service, and also says the container is still susceptible to oxidization. Like regular cans, crowlers also can’t be resealed and enjoyed another day, though Oskar Blues is working to address that issue with a new type of crowler.

It also takes a much bigger wad of cash to invest in a crowler machine and all of its subsequent equipment, compared to a few hundred glass growlers.

Is there a solution that benefits all parties, that allows consumers and brewers to coexist in this confounding, growler-ridden state?

“You’ll never see a 100 percent switch,” Tkach said. “The younger generation, who have adopted cans, see [crowlers] as a positive. It just requires a little more education for the older people that have always had this stigma about canned beer being bad, and not a quality product. They’re still married to their glass growler that they want to lug around.”

While there is something fulfilling about snagging draft-only offerings with a growler fill from a neighborhood brewery, the majority of customers find the current Massachusetts rules inconvenient. No matter the price point, nor how brewers feel, that fact will ultimately spur legislative action. It seems with the state’s recent attention on alcohol laws, that reality could be fast approaching. When that time comes, local brewers will have a decision to make.

“[Growlers aren’t] going to go away, but you’re going to see some breweries deciding which package they want to offer,” Tkach said. “It’ll be interesting to see how it all shakes out over the next few years.”