From Chowder Town To Culinary Capital

Acclaimed local toque Ming Tsai and Karen Akunowicz, this year’s James Beard Award winner for Best Chef: Northeast, on Boston’s journey from cream pies to crudo.

Part of Old Boston vs New Boston

Once upon a time, we were proud, insular, mean, gritty, corrupt, and great. But as Old Boston is washed away by a flood of rich, tech-savvy brainiacs and finance bros, we’re left asking: Are we losing the best or the worst parts of being Bostonian? And who are we becoming along the way?

Ming Tsai: We were known for really good seafood: Legal Sea Foods, No Name. But Boston was not even close to New York or San Francisco in an overabundance of high-quality restaurants. It was pretty plain Jane. When my parents would come visit me at Andover, they took us off-campus. We would either go to Chinatown for black beans and clams at Moon Villa, or we would just go to Quincy Market. Quincy Market was the catchall back then, in the late ’70s and early ’80s. It was like, Holy shit, this is so cool. Slices of pizza, fried dough, bowls of noodle soup: It was a melting pot of cuisine. I do remember a long time ago, I went to Locke-Ober with Dad on a rainy day. I think we were celebrating something. That was a to-be-seen restaurant back then, especially at lunch. Everyone was important; you could see by the way they walked and talked.

Karen Akunowicz: When you say Old Boston food, the thing that comes to mind is the idea that so much of the country has about us: clam chowder and baked beans and scrod. I think that’s a very antiquated vision of what Boston food means. When I hear it, I think of the restaurants that brought Boston dining onto a different level, whether you’re talking about Biba or Icarus, Hamersley’s or Rialto.

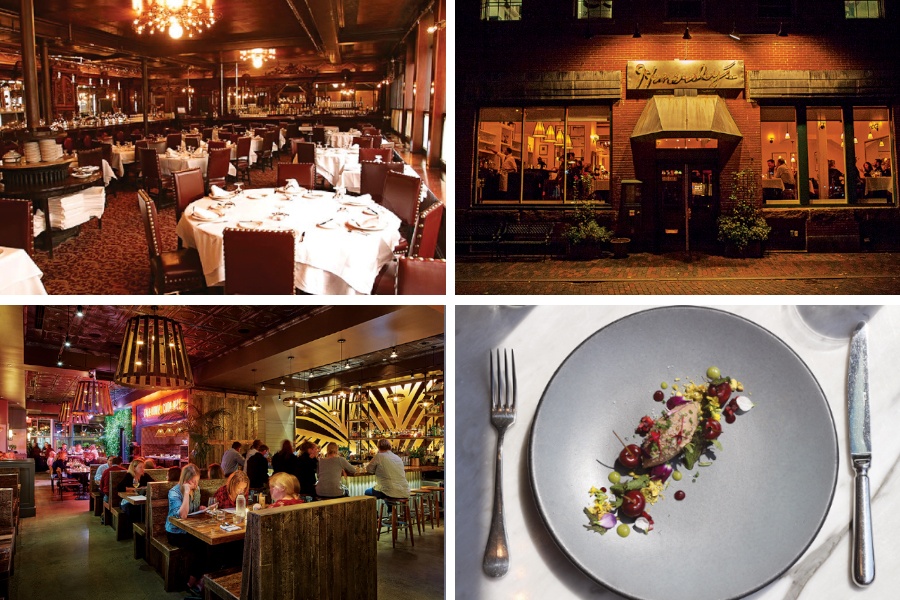

Scenes from a dining renaissance: clockwise from top left, Locke-Ober, Hamersley’s Bistro, Café ArtScience, and Tiger Mama. / Olga Khvan (Hamersley’s); Jared Kuzia (Tiger Mama); Photo courtesy of Locke-Ober/Facebook (LOCKE-OBER)

MT: Lydia Shire, Gordon Hamersley, Jasper White, Todd English—they were the first wave of very good chefs. They made people take notice. Lydia and Jasper just saw the opportunity. It’s the old adage: It’s easier to establish yourself as a big fish in a small pond. The reason I chose the Boston area was because it was not overbuilt yet with great restaurants. Now, I don’t even know half of the new chefs, to be honest. In the ’90s, keep in mind that the financial markets were going crazy. Everyone had cash, everyone was building restaurants. Boston was ripe for the picking. Michael Schlow came from New York to cook at Café Louis, and then opened Radius; Ken Oringer, who’s really my best chef friend, he came to Tosca, and then he decided to do Clio. In 1997, I called Todd English up and he was jamming busy. I asked him, “What do you think about opening up in Wellesley?” and he said, “You would kill it.” Any good restaurant, honestly, would have done well in the space I opened Blue Ginger. There was no competition and people were hungry, literally and figuratively, for something new.

KA: The other thing, when you’re talking Old Boston versus New Boston, is the areas people have been able to open amazingly successful restaurants. Look at the Fenway. There was nothing there. And Tiffani Faison and Kelly Walsh came in and not only created a vibrant restaurant in Sweet Cheeks, but also opened Tiger Mama. You look at someone like Joanne Chang, who 18 years ago had the vision to open Flour on Washington Street. Even 11 years ago, opening Myers + Chang, Christopher Myers and Joanne had no idea the growth that would happen.

MT: The challenge of the Seaport now is crazy expensive rent. It’s because the model has changed. It used to be for large office buildings and hotels, you could anchor those buildings with retail. With the birth of the Web and Amazon, though, everyone is buying online, and the only businesses that can anchor them now are restaurants. Even though they may pay for the build-out and give you a year’s free rent, once all those incentives go away, you still need to have X amount of revenue to have cash flow.

When you say Old Boston food, the thing that comes to mind is the idea that so much of the country has about us: clam chowder and baked beans and scrod. I think that’s a very antiquated vision of what Boston food means.

KA: When looking at a space for my new restaurant, I was reached out to about a spot in the Seaport. I could never have afforded the rent as an independent owner. It is very unfortunate that the only restaurants that can afford to go into those new spaces are large chain restaurants. It stunts the growth of the independent, chef-owned restaurants that Boston has always supported and rooted for.

In some ways, the party’s over; in others, it’s just getting started.

By Abby Bielagus

Where you discovered a new band then: T.T. the Bear’s, where the sound was lousy but your new favorite acts were literally within reach.Where you discover a new band now: The Sinclair, where the sound is exceptional but so is the security.Where you flirted then: On the dance floor at 15 Lansdowne, the glitzy predecessor to Studio 54 in New York.

Where you flirt now: Swipe right.Where you spent your babysitting money then: Allston Beat—even if you hadn’t saved up enough dough to buy anything, you could sit outside the Newbury storefront watching the cool

kids coming and going in their punk attire.

Where your kids spend their babysitting money now: Forever 21, Nordstrom Rack, or any of the other corporate monoliths now taking over the street.

Where you got high then: In the bleachers at Fenway, where the potent combo of hot dogs loaded with onions and cigarettes provided a strong cover for the smell of weed.

Where you get high now: Literally anywhere. It’s legalized, baby.

Where you sobered up then: Bova’s Bakery, which served pizza, calzones, and subs to the hopelessly over-served—perfect for soaking up beer before bed.

Where you sober up now: Bova’s Bakery. Thank God.

MT: The biggest challenge in New Boston, though, that no one can resolve is staff. There’s such a void of good cooks, waiters, and bartenders because there are so many more restaurants being built. We’re all fighting for the same staff; we’re all training the same people. It’s not going away, this problem, and it’s going to self-correct.

KA: Staff aren’t making enough money, so they move to another city where the cost of living is less. I don’t see it changing. It will force us in a good way to do better with paying people more money and creating better work environments. Which is hard. Restaurants run on such a tight margin. I wish I had a magic answer for it. On the other hand, I think Boston tends to be ahead in terms of how many female chefs, female restaurant owners we have here. I have always had strong female role models to look up to. You look at Lydia Shire, Jody Adams, Barbara Lynch, Joanne Chang, Ana Sortun. These are women who have always stood out not only as contributing to the dining scene, but also creating it.

—As told to Brittany Jasnoff

Interviews have been condensed and edited for clarity.