The Year That Changed Boston’s Dining Scene Forever

All of the takeout in the world isn’t going to save your favorite restaurant. Where does that leave Boston? With the chance to rethink, rebuild, and make our food scene even better than before.

Photo via Sitaade/Getty Images

What would you choose for a last meal?

I never thought I’d ask myself that question—or a version of it, anyway—until a microscopic virus arrived in Boston last winter and completely upended life as we know it. As offices big and small quickly began shutting down in early March, my food-editor brain immediately began thinking, as it is trained to do, about what this would all mean for local restaurants. If places of business couldn’t operate, surely dining rooms, where crowds (wonderful crowds!) gather to be close together, to shake hands and give hugs and share food, would be next.

That scared me. Because if there’s one thing I’ve learned from chefs over the past dozen years of writing about them, it’s that restaurants are an increasingly tough business with super-slim profit margins. However well they may hide it, small mom-and-pop operations and buzzy hot spots alike typically have only a few rainy-day dollars in the kitty. Could any of them hope to survive this storm?

And so, just days before Governor Charlie Baker issued a temporary ban on dining at restaurants that ultimately lasted until June, I decided to enjoy one last meal at Sarma in Somerville. Pulling aside a velvety curtain at the door and stepping into the jewel-toned dining room, I grabbed a solo seat at the bar, ordered up a splay of chef Cassie Piuma’s spice-bomb Mediterranean small plates, and sipped a couple of cocktails while eavesdropping on the thirtysomething couple canoodling next to me. Sarma has the kind of uniquely urban energy that I wanted to soak up like a sponge—just in case it might be a while before I felt it again.

Lo and behold, even as I write this half a year later, that energy is still at an unprecedented lull. Sure, Sarma is chugging along, albeit only in takeout and patio-seating form, like many of the other restaurants that have yet to reopen their dining rooms due to COVID-related caution, capacity limits that make doing so financially pointless, or both. Relatively speaking, though, Sarma is actually one of the lucky ones—because by fall, nearly one in four restaurants in the Bay State had closed, according to the Massachusetts Restaurant Association, putting more than 200,000 people out of work and jeopardizing an entire industry that is the backbone of small business (one in 10 Massachusetts workers is employed by restaurants) and makes incalculable contributions to local culture.

With winter coming, the situation will get worse before it gets better, according to just about everyone I’ve spoken to in the restaurant world. Why? Because it’s become abundantly clear to most operators that diners are still not rushing to return inside—a big problem when outdoor seating, a stopgap at best, is becoming increasingly impractical. Meanwhile, with intransigent landlords continuing to demand the kind of high-priced commercial rents that made Boston nearly unaffordable for most restaurants even in the before-times, all of the takeout in the world can’t offer much more than life support. Without significant outside aid, some industry experts expect that as many as 40 percent of independently owned Boston restaurants could fold before the thaw arrives.

And yet, in the wreckage that remains, Boston’s dining world may still find an opportunity to seize, at least according to the more optimistic folks out there. I know that most people are sick of hearing about the power of “pivoting!” But we must face up to the inescapable fact that, even if Uncle Sam eventually comes galloping in with a big, fat industry-bailout check, a lot of restaurants still won’t make it, and many of the survivors won’t look the same.

After all, if restaurants have always been this close to circling the drain, maybe something had to change anyway, says Ed Doyle, a former longtime chef whose Boston-based hospitality consulting company, RealFood, is now counseling eateries through the COVID crisis. “Many restaurants were a bad snowstorm away from this condition already,” says Doyle, who thinks the pandemic has only accelerated the imperative to grapple with a reality that was easier to ignore before.

In other words, restaurants might be able to do exactly what the rest of us have been doing during this strange time: step back, take stock, reconsider old habits, and try some new things. For you or me, maybe that meant debuting a new hairstyle or calling a divorce lawyer—for restaurants, that might mean selling cook-at-home meal kits or doing away with gratuity-based wages that keep staffers living hand to mouth. “My hope is that, coming out of COVID, we’re going to work smarter—not harder,” Doyle says.

In order to take advantage of whatever bittersweet silver lining exists, though, a few things will have to happen. Chefs will need to sustain the camaraderie they have forged while fighting for their livelihoods, come up with even more innovative ways to entice visitors, and make social responsibility a key ingredient of their business—not just because it’s the right thing to do (although that should be enough), but because customers are thinking more carefully than ever about where to spend their money and what kinds of values they want to support.

As for us diners? We’ll wind up wielding unprecedented power over what restaurants remain and, most important, what kind of Boston we become as a result: a sea of bland national brands with pockets deep enough to persevere, or a garden of locally grown delights that will actually preserve our unique neighborhoods and colorful communities. In the wake of COVID-19, saving our restaurants will go hand in hand with saving our city.

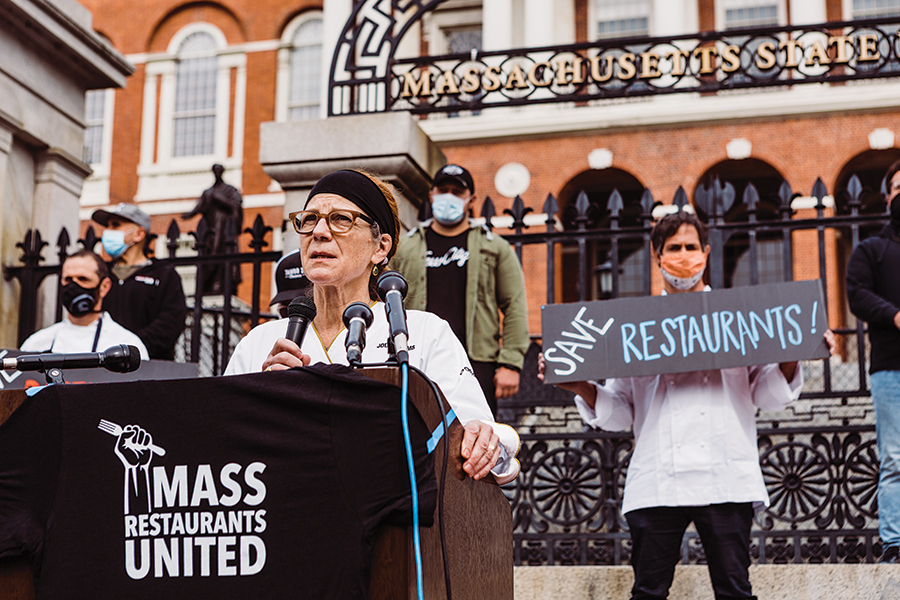

James Beard award-winning chef Jody Adams, cofounder of the advocacy group Mass Restaurants United, calls for industry relief on the steps of the Massachusetts State House. / Photo by Janice Checchio

It’s a windy afternoon in Boston—the first day of fall—and a dozen or so figures are standing 6 feet apart on the Massachusetts State House steps, wearing COVID-thwarting facemasks and holding handmade signs. One by one, they take turns behind a podium to passionately share their stories and plead their cases to TV-camera-toting reporters. At first glance, it’s not that unusual a sight in this incendiary election year, one that’s been marked by major protests and energized social movements in cities across the country.

But if there’s such a thing as a typical activist in 2020, well, these restaurant folks don’t look like it. For starters, they are wearing white chef coats and kitchen aprons. And their signs don’t say, “Resist,” “Defund the Police,” or any of the other rallying cries commonly seen in recent months—instead, they implore, “Save Restaurants.”

You see, these are the leaders of the grassroots coalition Mass Restaurants United, among them well-known local chefs Jody Adams, Tony Maws, and Ken Oringer, all James Beard award winners. Without significant financial relief from Beacon Hill, these industry advocates argue, the coming winter will finish the extinction event that started in the spring. “It’s getting colder, and people aren’t willing to go inside,” Stephanie Burke, owner of the Mexican restaurant Lenny’s Hideaway, tells the crowd through her microphone. The threat is clear: “We are up against Mother Nature.”

What are they asking for? To begin with, the passage of a Massachusetts economic development bill that includes a relief fund for restaurants; it would issue grants to help cover rent, payroll, and insurance, among other expenses, as well as cap the restaurant-gouging fees—sometimes as much as 40 percent an order—that are charged by third-party food delivery services such as Postmates and Uber Eats. Beyond Beacon Hill, Mass Restaurants United also works with the national Independent Restaurant Coalition, which formed during the pandemic to lobby for a $120 billion federal aid package that specifically supports small-scale operators. That legislation continues to languish in Congress long after bailouts went to airlines, fossil fuel companies, and other industries with more influence in DC than the IRC’s cooks turned crusaders.

Any forthcoming federal and local relief will prove invaluable to folks like Oringer, who says sales at JK Food Group—the portfolio of eateries (including Toro, Coppa, and Little Donkey) he owns with fellow Beard winner Jamie Bissonnette—are down 50 percent compared to last year. “We’re not going to be making a dime this whole year,” he tells me. In March, the duo made the hard decision to close the seven-year-old Manhattan location of Toro to focus on the Boston original; they knew they wouldn’t be able to save both. “We’re clawing for everything we can get,” Oringer says.

The situation is even more dire for local eateries owned by people of color. It’s well documented that Black restaurant owners face deep-rooted inequities that make it significantly more difficult for them to access startup capital and credit even in good times. “We’ve been underbanked and under-resourced,” says Nia Grace, whose South End restaurant and live-music venue, Darryl’s Corner Bar & Kitchen, is one of only eight Black-owned eateries that hold an exorbitantly expensive Boston liquor license. “You have certain systemic issues that have kept us in a certain space.” Just look at the disparities that exist with regard to pandemic relief: Restaurant Business reports that only about 130 of the 49,000 U.S. restaurant companies that received federal Paycheck Protection Program loans were Black-owned.

Nia Grace, cofounder of the Boston Black Hospitality Coalition, at her restaurant Darryl’s Corner Bar & Kitchen. / Photo by Matt Kalinowski

These challenges explain why Grace formed the Boston Black Hospitality Coalition this summer. So far the coalition of Black-owned restaurants and bars has spearheaded an inaugural Boston Black Restaurant Month promotion, launched a beer garden in Nubian Square, and raised $80,000 to date in relief funds for member businesses, among other efforts. “We’re trying to look at the granular details that are going to make a difference in our industry going forward,” Grace says of her coalition’s work. “I don’t think we have all the answers, but we’re heading in the right direction.”

It’s important that they keep looking for them: After all, if we don’t make a concerted effort to prioritize the recovery of POC-owned restaurants, vast swaths of Boston will suffer. Ours is one of the most racially segregated metro areas in America, according to U.S. Census data; what would happen to neighborhoods such as Roxbury, where 83 percent of the businesses in the Boston Black Hospitality Coalition are located, if a large number of eateries there shuttered?

We’ve already seen the result in restaurant-heavy Chinatown, where a thinned-out downtown office population has killed the vital lunchtime business and empty nightclubs no longer attract midnight-munchies crowds. Add a hefty dash of racism, fanned in large part by a commander in chief screaming “China virus!” all over the dial, and it’s no wonder that the neighborhood was slammed early and hard by restaurant closures. “We are getting hit from every side,” says Brian Moy, who owns neighborhood hot spots Shōjō, Ruckus Noodle Bar, and China Pearl. The restaurateur has been working in the kitchen of the family-run China Pearl since even before he was 10 years old—but says that hasn’t stopped him from hearing “Go back to China” during the pandemic.

As a Chinatown-area representative to Mass Restaurants United, Moy has worked hard to help his neighborhood weather the storm. In the aftermath of March’s shutdown he launched Chinatown Delivers, a service that ushered food from China Pearl and a couple of other neighboring eateries to the suburbs. It was successful, proving there’s potential in innovative, collaborative takeout projects. Ultimately, though, Moy didn’t have the time or resources to run it while doing everything else he needed to do to keep his restaurants afloat.

And that brings us back to winter, which Moy is dreading: Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s Eve, and Chinese New Year are typically the busiest nights in the neighborhood. This season, he knows, will be very different. “The energy,” Moy says, “is nonexistent.”

On her first night of takeout service, Jen Royle was in tears in her kitchen—which is not how you would expect to find Jen Royle, if you know anything about her. The former Boston sportscaster, who owns Table in the North End, has a salty sense of humor, boldly competed as a self-taught chef on ABC’s The Taste, and is known for her bark on Twitter: She’s not afraid to alienate any of her 31,000 followers by cursing out Donald Trump or putting rude customers in their place. It’s what her fans find endearing and her haters, well, hate.

But on this evening, Royle was in full-blown meltdown mode. Her intimate restaurant, where groups of strangers typically gather around a single table, passing her chef’s-choice plates hand to hand, was exactly wrong for social distancing. So now the self-described “rookie” was drowning in a sea of stress and scampi sauce as she tried to run an à la carte takeout operation. “I kicked a pan across the room,” Royle recalls. “I was crying. I said, ‘I don’t know how to cook like this and I’m not ashamed to say it.’”

Luckily, someone on her tiny kitchen team snapped her back to the task at

hand: “She said, ‘Listen to me. We’re fucking going to do this. Why? Because we have no choice.’”

No choice. Royle got her head in the game and since then, she’s managed to keep her revenue at pre-pandemic levels. How? Flexibility, she says. Right now, her restaurant serves eight-course, family-style, fixed-price feasts twice nightly on site; offers limited à la carte options for walk-ins only; cranks out takeout; and is available for private, chef-hosted dinner parties. She’s also about to open Table Mercato in a neighboring storefront, where she’ll sell stuffed peppers, marinated artichokes, and other house-made Italian provisions, as well as artisanal kitchen sundries. She never wanted this challenge, but she’s nothing if not determined to crush it: “I became a better chef by learning how to do things on the fucking fly.”

Royle is not totally alone. I’ve talked to some restaurant owners who tell me that they’re doing okay, or that they’ve implemented new ideas they’ll continue post-COVID. A few have even bested last year’s same-day sales. They don’t want anyone to know. They feel bad. They are aware that they are very much the exception to the rule.

Yes, tough days lay ahead. But having established the desperate state of the dining world and the dire need for the government to swoop in and save small businesses, jobs, and a crucial component of city culture, it’s also important that we scan for signs of life, so that we can learn what works and how restaurants may look going forward. “Anyone who says this is the death of the restaurant industry is not paying attention,” says RealFood’s Ed Doyle. He believes that the industry is instead changing form, and those who survive must be willing to change with it. “The old normal is never going to be there again. For better or worse, when we come out of this it’s going to be a whole new food and beverage landscape.”

What will that landscape look like? No one knows for sure, but experts like Doyle suspect that from now on, traditional onsite dining will be just one tool in a whole Swiss Army knife of services. Restaurants may become more multifaceted touchpoints of food and community, diversifying their services and the ways they make money.

Some restaurants, in fact, are already making pivots that could continue even after a vaccine becomes available: There’s the experiential dining at Shiso Kitchen in Somerville, where customers can book themed feasts accompanied by a class from chef Jessica Roy. Over in the Fenway, you can now reserve an intimate evening with one of Boston’s biggest chefs, Chopped judge Tiffani Faison, at Fool’s Errand, her pint-size bar that has otherwise been repurposed as a pop-up shop selling wine and goodies from her restaurants. Other small eateries have started exploring creative partnerships to pool resources: When Somerville’s old-school Sligo Pub couldn’t reopen without food, it transformed a shared parking lot into a pizza-and-suds patio with neighbor Dragon Pizza.

Even takeout is getting more innovative and interactive in a way that could open up opportunities in the future. For instance, the fine-dining destination Tasting Counter now offers take-home meal kits with everything “guests” need to participate in virtual cook-along classes. Restaurants are also packing up fresh produce, artisanal goods, and their own signature groceries along with their customers’ to-go orders, offering convenient access to small farms and food purveyors they wouldn’t get otherwise. (Come for the tacos, leave with a CSA share!) Doyle even expects to see more takeout-only outfits based out of shared commercial food-prep facilities, a.k.a. “cloud kitchens.”

Eventually, how you get that food may change, too. Doyle points to emerging technologies such as climate-controlled lockers where customers scan barcodes to pick up chef-prepared plates, as well as machines vending high-end snacks. Restaurants may also start investing in self-operated delivery, to cut out those crucifying third-party fees. Emerging platforms connecting restaurants directly to drivers will make this easier—and anyway, delivery doesn’t have to start with a fleet of trucks. Orders placed to chef Will Gilson’s new, multicomponent Cambridge restaurant the Lexington, for instance, will be walked over to neighboring condo buildings, like room service.

Many of these still-nascent ideas sound purely transactional, but restaurants can still—must still—get hospitality’s human touch across. Living out values that care for the community, not just individual customers, is one way to do that. For proof, look to Tracy Chang of Cambridge’s Pagu. In the early days of the pandemic, she and Oringer cofounded Off Their Plate, a now-national initiative that coordinates with hospitals to feed frontline healthcare workers. Alongside Irene Li, chef-owner of Mei Mei, Chang also helped to launch Project Restore Us, which provides “contact-free, culturally appropriate grocery delivery to working immigrant families in Boston’s most vulnerable neighborhoods.” These initiatives were not designed to be massive moneymakers. But they’re one more way to generate some revenue, keep more restaurant workers employed, and serve the city. “Restaurants, my own included, have to reevaluate their business models,” Chang says. “Some restaurant owners don’t want to become something else, and maybe they’ll close as a result. Others who are willing may survive this pandemic and be viable.”

While Chang is packaging grocery orders at Pagu, Kendall Square biotechs only a few blocks away are working on vaccines for the coronavirus, the invisible enemy that started this mess. Maybe there’ll be one soon, and we’ll be back to normal before you know it. But more likely, I think that it will take time, testing, and trial by error to find the right fixes for a dining world in crisis. The frustrations will be many; the casualties, sadly, too. But we’ll keep looking. Our city life depends on it.