Here’s the Latest Teaching Method Inspiring Independent School Students

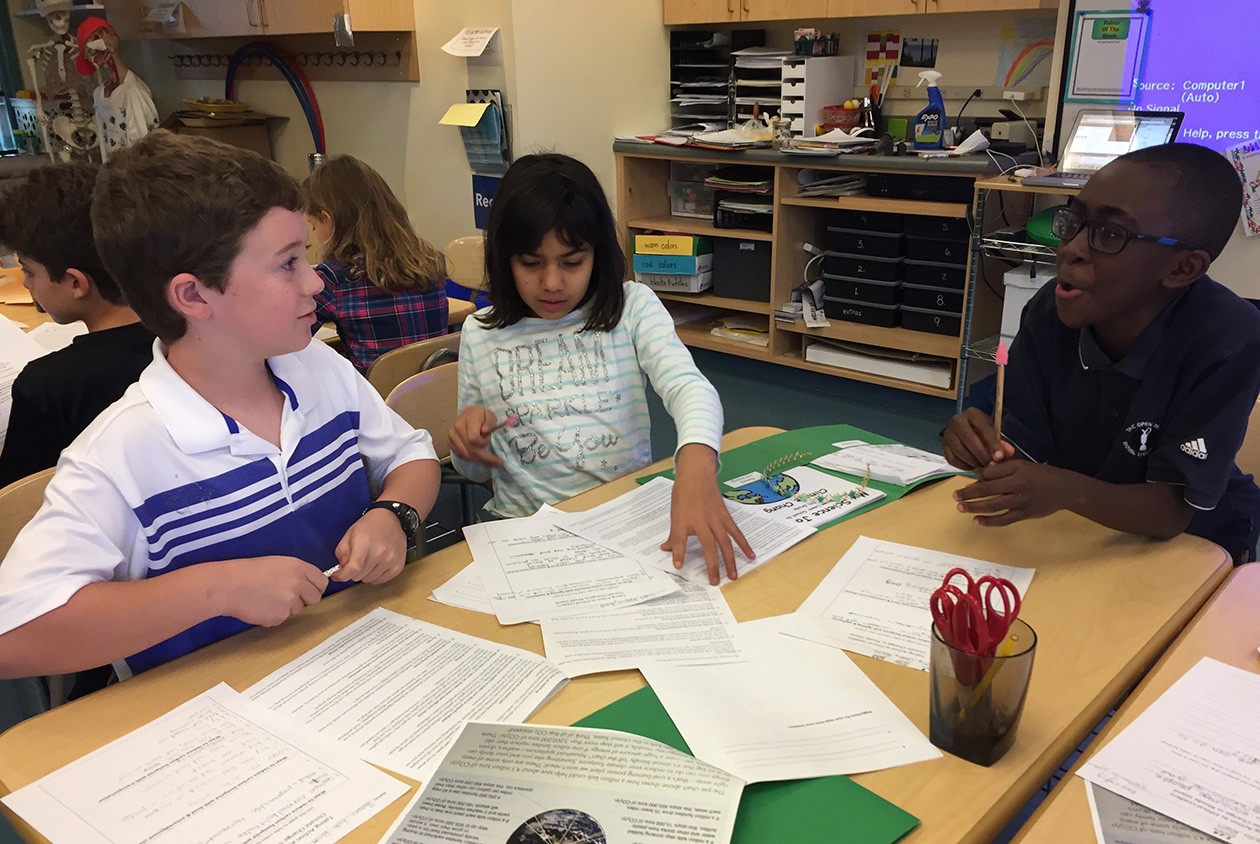

Photo credit: Moses Brown School

Does your child seem interested in his or her homework? Do they care about the work they’re doing in the classroom? Do you even know what they’re working on?

It’s hard to keep kids’ attention. That’s why some independent schools like Moses Brown School in Providence, Rhode Island are employing project-based learning to engage students in their work. When your child is focused on answering a specific question, they pay more attention and tend to retain more information.

“Project-based learning is contextualized in a problem—often called the ‘driving question’—that needs a solution,” says Elizabeth Grumbach, a teacher at Moses Brown School. She and her fellow teachers have used this methodology to offer engaging units of study that ask these kinds of questions:

- How can we support the right whales who are struggling to survive off the New England coast?

- What can we do, as fifth graders, to address the impacts of climate change happening in our state?

- What innovations could we suggest to reduce the religious intolerance expressed in our region?

- How can we use what we learn from reading Antigone to help fourth graders understand the ways conversations can become conflicts and how these conflicts can be resolved?

- How would you tell the story of the American Revolution if you had a single day in Boston?

- How can we use baking soda and vinegar to power a boat constructed from recycled materials?

- How can we advance engaged scholarship and social innovation through community partnerships?

Photo credit: Moses Brown School

For all units, the bulk of the work is not learning the baseline material but rather coming up with solutions and the best formats to use, taking into account both the scope of the problem and the potential solution. For some problems, such as climate change, the solution was advocacy for legislatures or agencies.

Other projects lend themselves to more ambitious final deliverables. After learning about different religions and deciding the best way to foster religious tolerance was to build an interfaith center, the elementary class studying this unit was tasked with designing a 3D prototype of the building. When the seventh-grade American history class was asked to come up with the best tour on the American Revolution, success was judged in part by how well they took into account practical considerations such as the locations of the restrooms along the route. For ninth grade immersion, students engaged in design thinking alongside community partners to solve an authentic problem specific to the local organization in a week.

The advantage to this approach in our modern world is clear. “Our students are now gaining regular, extended practice working on diverse teams to answer big, open-ended questions,” says head of school Matt Glendinning. “These are the kind of questions that don’t have a simple or black-and-white answer.”

For more information about independent schools in New England, visit aisne.org or search our Find It database.

This is a paid partnership between Association of Independent Schools in New England and Boston Magazine