MGH Investigates: How Does the Body Respond to Tumor Growth?

Photo Credit: Mass General Cancer Center

Cancer researchers and physicians have long been studying the ways in which cancer grows and spreads; what drugs or therapies might thwart that growth, and how can they “outsmart” the cancer, but what causes cancer to grow and metastasize is still not well understood by scientists.

Conventional wisdom has long held that any tumor cell remaining in the body could potentially reignite the disease. Current treatments therefore focus on killing the greatest number of cancer cells. Successes with this approach are still very much hit-or-miss, however, and for patients with advanced cases of the most common solid-tumor malignancies, the prognosis remains poor. So now what?

A recent study, published in Scientific Reports on Feb. 19, was conducted by researchers funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), looked at what might be unique about the tumor “microenvironment” that may play a role in the growth or lack thereof, of tumor cells.

Cancers are heterogeneous tissues comprised of multiple components, including tumor cells and microenvironment cells. The tumor microenvironment has a critical role in tumor progression. And is comprised of various cell types, including fibroblasts, macrophages and immune cells, as well as extracellular matrix and various cytokines and growth factors. Fibroblasts are the predominant cell type in the tumor microenvironment. They frequently promote cancer progression by inducing cell proliferation, inflammation, blood-vessel growth and metastasis.

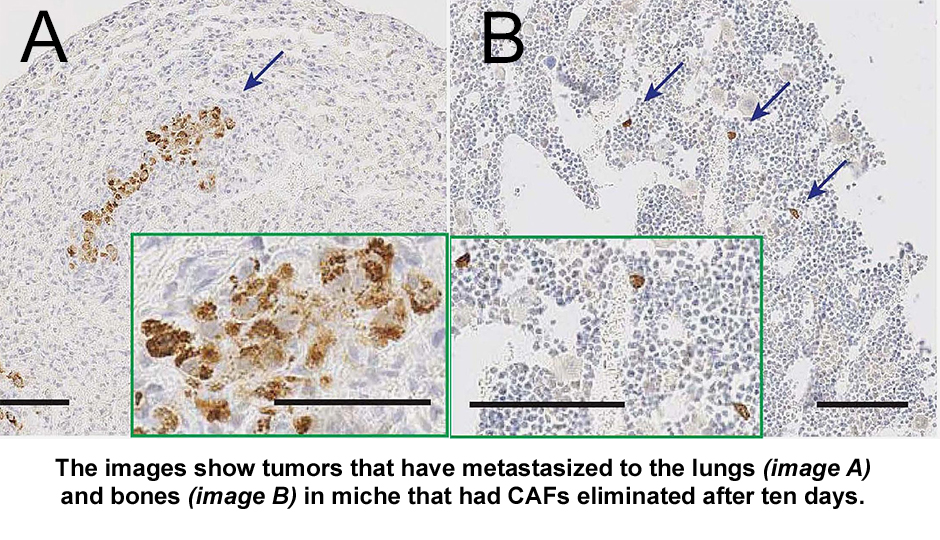

Biju Parekkadan, Ph.D., assistant professor of surgery and bioengineering at Mass General, and his team designed an experiment with the goal of better understanding the cellular environment in which tumors exist (called tumor microenvironment or TME), and the role of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in tumor growth. In an effort to understand whether targeting CAFs could limit the growth of breast cancer tumors implanted in mice, they bioengineered CAFs with a genetic “kill switch.” The cells were designed to die when exposed to a compound that was not toxic to the surrounding cells.

The unexpected results were mixed. There was no impact on cancer spreading if the CAFs were killed early on. If the CAFs were killed a week later, there was an increase in metastasis in the mice. What this means is that it is important to fully investigate the dynamics of the tumor microenvironment and the timing of intervention in cancer treatment.

More research will reveal whether or not there is a scientific basis for targeting CAFs for destruction, and if so, what is the optimal timing of the intervention so that the cancer does not spread. it is important to understand that most cancer deaths result from metastases to vital organs rather than from the direct effects of the primary tumor.

It is exciting to think there may be some pieces to the puzzle; found in the understanding of the way the body responds to a developing tumor may be as important as understanding the way the tumor acts all by itself.

This is a paid partnership between Mass General Cancer Center and Boston Magazine